The Byrne-Reed House in Austin, Texas, recently underwent a dramatic restoration that removed its 1970-era shell and returned its original appearance and finely crafted details.

Once upon a time, an unremarkable, 1970s mausoleum-style building sat at the corner of 15th and Rio Grande streets in downtown Austin, Texas, its white stucco façade and unadorned columns casting sharp rectangular shadows in the Texas sun. Today, cars slow at the intersection to soak in the beauty of that same building, now restored to its original early 20th-century appearance.

Distinctive Beginnings

Long ago, the house was a turn-of-the-century beauty, designed by C.H. Page, Jr., a local “it” architect of his time, and built in 1906 for a prominent local family, the Byrnes. Its style might best be described as “Texas eclectic”—with Spanish-style terracotta roof tiles, Richardsonian Romanesque arches, Prairie-style porches, and Art Nouveau friezes tucked under the eaves, it melded many architectural styles, defying true categorization. Yet its architect’s attention to detail on many levels, as well as his undeniable desire for beauty, was truly remarkable. In 1915, Mrs. Byrne died disappointingly young, and Mr. Byrne moved closer to their daughter and sold the house to the Reed family.

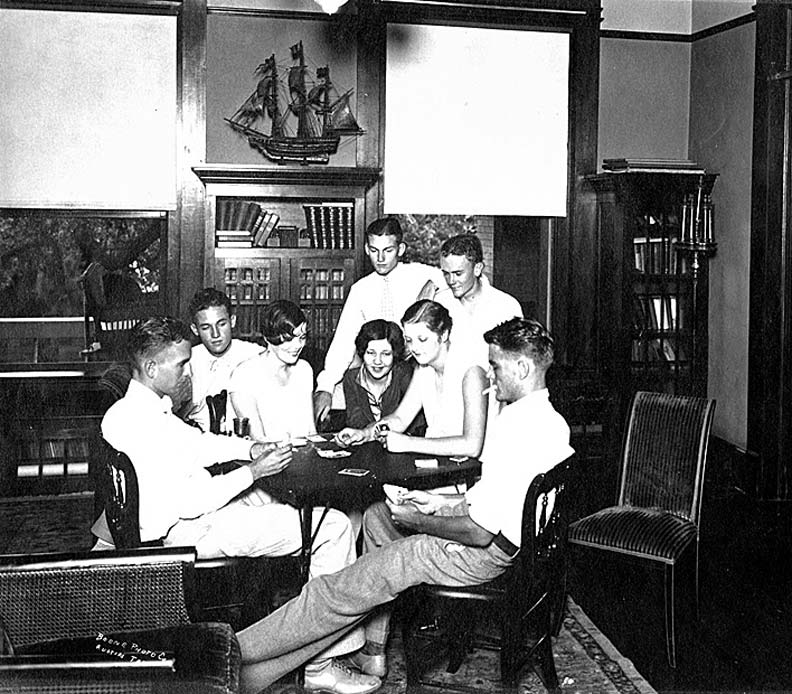

David Reed wore many hats in central Texas, buying and exporting cotton, serving on the local school board and city council, investing in oil development and the iconic Driskill Hotel, even maintaining a close friendship with then-Congressman Lyndon B. Johnson. The Reeds would make this their home for three and a half decades, raising a family and even marrying a daughter here. They remodeled the house twice, moving a couple of interior walls to create a larger living room. Upon David Reed’s death in a plane crash in 1948, the building’s fortunes changed dramatically.

In 1952, an insurance company purchased the home and modified it for use as an office building. In 1969, stucco was wrapped on a steel frame around the entire building—“a 1970s stucco slipcover,” says architect Ken Johnson, one of a phalanx of knights in shining armor who would ultimately rescue the home from this shroud. At the same time, a line of soldier-straight, two-story columns was added along the north façade. By 2000, the once-lovely home was unrecognizable—a behemoth, stuccoed office building. With its square shape, tall rectangular windows, and overall lack of curves, it looked like something that could have been designed with Legos.

Intricate plaster moldings and appliqués were returned to the dining room.

Inside, the changes were a history buff’s horror story. The sprawling porch had been enclosed and divided into offices, its tile floor drowned in concrete. Interior doors and windows had been masked with drywall and stucco, and ceilings had been dropped with acoustic tile and florescent lighting panels. Architect Emily Little describes its pre-restoration condition succinctly: “It was a mess.”

Turning Tides

The hero of our story is Humanities Texas, a nonprofit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The organization had been looking for a new home for some time, says Michael L. Gillette, its executive director. “We wanted a building that evoked heritage,” he remembers. “We didn’t want a glass box.” They wanted to be downtown, too. So although the stucco-ensconced building didn’t exactly scream “heritage”—at least not the kind they had in mind—in 2006, Gillette and the Humanities Texas board took a leap. Like the princess who kissed a frog without knowing just what would happen, they bought the building, intending to restore it. They would spend the next three and a half years raising funds from a variety of sources for what would ultimately be a nearly $5 million project. Austin architectural firm Clayton & Little mapped out the restoration.

Victorian geometric tiles on the front porch were unearthed beneath 4″ of concrete—they remained virtually unscathed.

The Humanities Texas staff and a collection of traveling exhibits already occupied the building when construction began, so the architects and contractors started demolition on a micro scale to avoid disturbing the workspace. They cut more than a dozen holes, each 2′ square, into the drywall and stucco at strategic locations on the building’s interior and exterior. Each hole was big enough to peer into, an attempt to get a peek at what lay beneath. But the holes didn’t prepare the team for a series of stunning surprises unearthed as demolition got underway in earnest.

Tile fragments excavated in the garden confirmed the original roof’s manufacturer—Ludowici—who was able to provide a perfect match.

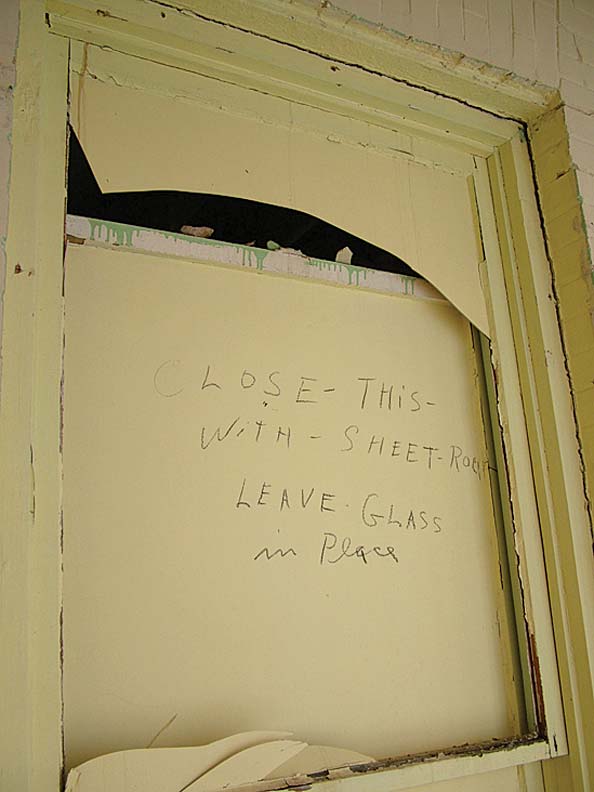

The surprise that Gillette remembers as “probably the most exciting discovery” came on the porch. Contractors pummeling through the 4″-thick concrete floor were amazed to find original geometric tile beneath it. The concrete hadn’t adhered to the tile, so it released easily. Consequently, the majority of the tile was left essentially unblemished; most tiles needed only a rudimentary cleaning. Other surprises ranged from the mundane to the fortuitous. A toilet paper roll sitting on its holder inside a wall was simply a colorful anecdote. But the crew also found two historic windows in their entirety—original sash, intact glass, functioning hardware, and even screens in place—completely encased in stucco and wood paneling. One window was left open in what seems to have been a harried remodel.

Then there were the surprises most home restorers can only dream of uncovering. A segment of wrought-iron railing from a second-story porch was found embedded in a plaster wall, and used as a guide to replicate its missing kin. A couple of sections of the concrete railing that had surrounded the first-floor porch remained intact, entombed inside an exterior wall, and also were used to guide replacements. Many sections of the original plaster frieze that had crowned the building, as well as parts of the concrete capitals that topped the porch columns, were likewise uncovered intact.

Perhaps most helpfully, pieces of the home’s original clay roof tiles were unearthed during excavation for utilities—they had apparently been thrown into the yard when they were replaced with standard-order composite tiles some half a century ago. One tile still bore its manufacturer’s name: Ludowici-Celadon Co. That same company, now known simply as Ludowici, was contracted to match the original tile to restore the entire 5,100-square-foot roof.

It took Martin Diaz, Sr., a plaster craftsman with three decades of experience, six weeks to develop a technique for re-creating the unusual scalloped texture of the original exterior walls on the house’s first-floor porch.

As the demolition continued, the villains of our fairy tale—the remodelers who had betrayed the home’s history with their heavy-handed changes—started emerging as unlikely saviors. Wittingly or not, they had preserved much of the home’s story even as they obliterated other parts. The words “leave glass in place” were discovered in pencil on one sheetrock-enclosed window. Could that have been a worker’s attempt to leave a clue for future restorers?

Photo Finish

Not all of the team’s guidance came from the demolition process. They also were armed with historic photographs contributed by descendants of both the Byrne and Reed families. The team used the photos at the beginning of the project to identify targets for the exploratory holes, then later as guides for restoring details, from exterior plasterwork to the staircase inside. “We couldn’t have done it without them,” says Little.

Some details stared out plainly from the photos—the plaster trim around the porch arches, for instance. Others emerged more subtly. When restoring the partial wall at the base of the house’s grand central staircase, for instance, the architects had little to go on. Then Johnson noticed a shadow on the wall in a bridal portrait from Ruth Reed’s 1934 wedding. The shadow clued him into how, at the time, a piece of carved wood decorating the landing had curved back on itself before abutting the adjacent wall. The architects built a cardboard mockup of the shape they thought would create that shadow and set it in place to make sure they had it right before having a local woodworker Joe Zambrano carve the final piece.

The railing’s scrolls were re-created with the help of intricate tracings.

The photos also helped supplement information the architects dug up from the city’s records. A broad understanding of the house’s history guided their decision to restore the exterior to 1907, the year the home was completed. Inside, though, they opted to take it back to 1948. The slightly altered Reed floor plan from that year better suited the functionality Humanities Texas needed from the building. The team also thought it made sense to reflect the imprint both families had left on the house.

The staff of Humanities Texas and the architects who planned this restoration hope to do more over time. Toward the project’s end, a visiting antiques dealer recognized carvings in the house as the work of Peter Mansbendel, a local wood and plaster carver who was prolific throughout Texas during the early 20th century. That led architect Little to explore an archive of Mansbendel’s work, eventually coming across a photograph of the original fireplace in the Byrne-Reed House’s main hall. Before they stumbled upon this information, the team had opted to keep the fireplace as simple as possible in the absence of data about its original appearance. Now they hope to restore it one day. But even without the reproduced mantel, the house is already living its happily ever after.

Online Bonus

Watch a time-lapse video of the Byrne-Reed House’s incredible transformation!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubbZdZE1pt4" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen=""><