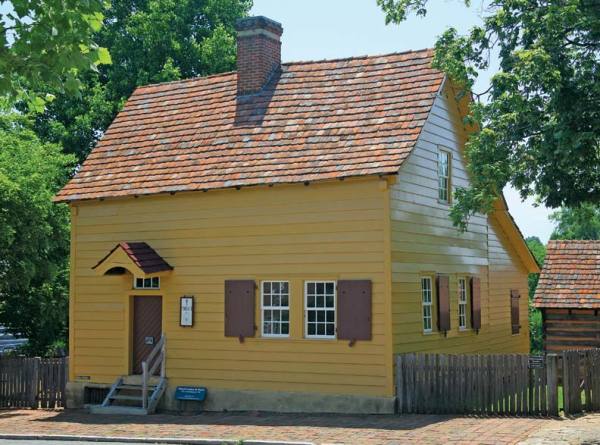

The log Miksch House was covered in clapboards and painted yellow soon after its construction in 1771; like all early Salem houses, it was roofed in tiles made in the village.

Hidden in plain sight on the streets of modern-day Winston-Salem, North Carolina, is an architectural time capsule. Originally the home of a peaceable religious community, this remarkable National Historic Landmark District holds a collection of authentic, in situ 18th- and 19th-century structures that reflect the Germanic traditions of Salem’s Moravian founders.

The buildings range from privately owned houses to churches, schools, shops, and other public buildings, including the museum village of Old Salem. With Bethabara and Bethania, two smaller Moravian sites nearby, they present an intriguing snapshot of an Old World culture caught in the act of adapting to New World conditions.

Building Traditions

The town’s plan, drawn up by Christian Reuter, featured a central square surrounded by community buildings. Except for the church, the Single Brothers House (1768-1769) was the largest and most important of these, since it would provide living and working space for the small band of skilled craftsmen sent from Bethlehem to build the village. After the village was established, the structure would house all of Salem’s bachelors—every unmarried man above the age of 14—hence the name “Single Brothers.” Quarters for unmarried women and adolescent girls (“Single Sisters”) would be built a bit later.

The showpiece of the Moravian settlement was the large Single Brothers House, built in 1769, with a brick addition in 1786. The unmarried men of the community had both their workshops and their living quarters here until 1823.

Married couples were allowed to erect their own homes, which, in light of the Moravians’ task-based belief system, usually included workshops with separate entrances for customers. The land supporting these home workshops was held in trust by the community, which also built separate boarding schools for boys and girls.

Salem’s Moravians used construction techniques they knew well from their previous life in Europe, but New World materials required some rethinking. They would have preferred, for instance, to build two-story houses of stone or brick, but stone found in their first years in North Carolina was no match for that of Germany, and the initial scarcity of high-quality lime for mortar limited all-brick construction.

Many houses have small and practical entrance porches.

Thus, builders were forced to revert to the use of traditional Germanic fachwerk, or half-timbering. Fachwerk required a massive wooden framework interspersed with handmade brick. The Single Brothers House is an imposing two-story building topped by a two-story attic in the German style. A superb example of fachwerk construction, it is also a traditional Germanic “bank house”—i.e., one built into a hillside in order to accommodate a full-story basement on the back of the building. A pent eave, also a typically Germanic feature but one not often found in Salem, extends across the walls between floors to shelter the lower surfaces from the weather.

The two-story Single Sisters House (1785-1786), or women’s dormitory, was a masterwork of Salem’s exceptional brickmason, Gottlob Krause, with oversized bricks laid in Flemish bond. The house has fine arched window openings, a double attic, and its original tiled roof.

Early houses for married couples were small and simple, usually of brick or frame construction with stone foundations, but occasionally of logs. Along the edge of Old Salem, a group of small, privately owned, one-story homes charmingly displays carefully restored fachwerk and intact two-story attics.

Third House is part of an early group of houses, originally built in 1767 in the Germanic tradition with half-timbered walls and a steep tile roof.

Steeply pitched roofs, with a barely noticeable “kick”—a slight upward curve at the corners, created by inserting a wedge under the tiles at the roof’s edge—are a universal trait of Salem houses. Center chimneys were an ingenious and economical means of heating two rooms with a single fire, with an open fireplace in one room backed by a tiled stove (made in Salem’s busy workshops) in the second room. As the years passed, the steep roofs remained, but Salem assimilated many features of its non-Germanic neighbors’ house styles. Chimneys migrated to the gable ends of the house, and center halls produced symmetrical façades.

Double-hung sash windows were topped by segmental masonry arches, a distinctive feature of Germanic design. Double wooden Dutch doors, sometimes with boards arranged in a herringbone pattern, or with one wide and one narrower panel, opening separately, were hung on prominent iron strap hinges.

Evolving Mix

The 1825 Butner House illustrates the gradual Anglicization of Moravian Old Salem.

In the beginning, only Moravians were allowed to live in Bethabara and Salem, but some non-Moravian residents were permitted in Bethania, so not all the early buildings there derive from Germanic traditions. Adding to the cultural mix, the adjacent village of Winston, which had English antecedents, overtook Salem in size and wealth during the rapidly industrializing 19th century. As the influence of the Moravians’ theocratic government waned, the two towns became interwoven. They officially merged in 1913 to form Winston-Salem, a manufacturing hub that was—for a time, at least—North Carolina’s largest and richest city.

Today, Salem’s landmark district shifts subtly from private homes to church-owned buildings (like churches and the Moravian Archives) to public institutions, such as schools and colleges, to museum properties and re-created vegetable and medicinal-herb gardens. Modern streets lined with brick and stone sidewalks run through the old town, now a small corner of the metropolis of Winston-Salem. Sorting out the centuries can take some thought, but it’s worth the effort. And if, on the way to the Moravian burial ground, God’s Acre, you suddenly find yourself standing before a 7′-tall tin coffee pot, rest assured you haven’t lost your way (or your mind); it’s an 1858 advertising symbol fashioned by Salem’s Mickey brothers for their tinsmithy. Both the pot and the cemetery are sturdy monuments to faith and industry: fitting symbols of Old Salem.

Online Exclusive:See our picks for other historic religious settlements to visit.