The open floor plan feels spacious even within the 18′ x 28′ dimensions of the cottage. Celtic-design pillows by Archive Edition Textiles sit on a reproduction settle. A vintage braided-handle jardinière from North Carolina sits near the hearth. A locally made rhododendron-twig side table holds a Clark House pot.

William Wright

Half-hidden in the trees, the mountain cabin is called Ravenscroft. Owners Chas Fitzgerald and Jackson Hammack chose the name in homage to the raven—the secret keeper of wisdom in Cherokee lore—and for the Scottish “croft,” a small parcel of land.

Chas has been infatuated with the Arts & Crafts movement since his childhood, when he spent summers sleeping in the eaves of his grandparents’ bungalow. Even then, he kept notebooks filled with his designs for houses, and he made miniature towns out of scrap wood (and sold them to friends). It’s no surprise that he finished architecture school and became a historic-restoration specialist, establishing a thriving renovation business in Dallas with his partner, Jack Hammack.

When the two discovered Asheville and the historic Grove Park Inn’s annual Arts & Crafts Conference, they became devotees of the annual event. One afternoon, on their way to a rock-climbing expedition on Black Mountain nearby, they were sidetracked when they stumbled on a neighborhood of handsome—and apparently new—Arts & Crafts houses nestled in the with houses built in a vernacular that suits the forested site. Arriving home in Dallas, they came to terms with what they’d done: agreed to buy a lot and build a house within two years.

A “tree house” in Cheshire parlance, the three-storey cabin extends living space into the woodland canopy.

William Wright

Chas purchased stock plans from Southern Living and adapted them, keeping costs manageable. The plans were for a 1400-square-foot, two-storey “bungalow.” Because the lot is long and narrow, and set on a steep slope, Chas added underneath a daylight basement, affording a third level of living space without altering the modest footprint. (Access to the lower level is through a door hidden in the paneling beyond the main-floor fireplace.) Porches were then stacked over the basement-level patio to invite mountain views.

The goal was to make the home seem as if it had been built in 1914, inspired perhaps by early 20th-century Asheville architect Richard Sharp Smith. His Arts & Crafts detailing was used here: pebbledash stucco on the upper level, a heavily bracketed entry porch, woodsy exterior paint colors. Local Doggett Mountain rock was used for rustic stone piers that support the porches.

Reliance on local materials and tradespeople continues inside. Rough-sawn poplar woodwork is finished with linseed oil; metal handrails are by a local blacksmith. The ceiling is covered with tongue-and-groove pine paneling, painted coffee brown and then hand rubbed with blue paint for a pickled finish. The main floor is open for a spacious feel and easy entertaining. Broad, three-over-one double-hung windows enhance the sense that this is a tree house. The dining area is centered on a handsome mantelshelf made from a single piece of 100-year-old hickory, with a fireplace surround of forest-green tiles found at a salvage yard.

The Amish-made table and chairs are hickory; lantern and sconces are ca. 1920; the North Carolina double-handled pot is vintage.

William Wright

In the adjacent kitchen, custom cabinets at varying heights are interspersed with open shelves filled with locally made plates and mugs. Cabinets are painted in soft colors—nature-inspired greys, blues, greens, and browns—to lessen the visual impact of the kitchen from the living area.

The seating area on the opposite side of the dining room is furnished with comfortable Old Hickory chairs and a sturdy oak settle facing the porch and the vista. Local interest and color are provided by North Carolina pottery, folk art, paintings, and camp blankets.

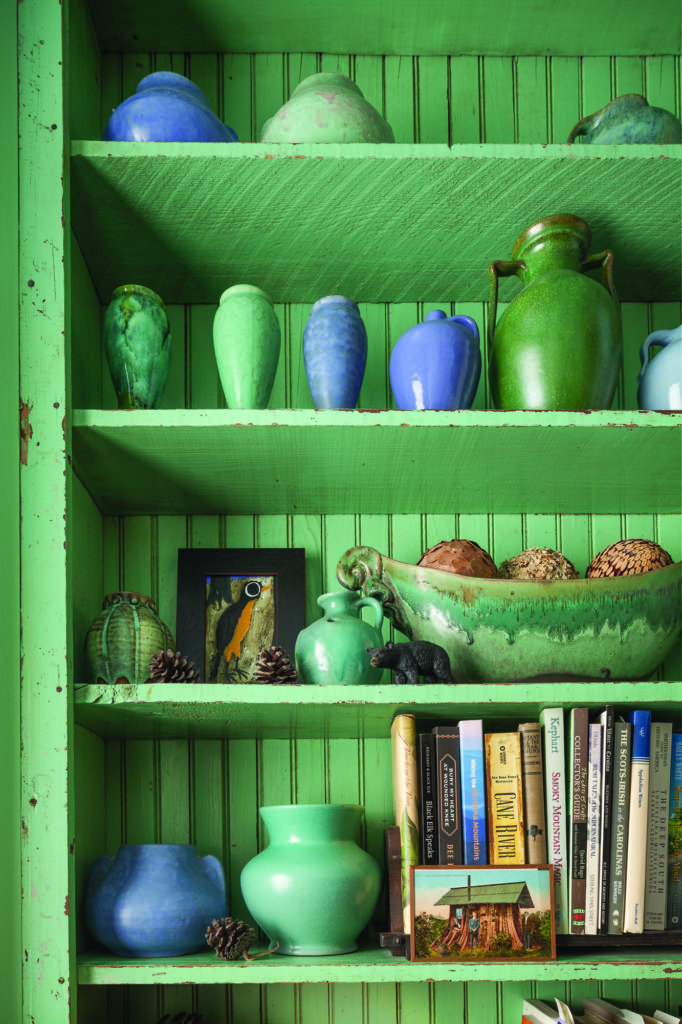

Upstairs, the master bedroom and bath are accompanied by a small study. The bedroom was designed like a bungalow-era sleeping porch, with pale blue walls and a deeper blue tongue-and-groove ceiling. The bedroom opens to the upper porch, an aerie for reading and catching a breeze. Local salvage finds include a wonderful, crusty green, open-shelf bookcase and old wooden spools repurposed as closet door knobs, a reference to North Carolina’s textile mills. (The Beacon Blanket mill was just a few miles away; now the mills have all closed.)

Mixing what’s local with the exotic, the lowest-level guest bedroom is a departure that still features handcraft. The hand-embroidered hanging from India is vintage. Salvaged windows above the bed let light into the Moorish bathroom beyond.

William Wright

A second bedroom and Moorish-style bath occupy the daylight-basement “addition,” which opens to a private patio. Salvaged windows that allow light into the bath make the room feel like a cabin. The hickory-log bed was made locally, and the raven pillows were made like the latch hook rugs once created by mountain women to sell to tourists.

Outdoors, the small yard has been planted with native favorites: Carolina hemlock, red maple with its brilliant display of fall color, and the graceful, drooping river birch. Mountain laurel is covered in pale-pink blooms in May, and drought-tolerant catawba serviceberry fills in the understory. Virginia bluebells, wild ginger, trilliums, and bloodroots provide ground cover.

A bookcase in the study displays more of the owners’ extensive collection of North Carolina ceramics, along with colorful camp blankets made by local textile mills.

William Wright

The Village of Cheshire is a Traditional Neighborhood Development: a compact, mixed-use neighborhood where homes are within walking distance of a town center. Cheshire was designed by Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater–Zyberk (DPZ), noted for downtown revitalization and earlier traditional developments including Seaside in Florida.

Residences in Cheshire fall into three categories: single-family, town homes, and tower or “tree” houses. The latter are smaller-footprint homes that occupy the steeper terrain on the hillside but do not require significant cut and fill during construction. Buildings are individually designed for a pleasing nonconformity, while guidelines ensure architectural integrity. Learn more at villageofcheshire.com and dpz.com.

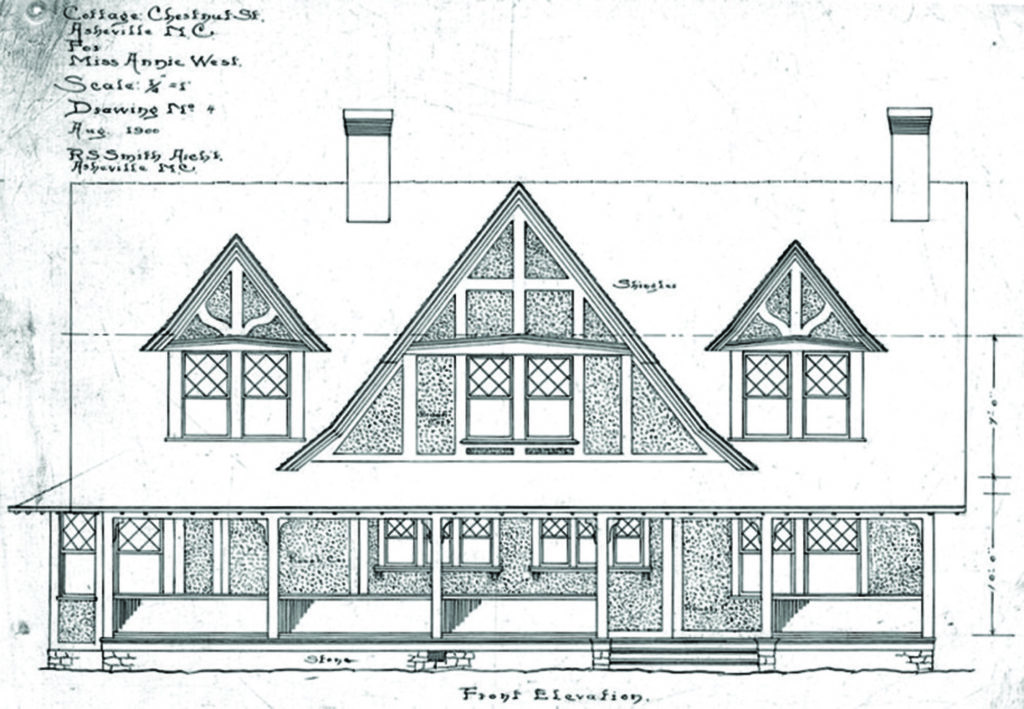

Richard Sharp Smith

Courtesy N.C. Division of Archives and History

Architect of the Vernacular: Richard Sharp Smith

The British-born architect Richard Sharp Smith (1852–1924) came to Asheville in 1889 to be the supervising architect for George Vanderbilt’s Biltmore House, in the employ of Richard Morris Hunt. Smith remained in Asheville and eventually became one of the area’s most influential architects, contributing to the city’s unique and historical character. He designed a wide range of buildings—residential, ecclesiastical, and civic—in styles from Arts & Crafts and Tudor Revival to Colonial Revival and Neoclassical. He was responsible for nearly every major building in downtown Asheville in the period 1900 to 1920 (after 1906, as half of the partnership of Smith and Carrier). Smith also designed many fine houses in the surrounding neighborhoods, including Grove Park.