This substantial brick house in Edenton, North Carolina, has an unusually fine veranda with an octagonal extension on the right, balanced on the left by a three-story octagonal tower.

If you had to pick just one architectural style to represent the American Victorian house, you could do a lot worse than the Queen Anne. There were plenty of other house styles around in the Victorian age—which was, if nothing else, a period of rampant architectural enthusiasms. After the Civil War, American homebuilders, eager to get their architectural bearings, tramped, metaphorically speaking, through centuries of European history, finding noteworthy relics everywhere they looked. Italianate, Gothic Revival, Second Empire, Stick, Eastlake, Romanesque Revival, even Moorish and Egyptian Revival styles, all had their champions.

Yet it was the American Queen Anne, a ubiquitous symbol of prosperity, community, and family in the late 19th century, that won the heart of the nation. It popped up everywhere, in countless shapes, sizes, and combinations of building materials and decorative elements, in cities, suburbs, and rural areas. The Queen Anne style might be viewed as a reaction against the rather gloomy aspect of Gothic architecture on the one hand and the rigid formality of, say, the Second Empire mansard house on the other.

Mock Medievals

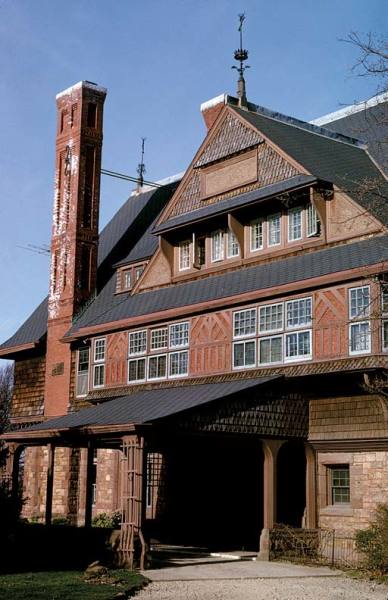

H.H. Richardson’s 1874 Watts-Sherman House in Newport, Rhode Island, started the American Queen Anne craze.

Queen Anne herself, ruler of Great Britain and Ireland from 1701 to 1714, would surely have been astonished had she lived to see how 19th-century America transformed the red-brick and half-timbered buildings of her era. Taking a cue from Richard Norman Shaw, Philip Webb, E.W. Godwin, and other mid-19th-century English architects who turned away from 18th-century classicism to revive earlier, post-medieval forms, American architects produced a scattered array of freewheeling Queen Anne-style buildings. The first and most famous of these was H.H. Richardson’s wonderful Watts-Sherman House in Newport, Rhode Island (1874). With its broad, high gables and expansive, multipaned casement windows, Richardson’s design suggested, without mimicking, houses of the actual Queen Anne period.

The informal, irregular massing of early Queen Anne-style houses evoked the haphazard construction history of late-medieval buildings. Inevitably, as the style was adopted by less talented architects and less wealthy owners, its outlines blurred into the comfortably asymmetrical, picturesque amalgam of gables, verandahs, steep roofs, bays, and turrets that we see in so many houses built between about 1880 and 1900.

In the same way, the choice of building materials changed. In the beginning, the hallmark of the Queen Anne house was masonry, particularly brick and half-timbering, with elaborate decorative stone accents. Over time, the importance of some of these elements faded, and even wooden houses laid claim to a Queen Anne heritage. They only had to boast irregular massing—preferably with an assortment of rooflines, maybe a turret or two, a few tall, corbel-capped brick chimneys, and possibly some heavy, carved ornament decorating the many gabled dormers and bays. The carved stone of earlier years was often replaced by wooden spindlework, courtesy of new machine-driven lathes and a seemingly endless supply of wood from the hitherto-untapped forests of the American heartland. Building materials were easy to come by—either close at hand or within reach by means of the nation’s rapidly developing railroad system.

Known as the “Eyebrow Dormer House,” this handsome Queen Anne with a distinctive three-story bay window at the left is in the small central Florida town of Lake Helen.

New printing technology and an advanced postal system also contributed to the spread of the Queen Anne style. It was given impetus on this side of the Atlantic by widely circulated planbooks from architects such as Henry Hudson Holly of New York, who published Modern Dwellings in Town and Country in 1876, including with his house plans a great deal of detailed advice about furnishing and painting them. The Connecticut firm of George and Charles Palliser (New Cottage Homes, published in 1887) similarly offered floor plans and elevations of Queen Anne houses and other buildings in their illustrated catalogs. George F. Barber established a booming architecture-by-mail business in Knoxville, Tennessee, furnishing both custom and stock designs to well-heeled clients all over the country. Many Barber houses survive today—there’s probably at least one in a neighborhood near you—and many are so distinctive (some might say bizarre) that they are easily recognized by Barber aficionados. The earlier ones are quintessentially Queen Anne, with round wooden turrets and many gables.

Other noted architects producing Queen Anne designs included Samuel and Joseph Newsom of San Francisco, Peabody and Stearns of Boston, Bruce Price of New York, and G.W. and W.D. Hewitt of Philadelphia.

A great part of the appeal of the Queen Anne style lay in its versatility—the ease with which it could be adapted to houses of any size, from cottages to mansions, for families with incomes that ranged from decidedly moderate to exceptionally lavish. Queen Anne was as useful for narrow city row houses as it was for sprawling suburban mansions.

This Barber Queen Anne in Edenton, North Carolina, built in 1897, is handsomely designed and well-proportioned, with a notable veranda and another three-story octagonal tower.

Added to this, there was also the appeal of the style’s ability to serve the changing needs of the 19th-century family. Interior spaces often included generous tiled entry halls, prominent wooden staircases, paneled walls of oak and chestnut, inviting inglenook fireplaces with glazed decorative tiles, dining rooms with stained-glass windows and built-in china cabinets, modern kitchens with cast-iron cookstoves, hot and cold running water and convenient backstairs, fully plumbed bathrooms, and often, central heating systems.

On the exterior, big wraparound verandahs—not stiffly formal classical porticos—served as gracious extensions of the interior rooms, providing fine outdoor sitting rooms when the weather was clement and entrances sheltered from rain or snow when it wasn’t. Smaller entrance and service porches were both decorative and useful.

Embellish to the Max

This spectacular 1893 tour-de-force by George Barber in Mount Dora, Florida, could hardly sport more ornament even if the architect had tried.

Although there was an enormous fondness for diamond-paned casements and stained-glass windows, these were a far cry from their tiny medieval predecessors. Not only were they used in quantity, they were often impressively large. In many double-hung windows, small clear-glass panes (frequently in groups of 20 or more) formed the upper sash, while the lower sash held a single large pane, made possible by advanced glass-making machinery. They were used as well in myriad bays and oriels that adorned the Queen Anne house. Thus, the Victorian demand for light and air was served all through the house without sacrificing an ounce of stylishness. Even dormer windows in attics and upper storeys were not mere practicalities but further opportunities for ornamental expression.

Exterior doors were major statements of taste and prosperity. Of heavy paneled wood with gleaming hardware, these were designed to impress both visitors and passersby. Inside, versatile pocket doors might slide into the walls to turn two small rooms into one, or be closed to form more intimate spaces. Alternatively, spindlework screens might suggest a division between rooms or set off a stair hall from an entry hall.

This house on Maple Street—Madison, New Jersey’s premier Victorian street—is a straightforward design with a fine front porch.

The post-Civil War years were the golden age of elaborate cast-iron ornament, and the Queen Anne house provided plenty of excuses to use iron furbelows, from front-yard fences to rooftop cresting. In fact, this was a style that never faltered in the face of potential decorative meltdown. Half-timbering in gables and upper stories; multicolored, variously shaped slate or wooden shingles on rooftops and dormer roofs, shoulders, and faces; walls laid up in patterns of varicolored brick—oh, it may have been much too much, but it was so gloriously Victorian!

And should such natural materials prove too pallid for the homeowner’s taste, there was always paint to enhance the effect. Henry Hudson Holly solemnly recommended a five-color palette (including buff, dark green, red, black, and a brilliant blue) for a recessed doorway—and then, of course, there would still be the windows and other trim to be dealt with.

With its emphasis on warmth, informality, and human scale, the Queen Anne house was a nearly perfect expression of the optimistic exuberance of Victorian America. As with all such youthful fantasies, though, there came a time when it really was too much, when the calmer lines of the up-and-coming Colonial Revival style seemed to make more sense. By about 1900, the Queen Anne’s day was clearly ending. Yet its legacy surrounds us, brightening city streetfronts and old suburban neighborhoods with its slightly zany, anything-is-possible confidence.