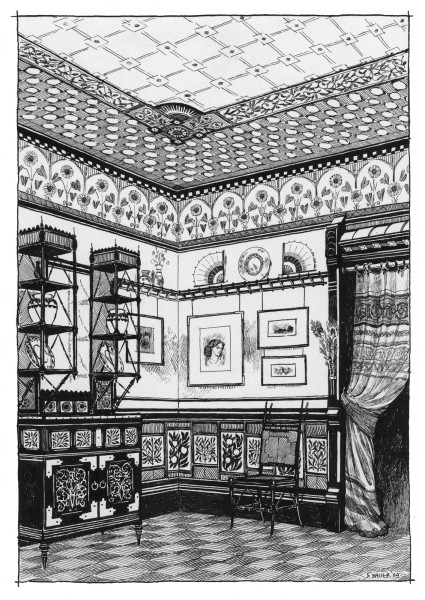

A pen-and-ink drawing by Steve Bauer of Bradbury & Bradbury Wallpapers illustrates the perfect Aesthetic room.

Illustration by Steve Bauer

A reaction against Victorian mass production, precursor to the Arts & Crafts gestalt, the movement of Ruskin, Morris, and Oscar Wilde has been called the “cult of beauty.”

A precursor to British Arts & Crafts reform, the Aesthetic Movement embraced Japonisme, an important coda manifested in the Anglo–Japanese furniture of E.W. Godwin and the decorative designs of Walter Crane and James McNeil Whistler. Popular motifs include the stork, sunflower, and lily. The trend was perpetuated by Liberty & Co. in London and by all fashionable decorators throughout the 1880s.

Names once again famous are associated with this reaction to mid-Victorian “bad taste,” not only William Morris but also ceramist William De Morgan, designer C.R. Ashbee, and tastemaker Bruce J. Talbert. They suggested that the line between the fine and applied arts was false—that the design and manufacture of furniture, ceramics, metalwork, and textiles should rise for the sake of beauty in everyday life. Although Morris often sought to distance himself from the much-parodied Aesthetic Movement (see the operettas of Gilbert & Sullivan), his popular designs actually helped extend its influence in the U.S. By 1870 Morris’s wallpapers were on sale in Boston, and two years later Hints on Household Taste by Charles Locke Eastlake was published in an American edition. The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia followed, bringing thousands of Americans in contact with the “reform movements” in England. Then Oscar Wilde made his famous lecture tour of he U.S. in 1882–83.

In the U.S., New York cabinetmakers the Herter Brothers dabbled in their own version of Anglo–Japanese style by the mid-1880s. Ceramics and silver were widely available in the Aesthetic taste. The Japanesque was of course propelled by the “opening of Japan” by Commodore Perry’s celebrated visit in 1853. Westerners were fascinated by this newly discovered society, uncorrupted by modern machines.

A Hunzinger sofa centers a Manhattan parlor featuring Aesthetic furniture: the table and elaborate cabinets are by the Herter Brothers.

Alan Weintraub

The flat planes, stylized designs, and nature-inspired motifs of the Anglo–Japanese style included storks and owls carved in the backs of chairs, beetles and spiders crawling up the handles of silverware, dragonflies lighting on silver teapots by Tiffany and Gorham, and cherry blossoms in stained glass.

The reformed taste worked especially well in house styles based on vernacular medievalism and the Modern Gothic: Stick Style (called Eastlake in San Francisco), Queen Anne, the Shingle Style, and late Victorian Tudor and Jacobean Revivals. Nevertheless, Italianate and Second Empire houses built in the 1860s and ’70s often were redecorated in the popular Aesthetic taste.

The Aesthetic Movement morphed into Arts & Crafts in England and Art Nouveau on the Continent. In America the craze faded away by 1890, and that last decade of the 19th century saw a nostalgic turn back toward the Rococo, cabbage roses, and mauve. The Japanese influence would continue, more authenticlally, in the work of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright and their Prairie School designs, and in the bungalows designed by Greene and Greene.

The Hallmarks

• STYLIZED, ABSTRACTED ornament was preferred in carving, on walls, and for textiles—flat ornament for flat surfaces. The shaded, realistic depictions of fauna and flora as seen in the mid-Victorian period were out of fashion.

• MOTIFS in the Anglo- Japanese style were popular ca. 1875–1885: cranes, swallows, bamboo, and cherry blossoms. Motifs and palettes were based, too, on medieval and Gothic designs. An alternate name for Aesthetic and Eastlake is Reformed or Modern Gothic.

• WALL TREATMENTS embraced the tripartite division of dado, fill, and frieze. The fill was kept simple—even done in one color in the Japanese fashion—to set off framed prints hung from the picture rail. Wall and ceiling papers often had oriental motifs.

• TERTIARY COLORS—olive and sage, ochre, terra cotta and russet, peacock blue—were favored, a palette influenced by William Morris’s revival of medieval formulas, and by the subdued but clear tones of Japanese woodblock prints.

• EXOTIC TASTES An Exotic Revival was a sub-theme peaking around 1880 with the American fascination for Arabesque ornament. Moorish tiles, Persian furniture, and Turkish smoking rooms were all the rage.

In the Connecticut Queen Anne, wall decoration of 1882 was re-created for an Anglo–Japanese room with rare furniture by British architect Thomas Jeckyll; the new mantel is in his style.

Edward Addeo

Aesthetes and Philistines

By the mid 1870s, “Art for Art’s Sake” assumed the proportions of a national mania in England. No longer dependent on serious-minded medievalists like Morris, the movement was whipped to a frenzy by a younger and outrageous band of long-haired, ultraelegant Aesthetes, as typified by Oscar Wilde. The Cult of Intensity, also known as the Aesthetic Craze, came into full flower with its own symbology—the sunflower, lily, and peacock—and startling new modes of dress and behavior.

To be aesthetic was not merely to appreciate Art, but to become of oneself Artful. Not just Artful, but visibly, soulfully, utterly Artful, a chalice of exquisitely intense feeling. The most popular expressions of the era used the word “too,” indicating that whatever was being experienced or described was simply too exquisite, too refined, and too Artful to be conveyed in mere words: It was simply TOO! Utterly TOO! Consummate too too!

The opposite of the Aesthete was the Philistine, those who were crude, devoid of culture, bound by the material, and tied to the common. “Common” was the ultimate Aesthetic insult. Gilbert & Sullivan were accused of being Philistines when they premiered their operetta “Patience” (1881), a parody of the Aesthetic Movement:

Eastlake interiors were the geometric, wood-rich variant of Aesthetic in the U.S.

Douglas Keister

Audiences were, however, enraptured by the beauty of Aesthetic costume. Increasing numbers of women happily exchanged their uncomfortable whalebone corsets , tight bodices, and heavy skirty for light, flowing Grecian gowns, sleeves puffed at the shoulders in the Aesthetic mode. —Bruce Bradbury, 1984

Interior Visits

18 STAFFORD TERRACE, the Linley Sambourne House, London, 1875. Morris wallpapers, Eastlake furniture, ebonized overmantel, Japanese prints, and stained glass. rbkc.gov.uk/museums

CHATEAU-SUR-MER, Newport, R.I., 1852, remodeled 1870s by architect Richard Morris Hunt. Billiard room and stairhall are in Eastlake style, two main bedroom suites are done in superb English Aesthetic taste, and there’s an exotic Turkish room. newportmansions.org

EMLEN PHYSICK ESTATE, Cape May, N.J., 1879, architect Frank Furness. The asymmetrical Stick Style house has strong geometry and surviving Aesthetic/Modern Gothic interiors with much of the original furniture. capemaymac.org/emlen-physick-estate

EUSTIS ESTATE, Milton, Mass., 1878, architect William Ralph Emerson. Stone English

Queen Anne house with Modern Gothic details, rich woodwork, stained-glass windows, trussed ceiling, metallic-paint wall treatments. historicnewengland.org

GLESSNER HOUSE, Chicago, 1887, architect H.H. Richardson. Furnished with goods from Morris & Co.; tiles designed by John Moyr Smith tell the story of Lancelot and Elaine; “art” furniture is by Isaac Elwood Scott. glessnerhouse.org

In an 1882 Connecticut Queen Anne, the sophisticated music room has ebonized woodwork recalling lacquer.

Edward Addeo

GREEN DINING ROOM, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, decorated by William Morris with Philip Webb and Edward Burne-Jones, 1867. Elizabethan and Gothic Revival motifs, highly decorated. vam.ac.uk

MARK TWAIN HOUSE, Hartford, Conn., 1874, architect Edward Tuckerman Potter, redecorated 1881. A world-class Aesthetic interior by L. C. Tiffany’s Associated Artists with work by Candace Wheeler. marktwainhouse.com

OLANA, Greenport, N.Y., 1872, architect Calvert Vaux, decorated by Frederick Church. Exotic Persian Revival house of the landscape painter; intact color scheme and Middle Eastern stencils by the artist. olana.org

PEACOCK ROOM, Freer Gallery, Washington, D.C., decorated by James McNeil Whistler, 1877. Moved from London, a great surviving Aesthetic interior in Anglo–Japanese style. Intense color, gold leaf. freersackler.si.edu