Most of the tourists who visit the Winchester Mystery House in San Jose, California, come for its spooky associations. Architecture buffs, on the other hand, are in for a jaw-dropping tour of Aesthetic Movement architecture and decoration. Built over and around a modest Victorian farmhouse, the mansion took 38 years to create (1884–1922) and was never really finished. The cost was $5 million, or $71 million in today’s currency. It is spectacular.

Turrets and bays, balconies with fancy railings, irregularly shaped windows, and a “door to nowhere” together create a rich Queen Anne fantasy. From the roof on down, every surface is exuberantly ornamented with fish-scale shingles, ball-and-spindle decorations, turnings, carvings, and board siding at the base.

William Wright

The museum house is privately owned and heavily visited. The story told is that Sarah Winchester, widow of rifle heir William Wirt Winchester, was encouraged, during a séance, to leave Connecticut and head to California, to build an eccentric home for the spirits of all those killed by Winchester firearms. Money was no object: Sarah had inherited $20 million ($520 million today) and also had an income from her shares in the company—the equivalent of $26,000 a day in today’s currency.

Whether Sarah believed in ghosts, or was a mathematics prodigy dabbling in labyrinths and encryption, the house she built is a puzzle. It’s true that staircases spiral—or dead end; that doors open to nowhere; that the prime number 13 and spider webs are favorite motifs.

Beginning her project in 1884, Sarah Winchester (working without an architect or any blueprints) embraced the era’s popular Aesthetic Movement design. A challenge to the rigidity of classical art, the movement that started in England a decade earlier stood for “art for art’s sake,” welcoming beauty and the contemplation of beauty. It is the opposite of utilitarian design. Its architectural equivalent became known as the Queen Anne Revival, which morphed into the even more ornamental American Queen Anne style. Houses are picturesque, asymmetrical, heavily textural, and embellished.

Inside the house, gold and silver chandeliers hang from coffered and decorated ceilings over parquet flooring. Artful windows by Tiffany & Co. illuminate rooms filled with Anglo–Japanese pattern, lustrous Victorian tile, embossed Lincrusta wallcoverings, and carved wood.

Now four storeys, the house had a seven-storey tower before the 1906 earthquake, evident in this archival photo. Today Winchester Mystery House comprises 24,000 square feet in 160 rooms.

Courtesy Winchester Mystery House

The Aesthetic Movement & Queen Anne Style

Inside and out, every surface was ornamented. Color, texture, panelizing, and carving or embossing come together in a beautiful tapestry. Both Stick or Eastlake-style houses and American Queen Anne houses feature a multitude of architectural elements:

Terrell Lozada

• Steep, irregular rooflines may have cross gables, hips, and dormers. Roofs are further embellished with spires and pendants, iron cresting, and perhaps a griffin or dragon perched at the ridge end.

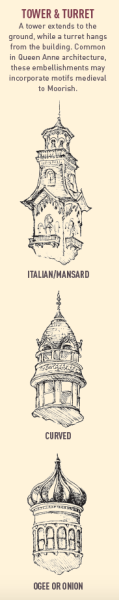

• Towers and turrets, with fancy-shaped roofs, are relatively common.

• Windows are generous in size and variety: find irregular shapes, muntin patterns, bows and bays, oriels, horseshoe windows, and Queen Anne sash with multiple square panes, often with colored glass.

• Surfaces burst with texture and embellishment: fancy-butt shingles, pebble-dash stucco, half-timbering. Shingles on roof and walls may create patterns or be polychromatic.

• Ornamental carving includes motifs from starbursts and sunflowers to more geometric Eastlake designs.

• Besides all the trim, woodwork extends to ball-and spindle spandrels and decorated balustrades on verandahs and balconies.

Embossed Wallcoverings

Metallic paper, wood trim, a Lincrusta dado, and hand-worked lace come together in the dining room.

William Wright

A sturdy wallcovering made from linseed oil and wood flour, Lincrusta–Walton was invented by the Englishman Frederick Walton in 1877. Similar to linoleum—patented by Walton in 1860—Lincrusta is embossed with steel rollers to create a decorative, three-dimensional surface. (A similar wallcovering made of embossed paper is called Anaglypta.)

Complex patterns are a hallmark of Aesthetic interiors; here, the wood cove has gilded beading and carved sunflowers.

William Wright

Sarah Winchester fell in love with Lincrusta, and bought dozens of rolls in myriad patterns, more than she could ever use. Around 70 rolls, many still in their original wrapping, are displayed in her storage room. Patterns range from Celtic knots to Anglo–Japanese waves and moons. Following the Aesthetic mantra of More Is More, Winchester covered ceilings, dadoes, and entire walls in a riot of patterns to create rooms rich in texture and stylized ornament. Lincrusta is sold unfinished and meant to be paint-decorated: to resemble tooled leather or carved wood, or to be polychromed, glazed, or gilded.

The Cult of Japan

Following the opening of Japan by Commodore Perry in 1853, Japanese art and objects were displayed and admired in England and America. Concurrent with the Aesthetic Movement, a derivative style called Anglo–Japanese soon emerged, blending asymmetrical geometry with such oriental motifs as bulrushes, waves, crescent moons, stylized “cracked ice,” owls, dragons and sea serpents, frogs, and spider webs. Flowers are common, too, and carry meaning: chrysanthemums stood for truth and grief, lilies for devotion, and sunflowers for good luck.

Many stained-glass windows were never installed, and today are displayed in Sarah’s storage room.

William Wright

Stained & Leaded Glass

A set of three beveled-crystal windows was commissioned in 1890.

William Wright

Stained and leaded art glass is an important component of Aesthetic Movement

design; colors are rich and motifs opulent. Scenes were often painted on the glass: bats in a night sky, owls perched on the crescent moon, swallows diving, along with sunflowers, chrysanthemums, and lilies. Sarah Winchester herself designed a spider-web window. A window by Tiffany has richly beveled and leaded-glass panes, meant to allow sunlight to cast a rainbow across the room; it was, however, installed on an interior wall, negating the effect. Much of the Winchester glass is stockpiled in a storage room. In the past four decades, glass has been expertly repaired, flattened, and reinforced by Mark Walton of Walton Art Glass (waltonartglass.com).

A carved, openwork screen creates a secret porch in the South Turret. Ball-and-spindle fretwork is found in spandrels above the screen and in brackets. Dubbed Winchester Gold, the ocher resembles the original body color.

William Wright

With ornate beveled glass, the front door is a tour de force set within a carved redwood archway.

William Wright

Woodwork

Woodwork—in the form of mouldings and trim, mantels, staircases, and carvings—was a critical component of rooms in the Aesthetic taste. Bold and dark, it girds the decorative embellishments on walls, ceilings, and furnishings. While the exterior of Winchester House is largely built of redwood, painted over, interior elements and trim also introduce a mix of hardwoods.

Bradbury’s ‘Herter Ceiling’ is used on the wall fill above the Lincrusta dado.

William Wright

In the lavish Grand Ballroom, the wood species used for the dominant Eastlake-style wall cladding are probably white ash and chestnut. Mantels in the Front Parlor and Dining Room are most likely cherry with a once-glossy varnish finish.