Besides the table lamp and early gas-electric fixture, the mood at the Babcock House in Michigan comes from natural light orchestrated by the art glass sashes, as well as roller shades and curtains. (Photo: David Yarnell)

The artistic interiors of the late 19th century were admired in their day—sometimes with a bit of awe—as dark dens of high taste. The ornate rooms of these Queen Anne houses, Richardson Romanesque castles, and Shingle Style cottages—all part of the Aesthetic movement—were indeed dark by 21st-century standards, jaded as we are by decades of cheap electricity, but amid the dusky ambiance, Victorian eyes saw sparkle and glow. The progressive designers of these houses took advantage of new materials and technologies, as well as many old ones, to regulate and direct light in subtle ways to enhance décor and add artistic effects. For example, more affordable, mass-produced glass meant larger windows and more of them, while modern, open floor plans that connected all the principal rooms to a central hall by wide doorways could be lit by tall windows on the staircase. People, air, and especially light circulated with new freedom in these spaces, producing magical results right in step with the Aesthetic movement’s motto of art for art’s sake.

John La Farge revolutionized stained glass with windows like Peacock & Peonies, which used new kinds of glass and techniques such as plating (double thicknesses of glass).

The Challenge of Abundant Light

After dark, Victorians enjoyed more lighting options than any society before them. Starting in the 1850s, the Industrial Revolution introduced progressively brighter and more user-friendly sources, first from oil- and gas-burning lamps and then, for a few households, from electricity. These were big changes, and each breakthrough was challenged by a chorus of tastemakers who reacted to the shocking leap in quantity of artificial light. Writing in The Drawing Room, Its Furniture and Decoration (1877), Lucy Orrinsmith recommended that light should be educated to accord with indoor life, while Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, authors of Decoration of Houses (1902), noted that nothing had done more to vulgarize interior decoration than the general use of gas and electricity. The proper artistic reaction was to housebreak this flood of light with an assortment of decorative tactics.

By far the most powerful source of light in the artistic era was the sun, and to temper it, the homeowner modulated the large windows of the era with an impressive array of treatments: curtains, shades, blinds, and awnings. Welcoming the dull, grey light of a winter afternoon meant pulling all curtains wide open; staving off the fierce summer rays that heated rooms and destroyed fabrics required pulling down roller shades and awnings. Pale shade tints like ecru and sage would diffuse a subtle, cool light, but, as one writer warned, homeowners needed to be wary of red shades that created a descent into the Inferno at every afternoon tea. Lace curtains were popular for casting delicate patterns, while more adventurous decorators sought out shades made of printed Indian muslin or embroidered their own designs on linen.

The artistic era also transfigured sunlight with the glass itself. The stained-glass windows of masters like John La Farge and Louis Comfort Tiffany are legendary, but there were many other brilliant designer-artisans, such as Charles Booth and Mary Tillinghast, who custom-crafted windows in studios from unique designs. Most leaded and colored-glass windows, however, were mass-produced in large workshops from stock patterns that could be ordered by mail. Called art glass windows, these panels appeared in transoms (over large, clear glass panes), stair halls, or any place that called for light but an obscured view, like bathrooms or side windows facing a nearby house. Folding, stippling, layering, and otherwise adding texture to colored glass gave it special optical effects—both realistic (like draped cloth) and abstract (such as patterns of colored light)—while limiting light transmission and visual clarity.

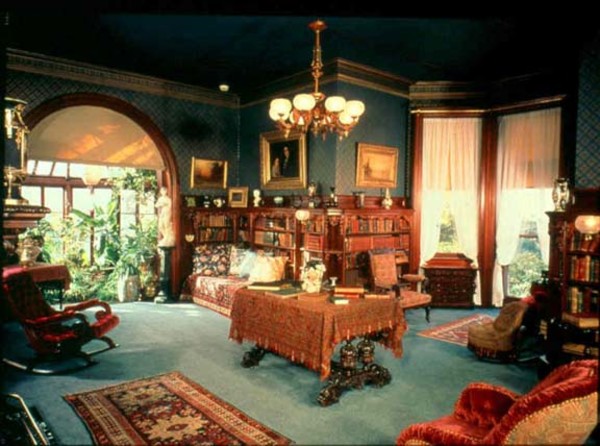

What better template for Aesthetic décor than this 1881 Interior-Morning Room by Louis C. Tiffany, showing systems of curtains for regulating light, as well as stained-glass transoms. (Illustration: Karen Zukowski collection)

Patterns on the Walls

In the Aesthetic room, even décor was arranged with light in mind. For example, the three-part decorating system so characteristic of the time divided a wall into a dado, panel, and frieze. This tripartite scheme typically put darker colors and bolder patterns at the base of the wall (the dado or wainscot), while leaving the lightest, most delicate patterns at top (the frieze). In this way, light attracted the eye to the upper zone of the room, making it appear taller. Adding metallic colors to wallpaper and stenciling reflected even more light, creating a filigree over the basic patterns and colors that emphasized the planar quality of walls and ceilings. A good example of the power of this decorative device appeared at the library of the Mark Twain House, designed by the premier Aesthetic firm, Louis C. Tiffany and Associated Artists. When restorers moved the ceiling fixture back into its original, off-center position in the 1970s, they discovered that it illuminated the gilt stenciling on the walls more evenly, making the space more coherent and giving the walls a smooth shimmer.

By the end of the 19th century, when up-to-date suburban homes were heated with furnaces or stoves, age-old technologies took on a new lighting role. Though fireplaces were no longer essential for warmth or cooking, they put on an artistic light show as wood fires flickered or coal fires radiated a steady, soft glow, each giving the room a strong orange tone. In the same way, homeowners who could afford much better used candles year-round to enjoy the soft, yellow light that seemed to slow the pace of life.

At Sagamore Hill, the home of Theodore Roosevelt from 1887 to 1919, the dining room is lit with gas sconces, now electrified, that simulate what was considered a huge amount of light in the late 19th century, even during the era of early electric lighting.

Let There Be Light

In an age that opened up new options in artificial light, the odds are that more people used oil lamps than any other source. Though some folks continued to favor older oil types (including spermaceti, refined from whale oil; colza, from the seeds of the rape plant; and camphene, a cheap but volatile mixture of turpentine and alcohol), for most households, kerosene offered the right combination of price and quality. The kerosene age began in 1859, with the first oil well in Titusville, Pennsylvania, and time brought improvements, such as burners with more aeration, the double-wick system, and purer oils. By the end of the 19th century, the light from one kerosene lamp could be as much as 50 times brighter than one candle. All oil lamps gave a pure white-yellow light and, if maintained properly, not too much smoke or smell.

By the 1870s, the households in most cities could tap into municipal gas systems to take advantage of gas lighting as well oil lamps, candles, and firelight. Gas traveled through rigid piping, so fixtures had to be attached to walls and ceilings, though a small lamp could be fed by a rubber hose attached to the fixture, making it portable to limits of its tether. The advantages of gas were obvious: bright light at the twist of a cock. The disadvantages, though, were insidious.The byproducts of gas lighting were notoriously smoky and corrosive, tarnishing silver and decaying cloth. Most municipal supplies fluctuated, and if each burner was not carefully monitored, gas might leak and put the entire household at risk of death by asphyxiation or explosion. As a consequence, many houses relegated dirty, smelly gas lighting to areas where its drawbacks were outweighed by its utility: hallways, vestibules, kitchens and other service areas. Surprisingly, this included the nursery, where candles and kerosene were considered even more dangerous than gas.

Wallpaper with a metallic diaper pattern defines the library at the Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut, a landmark example of Aesthetic decorating. (Photo: Courtesy of Mark Twain House)

A typical gas burner produced as much light as several candles, but it came with a glaring, unflattering spectrum that made people look wan and caused color shifts in interior décor. An 1885 decorating manual warned that yellows would look dull and gloomy, greens tended to be pale and monotonous, blues and blue-greens might turn blackish, and red tones would change the least. To counteract this hocus-pocus, the manual advised decorators to select wallpapers by both gas light and natural light.

By the end of the century, most Americans had read about the wonderful new phenomenon of electric light, and some had even seen it operating at great industrial fairs or on the shopping streets of the country’s biggest cities. A few wealthy technophiles like J. P. Morgan installed systems in their mansions, and by 1882 a small, experimental system supplied businesses in lower Manhattan. Nonetheless, the requirements for full conversion to electricity were stiff: a utility capable of providing a reliable supply, and technicians who had mastered the mysterious science of wiring and voltages. On top of this, the first lamps or light bulbs developed by Thomas Edison incorporated carbon filaments that, when energized, resembled red-hot hair pins. These lamps delivered a dim, amber light that, while steadier than an open flame, tended to cast strong shadows through the clear glass envelope. Early electric light fixtures often had no shades at all, but as designers realized the freedom of the new technology, they explored its decorative possibilities. Electric fixtures didn’t need to vent heat or fumes, so the light source could be almost fully covered in a translucent dome of colored glass or mica.

Crude as it was, early electric light posed a threat to gas lighting, so, to protect its market, the gas industry literally cleaned up its act. They introduced new fixtures fitted with Welsbach or Auer mantles that burned brighter light with less heat. Some fixtures had smoke shades (little soot-catching umbrellas suspended over the mantle), while others vented fumes to the exterior. By the 1890s it was possible to hedge your bets by installing combination gas and electric light fixtures powered by both sources that could fall back on gas when the electricity failed. For most households, however, electric light did not become a reality until the first decades of the 20th century.

The huge dining room at Kingscote in Newport, Rhode Island, is part of an 1881 addition by Stanford White. Its rich textures come from sources as varied as Italy and the Orient, but the centerpiece is a wall of opalescent glass tiles and bricks by Louis C. Tiffany & Co. (Photo: Courtesy of the Preservation Society of Newport County)

Whether fueled by oil or gas, both kinds of lamps were customized to their uses. Multi-burner hanging fixtures were designed to cast general light, while substantial tabletop lamps provided task lighting. If gas brackets were not installed in vestibules and hallways, people carried small oil lamps or candles about the house to light the way. All of these were produced in a variety of decorative forms, and a homeowner with artistic interiors could choose a suitable fixture in one of the new styles like Modern Gothic or Japonesque.

Gas lamp shades and reflectors set the lighting tone for the whole room. The ceiling fixtures that supplied most of the light were usually fitted with frosted or cut-glass shades to moderate the glare of the flame without diminishing the light. Many shades were tinted to coordinate with room décor or improve ambiance. Blue, for example, counteracted the unnatural spectrum of the gas flame, while pink flattered complexions. Lamps with flames anywhere near eye level, like those over the dining table or on a desk, often had shades with a bright white interior casing, or a dark, opaque shade that might be painted, pierced, or otherwise decorated. These shades protected the eye from the naked flame and cast a pleasing glow and pattern, while simultaneously focusing light downward.

When it came to special lighting effects, Aesthetic interiors were as inventive as Hollywood movies. Tables, chairs, and plant stands stood on mechanistic legs and arms of shiny metals like brass, nickel-plated steel, and copper. On top of this, the metals might be patinated in wild tones that would glimmer from dark corners. Mirrors were framed in metal or gilt wood, and furniture was inset with brass stringing, ceramic plaques, mother-of-pearl, and lacquer panels, and fitted with metal hinges. Textiles interwoven with spangles or silver and gold threads would shimmer by the light of a coal fire. Even firescreens became opportunities to enhance firelight when they were fabricated from stained glass or wire mesh embellished with silhouettes. With so many reflective surfaces, an artistic room could almost generate its own light.

No one relies on oil lamps or gas lighting anymore, but there remain many ways to conjure up period artistic effects in a late 19th century house. Dress windows with decorative shades—or even pressed flowers and ferns—that cast creative shadows. Emphasize the planarity of walls and ceilings with metallic patterns on papers and stencils that make the most of distinctive architectural features. Reduce the wattage on electric light fixtures. Then light a fire and a few candles and spend an artful evening watching the flames make the walls shimmer.

Karen Zukowski is author of Creating the Artful Home: The Aesthetic Movement; past curator of Olana, the Frederic Church home; and a house museum consultant.