This common, early 18th-century-type fireplace from Harriton in the “Welsh Tract” in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, has a simple surround, simple mantelshelf, and an overmantel panel. James C. Massey photo

Throughout our history, we have had a love-hate relationship with our fireplaces. Love that cozy look and feel; hate the mess and work. Mantelpieces, on the other hand, are more likely to fall into the pure-love department.

Mantelpieces—the various assembled components that make up the ornamental front of a fireplace—could be seen as the fancy outer dress of the home heating apparatus—the wood, stone, or iron equivalents of mink coats and designer gowns. The mantelpiece (also called chimney piece) is often the single interior element that sets the tone of the house and announces its architectural provenance, its age, and the prosperity, tastes, or aspirations of its builders and owners. Mantelpieces command attention, and as any interior designer worth the price of ASID membership will tell you, a room with a mantelpiece is a room with a Focal Point.

In the American colonies, mantelpieces were at first simple and utilitarian elements that befitted the hardscrabble life of the earliest settlers. Mantelshelves—handy spots to place useful or decorative objects—generally came later. In the 17th and early 18th centuries, heavy, rounded bolection moldings often surrounded the firebox opening in the brick or stone chimney, which was typically set into wood-paneled walls. The chimney breast was hidden by flanking cabinets and enclosed staircases that formed a continuous wall surface. Fireplace surrounds were of brick, and hearths were of brick or stone, but there was often a fancy cast-iron fireback (now an expensive piece of folk art) that protected the bricks at the back of the fireplace opening from the fire’s heat.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s masterly hand shines in his 1902 Heurtley House in Oak Park, Illinois. In the living room, a dramatic stained-glass skylight complements a brick fireplace that is unadorned except for its massive, Sullivanesque arched opening. Paul Rocheleau photo

Later, as the Georgian style drifted across the Atlantic from England in the 1750s and 1760s, more elaborate, formal treatments for walls, windows, doors, and mantelpieces appeared. Paneled walls and mantelpieces were now often painted. Large, pedimented overmantels of wood filled the space above the fireplace opening all the way to the crown molding below the ceiling. Crossetted, or “eared,” insets over the fireplace provided a perfect spot to display paintings. In the better houses, mantelpiece pediments often were as imposing as those on the doorways. In fact, it is surely no accident that mantelpieces so often resemble doorways, for they are indeed portals of a special kind.

Faux painting became common in this period, as marbleized or “grained” wood mimicked the real thing on mantelpieces. Toothlike dentil molding edged the undersides of mantelshelves supported by consoles.

The Federal period from 1785 to 1825 saw lighter treatments for mantelpieces, as well as for other architectural elements, while the grandiose overmantel of the Georgian era became far less common. The mantelpiece was typically composed of a broad, decorated frieze, or band, below the mantelshelf, with pilaster trim or colonettes at either side of the firebox. It might be made of wood, marble, or a marble look-alike such as Coade stone (an English cast-stone product). Decoration was graceful and slender, with applied neoclassical motifs such as swags, garlands, and urns often set into rectangular or oval plaques in the frieze above the fireplace or in slim, paneled pilasters beside it.

Egg-and-dart, triglyph, and oval sunburst motifs in plaster or wood embellished the mantelpiece. This type of Adamesque ornament, named for the influential 18th-century English architects Robert and James Adam, was as popular in America as it was in London.

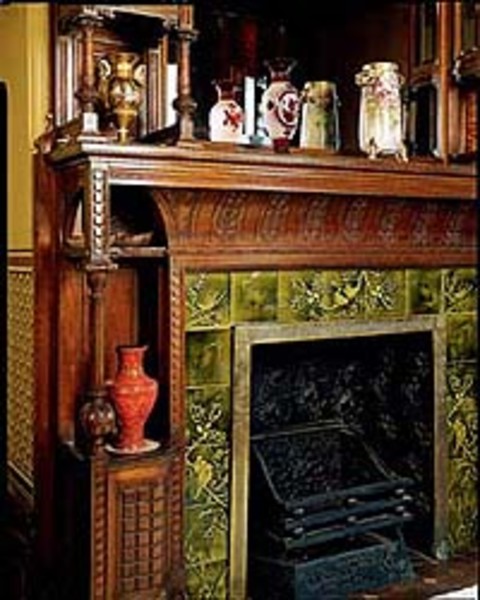

This elaborate, High Victorian mantelpiece at the Flavel House in Astoria, Oregon, has all the hallmarks of its era, from mirrored overmantel and cagelike shelves for ceramics to a mantelshelf, coal grate, and decorative tile surround. Paul Rocheleau photo

In the 1830s and 1840s, Greek Revival motifs included fluted, reeded, or plain columns with blocky bases and capitals. Ornament was bold, rectilinear, and relatively flat, incorporating such familiar motifs as the Greek key design in broad friezes. The construction of mantelpieces echoed the post-and-lintel structural system of the Greek temple, and massive mirrors often replaced the big overmantel of earlier years.

Fireplace surrounds might be of marble or marbleized wood. Black marble with white or cream graining (or, often, faux marble painted on wood or slate) was a favorite mantelpiece material. The best houses, however, were likely to have mantelpieces of white marble.

The 1850s and 1860s ushered in Victorian design influences—heavy arches defining the opening of the firebox and heavy molded paneling of marble or iron on the surrounds. Elaborately decorated iron fireplace inserts were common, and coal grates by now had almost replaced the earlier wood log and andiron arrangement, especially in the East.

After the Civil War, High Victorian design in the Gothic Revival, Eastlake, Aesthetic Movement, and Queen Anne styles brought a truly dizzying panoply of ornament to the American mantelpiece. The towers and columns, brackets, bibelot shelves, and beveled mirrors of the eclectic Victorian era all added emphasis to the mantelpiece—ironically, at the very time central heating was making the fireplace redundant as a source of home heating. Chimney pieces with rounded openings and curving mantelshelves were executed in white marble, faux-painted marbleizing, plain slate, or metal.

A mantelshelf with garniture and a large painting replace the overmantel over the Gothic Revival Tudor arch fireplace at the 1853 Willows in Morristown, New Jersey. James C. Massey photo

At the height of the Queen Anne style the hearth served mostly as a symbol of family solidarity and prosperity. The interest in medieval architecture, decoration, and craftsmanlike values that overcame this intensely mechanical age led to the phenomenon of a Victorian version of the medieval great hall. The stair hall became the site of the grandest mantelpiece the house had to offer, and inglenooks (chimney corners) were in high vogue.

The Arts & Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was an attempt to simplify life and design, and its influence was strongly seen in the mantelpiece. The comfortable inglenook was still important, and in the more open, flowing Arts & Crafts house, it made more sense than in the closed-off rooms of the earlier Victorian years. Beautifully worked hardwood, stone, and brick mantelpieces, usually with simple mantelshelves, featured tiles in medieval or figural patterns or with luminous new color glazes on surrounds and hearths. Copper fireplace hoods, a throwback to early days, were incised with aphorisms exhorting virtue and duty.

Late in the 19th century, there was a tendency to use mantelshelves as the focal point of a room even when there was no accompanying mantelpiece, and even when there was no fireplace! Old fireplaces themselves often became the receptacle for wood- or coal-burning stoves. Many an old house has a mysterious mantelpiece-pilasters, shelves, and all where there was obviously never a chimney, a flue, a fireplace, or—a dead giveaway—a hearth.

In the 20th century, the fireplace continued to serve as a dreamlike emblem of the happy home. Colonial Revival houses relied heavily on the simpler designs of the Colonial and Federal periods, and while mantelshelves and colonettes abounded, there was scarcely an overmantel to be seen. In Prairie School houses of Frank Lloyd Wright and his followers, monolithic brick and stone chimney walls may be of simple fieldstone or glazed brick or tile.

This Wethersfield, Connecticut, example is a typical mid-18th-century fireplace set in a paneled wall with full-height pilasters framing the mantelshelf with a plain overmantel panel.

In the mixed bag of so-called Eclectic Revival styles that dominated between the two World Wars, fireplace openings in “Old English” houses might display the familiar Tudor arch, often in narrow light-colored brick, while those in a Spanish Revival house often had a deliberately crude mantelshelf in heavy, dark wood above a simple rectangular or rounded opening edged with red brick set into a stuccoed wall.

In the 1950s, builders of modern houses frequently made room in tiny postwar living rooms for a fireplace—whose presence was announced on the exterior by a looming chimney on the front wall of the house. And in all the decades since, reproduction fireplaces and mantelpieces have continued to draw builders and buyers as irresistibly as—oh, might as well say it—moths to a flame.