Driving north through Wisconsin last summer, I passed six A-frames along the side of the road. One served as the lobby to a rather rundown motel, another was a small suburban church, and the rest stood as dwellings peeking out from the pine forests. All were at least 30 years old. These structures were the enduring evidence of the post-World War II boom in modest and affordable A-frame house construction—a triangular building form so influential that its cultural cach was co-opted for other uses, such as motels and churches. Where did these odd buildings come from and what made them so popular during the 1950s and ’60s?

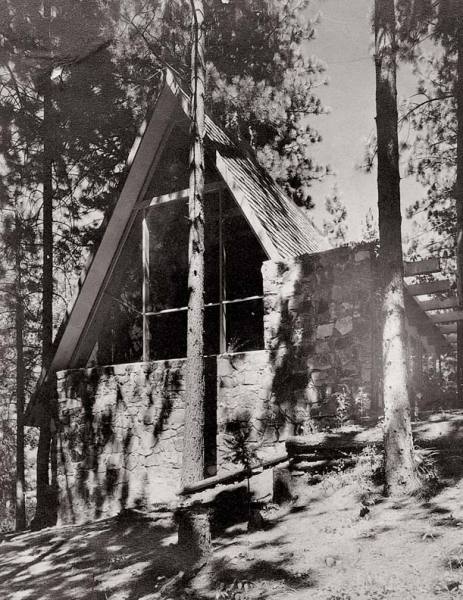

The Sierra Club was an early adopter of the A-frame. The Bradley Hut was dismantled in 1997 and reconstructed four miles from its original site.

Dick Simpson/Princeton Architectural Press

The A-frame was the right shape at the right time. The mid-20th century was the era of the second everything, when postwar prosperity made second televisions, second bathrooms, and second cars the just desserts of middle-class American life. Signs at hardware stores and ads in popular magazines took the idea to the next step, declaring, “Every family needs two homes!…one for the work-week, one for pure pleasure.” Increases in disposable income and free time, new cost-saving building materials, cheap credit, and road construction that turned wilderness into affordable recreation lots were democratizing the vacation home.

Many of these homes were based upon forms traditional to wilderness settings, from log cabins to clapboarded cottages. At the opposite end of the spectrum were high-concept houses: modernist boxes with flat roofs and glass facades, standing defiant against the landscape. Yet for vacationers who wanted a getaway that was innovative and exciting, modern yet warm, a place wholly suited to the informality of the new leisure lifestyle, a third alternative emerged.

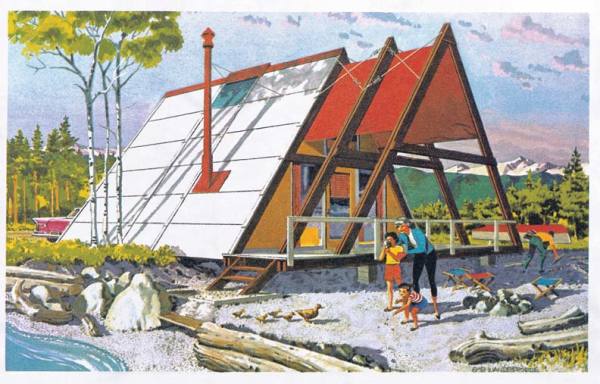

Plan-book A-frames like the Ranger from the Douglas Fir Plywood Association cannily promoted both a lifestyle and a building material.

Douglas Fir Association/Princeton Architectural Press

The A-frame—essentially an equilateral triangle in which the roof and walls form one surface descending to the floor—transcended geographical, social, economic, and stylistic bounds to become the iconic vacation home of the postwar era. It could be the embodiment of contemporary geometric invention, or a steadfast, timeless form suggesting nature and rustic survival. It was a place to hide out or a place to show off. From Nathaniel Owings’s grand design overlooking Big Sur to the small plywood shacks advertised in Field and Stream, there was an A-frame for almost every budget. It was strong, easy to build, and seemed appropriate in any setting. Perhaps most appealing, the A-frame was different with an individuality that suggested relaxation and escape from the workaday world.

The Inspiration for A-frames

Triangular buildings did not always hold such playful connotations. So-called “roof huts” turn up in ancient Japan, Polynesia, and throughout Europe where they functioned as cooking houses, farm storage sheds, animal shelters, and peasant cottages. Some survived into the 20th century, perhaps to influence several Swiss and German architects who rediscovered the form in the 1910s and ’20s. Imbuing it with a nostalgic nationalism, designers Albert Reider, Paul Artaria, and Ernst May proposed the A-frame as a response to the post-World War I housing shortage, as well as for early versions of the weekend mountain hut.

Architect Rudolph Schindler’s 1934 Bennati House in Lake Arrowhead, California, is one of the first known all-roof vacation homes in the United States.

R.M. Schindler Collection, Architecture and Art Collection, University of California-Santa Barbara/Princeton Architectural Press

In the United States, the A-frame had long been used for ice houses, pump houses, field shelters, and chicken coops, but no one thought to live in them by choice. This view changed in 1936, when Rudolph Schindler designed an A-frame home for Gisela Bennati on the hills above Lake Arrowhead, California. To meet building restrictions in the private resort community, the Austrian-born architect passed the house off as “Norman-style.” Though a departure from much of Schindler’s modern work, it did reflect his interest in geometric roof forms and the dynamic interior spaces that resulted from their use. With a glazed gable end oriented toward the view, an open plan, and extensive use of plywood, Schindler’s A-frame was a modest, postwar vacation home built 20 years ahead of its time.

It was not until the prosperous post-World War II era that conditions were right for the widespread adoption of triangular vacation homes. The first phase in the A-frame boom (between about 1950 and 1957) saw gradual exploration by a succession of aspiring young designers, many based in the creative architectural environment of northern California. Through their work, the A-frame vacation home in all its myriad variations took shape. They developed ways of enclosing or opening the gable ends, laying out the interior, orienting decks and entrances, inserting dormers and combining frames to make cross-gabled or T-shaped variants-common approaches that would appear again and again when the form began to take off near the end of the decade.

In 1950 Wally Reemelin, an industrial engineer interested in efficient architecture, built a pair of A-frames in the hills above Berkeley, California. Almost concurrently, Interiors magazine published an A-frame by San Franciscan John Carden Campbell in a collection of new architecture. Over the next few years George Rockrise developed a cross-gable design in Squaw Valley, California, Henrik Bull built one in Stowe, Vermont, and Andrew Geller built another in Amagansett, Long Island. (Both Eastern A-frames launched successful vacation-home design careers for their architects.) Yet it was John Campbell’s version, called the Leisure House, which first aroused popular interest and hastened the spread of the A-frame nationwide.

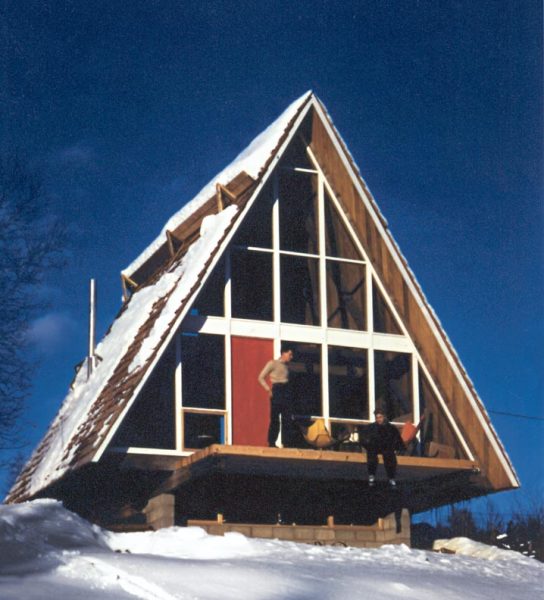

MIT student Henrik Bull brought the form East when he designed this two-story A-frame in Stowe, Vermont, in 1953—possibly the first in the area.

Henrik Bull/Princeton Architectural Press

With a smooth plywood exterior, stark white interior, tatami mats, and butterfly chairs, Campbell’s design reveled in its modernist purity. He was fond of saying that the house enclosed the most space in the most dramatic way for the least amount of money. By fixing its dimensions to a 4‚ module (the width of a sheet of plywood), he further reduced costs and simplified construction of a design that was already cheap and easy to build. From the beginning Campbell saw his A-frame as a potential do-it-yourself project open even to “novices who are all thumbs.”

After exhibiting a full-sized model at the 1951 San Francisco Arts Festival, Campbell received a stream of calls requesting more information about the Leisure House. He began selling plans out of his office and moved quickly to develop a precut kit that contained everything needed to assemble the house, from timber to nails and hammer. The kit appeared in innumerable articles (most notably in Look magazine) and at home shows, sporting good fairs, and department store promotions across the West. In 1952 Campbell built his own Leisure House across the Golden Gate Bridge in Mill Valley. In short order he established a small network of dealers offering precut packages in Los Angeles, Denver, and New York. Photographs of the A-frame hanging out over Mill Valley appeared in franchise brochures, magazine articles, and plan books for the next 20 years.

John Campbell’s Leisure House, featured at the 1951 San Francisco Arts Festival, was high-art modernist design, yet affordable to the masses.

Ernie Braun, courtesy of Eichler Network Archives/Princeton Architectural Press

Leisure Life for the Masses

The Leisure House marked a new phase in A-frame history. It was influential not so much for Campbell’s interpretation of the triangular structure, but for the way it was packaged and promoted. Campbell presented the Leisure House as a natural design for mountain or beach, for summer cottage or winter ski cabin, a fun vacation home form that was contemporary and different yet reassuringly traditional. It was inexpensive enough for young couples to afford, and simple enough for weekend carpenters to assemble. In these ways the Leisure House embodied a new leisure culture.

The spread of the postwar vacation home phenomenon and the excitement stirred by the first generation of custom-designed A-frames did not go unnoticed by the building industry. By the end of the decade, building product manufacturers and trade associations grown rich on the 1950s housing boom and looking for new markets beyond the suburbs, began offering vacation-home plan books that included material lists filled with their products. They teamed up with local builders, lumberyards, and hardware stores to offer precut vacation-home kits and construction services. Instantly recognized and appealing to a wide variety of customers, A-frames were often the centerpieces of these programs.

This stack-gabled A-frame at Aspen Highlands ski lodge in Colorado has overlapping gables that lend an air of sophistication to the slopes. (Photo: Pepi 2/Princeton Architectural Press)

The Douglas Fir Plywood Association (DFPA), based in Tacoma, Washington, was one of the first organizations to see the vacation-home boom coming. In 1957 DFPA marketers heard about an A-frame design drawn up by David Hellyer, a local pediatrician and amateur builder. They offered Hellyer free plywood in exchange for the use of his plans, photographed the house as it went up, and featured it prominently in their nascent promotional campaign. Within the first few months of publishing Hellyer’s A-frame, the plywood association had filled more than 12,000 orders for complete working drawings. Over the next decade, it appeared in publications as varied as the Journal of Medical Economics and the American Automobile Association’s American Tourist. The DFPA was onto something, and a host of other organizations and companies followed suit, all hoping to cash in on the A-frame’s increasing popularity.

During the 1960s, the A-frame zeitgeist became national. A-frames dotted ski slopes from Stowe, Vermont, to Squaw Valley, Idaho, and their variations were a common sight in the resort communities, lake shore areas, forests, and back roads between these meccas. In the process, the triangular building form became a cultural icon-architectural shorthand for leisure living and the good life. A-frame dollhouses and backyard playhouses let kids in on the fun. A-frames appeared in the background of ads for motorcycles, snowmobiles, and gas-powered toilets (the “Destroilet”). They were even given away as grand prizes at home shows and mail-in sweepstakes sponsored by frozen vegetable companies.

A Triangular Form in Eclipse

Fun has its fashions, however, and by the first years of the 1970s, the modest A-frame was an anachronism. Vacation homes had increased in size and retreated from the earlier whimsical tendencies until there was little to distinguish them from permanent houses. Real estate prices rose so high that it made little sense to build a $10,000 A-frame on an $80,000 lot. The energy crisis later in the decade further curtailed demand for remotely located, uninsulated, and notoriously difficult-to-heat vacation homes. Condos and time-shares became a preferred option for those who earlier may have selected an A-frame. Yet some elements of A-frame design lived on. Living rooms with vaulted ceilings, loft areas, and large, glazed gable ends—signal features of postwar triangular shelters—became common in permanent homes in the 1970s.

Twenty-five individual A-frame units at the Ranch Motel in Rice Hill, Oregon, are still in existence. (Photo: Chad Randl/Princeton Architectural Press)

Today, with recreation land in short supply and in great demand, A-frames built in the 1950s and 1960s have fared poorly. Those that aren’t promptly demolished to make way for 6,000-square-foot Mc (Vacation) Mansions are turned into the mudrooms or entryways for much larger homes. Just last year, George Rockrise’s 1954 cross-gable design, featured in countless magazine articles throughout the period, was torn down by a new owner more interested in the prime Squaw Valley property on which the house sat. Others have hung on, mostly forgotten and often remodeled beyond recognition. Wally Reemelin’s Berkeley A-frames survive, as does David Hellyer’s DFPA double-decker near Olympia, Washington. In contrast, two floor joists tucked beneath a much expanded structure are all that remain of John Campbell’s Mill Valley Leisure House.

Recently, a few aficionados of mid-century modern architecture have bought A-frames and brought them back to their 1960s appearances. While some are restoring old A-frames, others are building them anew. In 1998 architect Steven Izenour of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates built a distinctive A-frame library and sculpture studio for the Acadia Summer Arts Program in Maine. For folks interested in a typical triangular vacation home, plans are still floating around, most dating from the A-frame’s heyday. Recently, I met Larry Stover, an electrician and amateur builder, who used a set he bought on the Internet for his lot on the Green Briar River in West Virginia. It turned out to be a copy of Hellyer’s drawings from 1957.

During the early 1960s, 300,000 families a year bought or built a vacation home. Many chose a design that, though rooted in ancient building traditions, seemed an appropriate backdrop for the pastimes of postwar prosperity. A-frames were in harmony with nature, blurred the distinction between interior and exterior, could be built by those who wanted to do it themselves, and were easily packaged into affordable kits. They brought the dream of a second home within reach of an ever larger number of Americans.