The gas flame on Valor’s Windsor Arch adjusts from 6,500 to 20,500 BTUs per hour.

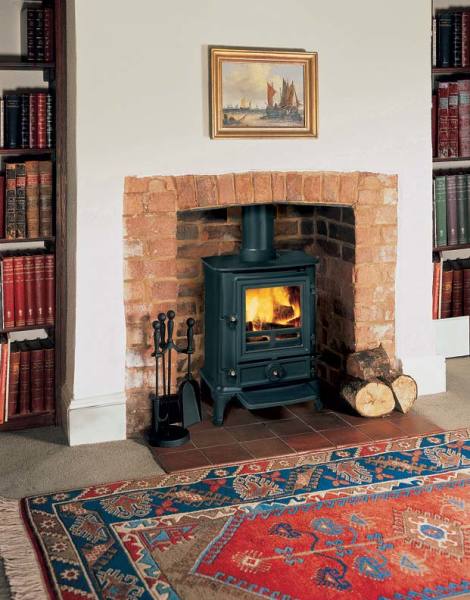

A crackling fire is one old-house accessory that’s always in demand on cold winter nights, adding warmth and ambience to a room. While wood- or coal-burning fireplaces traditionally kept folks warm in the depths of winter, modern inserts can do the same with aplomb. New units are more efficient, less polluting, present fewer safety hazards, and come in a variety of styles and sizes. Inserts and stand-alone coal baskets or woodstoves can be a good choice for retrofitting a traditional fireplace for better energy efficiency and safety, or for getting flames into a non-functioning original fireplace. They have historical precedent, too: Victorian gas fire-log inserts were a fashion statement beginning around 1890.

Today you can find an array of historic-minded inserts in a range of sizes that burn a variety of materials—from wood and gas to pellets and cherry pits. When making selections, size is one of the most important factors—both the size of your original fireplace opening and the size of your room. Small, old fireplaces can be hard to fit, while smaller rooms can overheat under today’s hyper-efficient, high-BTU inserts. Read on for more essential things to consider before buying a fireplace insert.

Concerns & Solutions

Warmth. Both wood and gas units can burn hot—up to 75,000 BTUs per hour, depending on their fuel and venting system (see “Crib Note Comparisons,” above). However, such revved-up output can overwhelm some old-house rooms—especially smaller ones measuring 15′ x 15′ or less with only one doorway. Pay attention to BTUs; when dealing with smaller room sizes, find either a lower BTU output (up to 30,000), or a unit that is easily adjustable (like a gas insert that readily turns down to a gentle 10,000 BTUs).

A plug-in coal basket from Burley throws 5,000 BTUs of heat.

Ease of use.If convenience is your most desired feature, consider a gas unit. Gas fires can provide heat at the touch of a button, can be as efficient as a gas furnace, and don’t require combustion products to be carried in or away.

Firebox size. Many old-house fireplaces have small or shallow dimensions that can be difficult to fit. One solution is a Franklin stove. These stoves, = designed in 1742 by Benjamin Franklin, have a hooded enclosure in the front and firebox in the rear—cutting-edge technology for the time that produced more heat and burned less wood in a safer fireplace. Because they are meant to sit in front of the fireplace opening on short legs, they work more readily with small openings, and their style is well-suited to the architecture of early houses.

Reversibility. If you want to be able to change your mind easily and remove the insert, or you’re more interested in ambience than warmth, an electric fireplace unit might be the choice for you. They can add the look of real flames, don’t need to be vented (so they can be inserted into a fireplace with a non-functional chimney), and can generate up to 5,000 BTUs of heat after a simple install—just plug it in.

Open flames. If you don’t want a glass-fronted unit, but want to increase the efficiency of your masonry fireplace, consider a gas log or coal set. (These work well in small fireplaces, too.) They burn cleanly and can throw a decent amount of warmth into a room. Caveat: These sets must be vented through terracotta or steel liners. If your house has neither, the price to add a steel liner will approach the cost of a full insert.

Word of Warning

Early inserts of the modern age (from the 1970s and ‘80s) often were installed improperly into chimneys too large to vent the flue gases quickly. When gases slow down, they can cool enough to allow extra creosote to condense on the walls—which can cause structural damage or even a chimney fire. Make sure chimney liners are correctly sized. The Chimney Safety Institute of America recommends that liners extend to the top of the chimney for safest operation, and be inspected annually on all chimneys in use. (For more information on chimney liners, click here.)

The Brunel 1A wood stove from Stovax is a Franklin stove lookalike.

Venting Systems Explained

Old-house wood- and coal-burning fireplaces have chimneys that vent smoke and draw air through their flues—which were lined with clay tiles beginning around 1905. Today’s modern inserts use a variety of sophisticated venting systems that are retrofitted into existing chimneys.

B-vent: Draws air necessary for combustion from within the home and vents the products of combustion outside the building.

Direct-vent: A closed-combustion system that takes no air from inside the home—it draws air in from outside and vents to the outside, through a single vent. Most direct-vent systems use a coaxial vent—two pipes in one that brings air in through the outer chamber, and vents air out through the inner chamber.

Vent-free: No chimneys required—these inserts use room air for combustion, and also vent into the room. They come with a standard Oxygen Depletion Sensor pilot (ODS), which shuts the burner down if oxygen levels in the room fall below a certain limit. While vent-free units quickly gained popularity after their introduction, they are controversial among many safety experts, who recommend installing multiple carbon monoxide detectors in homes where they’re used to guard against carbon monoxide buildup and poisoning. Additionally, they’re not approved for use in all areas, and can add significant amounts of water vapor to your living spaces, which can damage old plaster and wallpaper.

Want more tips on fireplace trends? Learn how to make the most of a freestanding fireplace.