Typical of a towerless middle-class house is this Red Hook, New York, example with a handsome veranda across the front and a projecting upper bay in lieu of a tower. It is a type that might be found anywhere from Maine to California in the 1870s and 1880s.

For a time in the middle of the 19th century, what set the pace of architectural taste for well-heeled Americans was not some ideal of the ancient past but all things in vogue during the regime of Louis Napoleon (1852-1870), or the era called the French Second Empire. Even after the Franco-Prussian War ended in 1871, Second Empire-style buildings continued to ride high on a tide of huge, newly minted, post-Civil War fortunes that were amply equipped to handle these extravagantly decorative houses. The Second Empire style, with its ubiquitous mansard roofs and heavy ornament, remained the first choice of wealthy homebuilders and their architects because it was, in their eyes, not only thoroughly “modern,” but also fashionably flashy in what was a very flashy era indeed.

A History of the Mansard Roof

Not all mansard houses were spread out; many were designed to fit narrow lots while keeping their hallmark rooflines and towers. This 1870s house in Rhinebeck, New York, has traditional Second Empire features, with distinctive window ornaments and lintels.

The emblem of the style is the distinctive mansard roof, a device attributed to the 17th-century French architect Francois Mansart (1598-1666). Mansart is remembered by architectural historians as the Father of French Classical Architecture, but he clearly had a practical nature as well. The point of Mansart’s dual-pitched roof was to squeeze a full floor of living space above the cornice line of a building without increasing the technical number of stories in the structure—an economically appealing bit of architectural legerdemain in a city like Paris where upward mobility, at least in buildings, was restricted or heavily taxed.

The top of a mansard roof is generally broad and flattish in order to maximize the volume of space beneath it—think of a hipped roof with its top surface spreading almost to the edges of the building. The lower pitch may be convex (outwardly curving, possibly in an S or bell shape), concave (inwardly curved or flaring), or steeply angled. Sometimes the mansard roof is two stories high.

Whatever the exact shape of the roof, there are always numerous dormer windows to light the living space within. Second Empire features and mansard roofs are so often found together that the style itself is frequently referred to as the Mansard Style. While it is true that every Second Empire house has at least one mansard roof (and some have many), does the presence of a mansard roof always signify a Second-Empire house? In a word, no. In Second Empire buildings, the mansard roof must be the dominant feature, not a subsidiary one. You might, for example, have a Queen Anne house with a gabled main roof and a mansard-roofed tower. Such a house is still a Queen Anne, not a Second Empire. In the same way, many Stick- Style houses have mansard roofs—but they are not Second Empire because it is the Stick Style features that dominate the design.

One-story mansard houses pop up periodically, but certainly not in large numbers. This Topsfield, Massachusetts, house with a concave curved roof retains the usual dormers, a fine left-side bay window, and a distinctive console hood over the double front door.

As it happened, the purely French influence waned fairly rapidly in the architecturally freewheeling days of latter-19thcentury America. When France’s fortunes declined after the Franco-Prussian War, which was a disaster for the French, the prestige of things French suffered as well. Moreover, the rapidly growing ranks of America’s professional architects (trained, it is true, in the Paris studios of Ecole des Beaux-Arts masters) were intent on finding their own architectural paths. Consequently, houses and other buildings veered toward other styles even while sometimes keeping the distinctive mansard roofline.

The other popular modes of the day—Italianate, Queen Anne, Romanesque, High-Victorian Gothic—all captured the attention of the house-building public, and all continued to use bits of Second Empire decoration as well as the popular mansard roof.

Second Empire Style

Though mansarded mansions are less common in the post-Civil War South, the 1870 Heck-Andrews House in Raleigh, North Carolina, is exemplary. The tower’s convex roof contrasts with the deeply concave roof of the house.

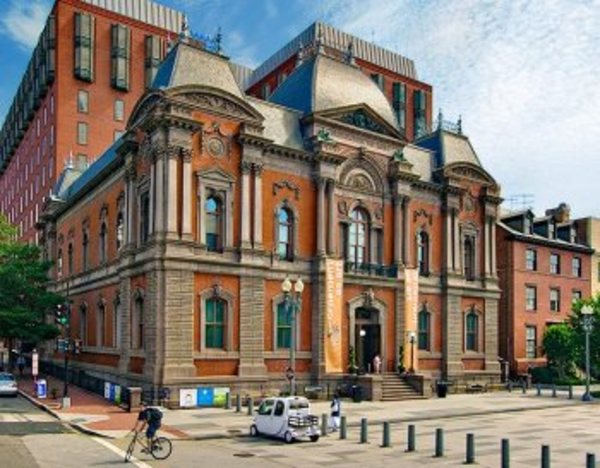

The Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC is considered the first true Second Empire building in the U.S.

The first true Second Empire building in the United States may have been the Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC, completed in 1859. Now part of the Smithsonian Institution Museum of American Art, it was built originally to house the extensive private art collections of millionaire William Wilson Corcoran. Co-opted during the Civil War as a government office building, it was returned for a time after the war to its owner before being put back into government service. The architect, James Renwick, also designed the Smithsonian’s celebrated Castle on the Washington Mall.

As a side note, Second Empire also is occasionally referred to as “General Grant Style” because it was most popular—in the U.S. at least—immediately after the Civil War and during Ulysses S. Grant’s presidency (1869-77). It was President Grant who called upon his Architect of the Treasury, the British emigre Alfred B. Mullett, to design the stunningly elaborate State, War and Navy Building (now the Old Executive Office Building) near the White House in 1871. (So why, you may ask, isn’t it called President Grant Style rather than General Grant Style? Who knows?) The State, War and Navy Building made Mullet famous and fueled a craze for French architecture among a postwar class of super-wealthy entrepreneurs (those famous and infamous “Robber Barons”) who made their fortunes in the likes of railroads, timber, land speculation, mining, and iron production.

This modest-frame Second Empire house in the Georgetown Historic District of Washington, D.C. carries the style in simplified form. The bay window, door, frontispiece, corner quoins, and modillion cornice provide a comfortable degree of ornament for a smaller residence.

The presence of great wealth and the new availability of a native corps of trained architects across the country—East, West, and Midwest— were among the forces that propelled the Second Empire to a truly nationwide American style. Advances in transportation (such as the Transcontinental Railroad, officially completed in 1869) and in printing (which promulgated architectural plan books and taste-making publications) were other reasons for the spread of the style.

Like Renwick’s and Mullett’s public buildings, high-style Second Empire houses featured a great deal of fancy ornament, especially around windows and doorways. While elaborate window and door surrounds of masonry were not uncommon, cast-iron decoration often replaced stone, to excellent effect. One-story columns, paired columns, and pilasters perched, layer upon layer, from the tops to the bottoms of these residential wonders. Classical ornament abounded.

The Second Empire style was, at its purest, definitely not a practical style for the man of small means. Nonetheless, the mansard roof was so useful—both as a means of securing additional living space at the top of the building and as a device for adding visual heft and distinction to a small and simple building—that its use by all classes of homeowners was widespread. Even one-story houses could be dignified by the adding a mansard roof.

A glance around today’s proliferating historic districts will show that Second Empire is far from the most frequently found historical house style. It wasn’t an easy kind of house to build or to maintain—probably one reason so many of these mansarded mansions have become museums or other types of public buildings—and the style didn’t last all that long. Still, it is among the two or three most striking American house styles, and its presence in urban areas and early suburbs, as well as on country estates, is an enduring gift from our French friends—almost as precious, in its way, as the Statue of Liberty.