Just as in the past, Rookwood continues to produce hand-painted and -glazed art tiles.

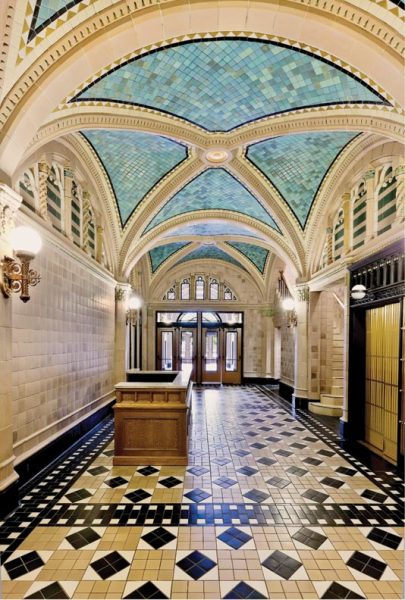

When Rookwood Pottery embarked on a restoration of Chicago’s Monroe Building in 2010, history repeated itself. As part of the building’s overhaul, Rookwood had been tasked with replacing its floors with new architectural tiles—in effect, restoring the work of the Rookwood artists who had first installed them a century earlier. And when Allan Nairn got up close with the work of his forebears, he marveled at craftsmanship that transcended time. “The job was so complex—the angles, the moldings in the corners,” says Nairn, Rookwood’s art director. “You can’t help but have amazing respect for the people who did that work.”

First founded in 1880, Rookwood Pottery grew from the pet project of a woman of leisure into a world-renowned business whose vases, pots, and artisan tiles became sought-after treasures for their elegant simplicity and hand-painted adornments. After languishing for much of the post-Depression twentieth century, the Rookwood name survived thanks to the efforts of a Michigan dentist. But ever since a group of investors restarted the brand in 2006, the Cincinnati-based company has recovered its past glory, tripled its workforce, and expanded its output—without losing track of the company’s deep history.

When well-to-do Maria Longworth Nichols visited the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, she marveled at works of sculpture and pottery from around the world. She had been trained as a painter and fostered a love of ceramics during a time when America was regarded as an artistic backwater. Using money from her father and drawing inspiration from her trip to Philadelphia, Longworth Nichols sought to change that perception by starting a pottery shop on Eastern Avenue and hiring notable artists of the day. Rookwood Pottery produced its first pieces in 1880. The RP emblem imprinted on the bottom of each piece—accompanied by flames or Roman numerals, depending upon how long after the company’s founding the piece was created—became a calling card.

Rookwood Pottery was involved in the restoration of Chicago’s Monroe Building, replacing all the flooring with new tiles.

In particular, Rookwood tiles found their way into homes around Cincinnati and destinations beyond, like Grand Central Terminal, the Union Trust Building in Detroit, and the Seelbach Hotel in Louisville, Kentucky. On the international circuit, the company won awards for its pottery at the 1889 Paris Exposition Universelle, the 1901 Exposition International de Ceramique et de Verrerie in St. Petersburg, Russia, and others. The company’s popularity coincided with an appetite for luxury goods enabled by early twentieth-century prosperity. “Back then, that was a novel concept: ‘We don’t need these vessels, we don’t need these pots, but we want to show that we can finally afford something other than just our basic needs,’” says Martin Wade, who co-owns Rookwood Pottery.

But the dawn of the Great Depression—and its impact on luxury goods—signaled the start of Rookwood’s decades-long decline. After posting a series of losses, the company declared bankruptcy in 1941 and limped along into the 1960s before shutting its doors. But especially around Cincinnati, Rookwood’s reputation survived. “Rookwood was this mythical thing out there, this concept. Everybody talked about Rookwood, but it wasn’t alive,” Wade says. Rookwood pieces were collector favorites. In 2004, a Rookwood vase by artist Kataro Shirayamadani set a record when it sold for $350,750 at Cincinnati Art Galleries.

In 1982, Dr. Arthur Townley, a dentist from Michigan and Rookwood collector, purchased the company’s original trademarks and all of its assets to prevent the brand from heading overseas. Two decades later, a group of investors that included Wade purchased these assets from Townley and returned Rookwood to its Cincinnati roots.

Socialite Maria Longworth Nichols started Rookwood Pottery in 1880.

And after a rocky start, Rookwood Pottery is in a state of resurgence in its three-story, 90,000-square-foot headquarters on Race Street. In recent years, its 20-person staff has grown to roughly 50. It has doubled its number of skutt kilns from four to eight, along with electric and gas kilns. Rookwood employs a seven-artist team led by Nairn, a Brit and former graphic designer who learned to throw pottery in the Scottish Highlands before coming to the States in the early 1980s. The company’s stock and trade—tiles, moldings, liners, and art pottery—is the same as ever. And business is going great: A recent commission for 18,000 tiles at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Monona Terrace Community Convention Center in Wisconsin represents about five percent of this year’s output, Wade says.

A cornerstone of this resurgence is the treasure trove of source material from Rookwood’s first incarnation: production notes, glaze recipes, sketches from the company’s early artists, and some 3,500 pottery molds, all of which have been cataloged for easy retrieval. Today’s Rookwood artists have on occasion recast new molds from these antique originals and adapted them into new products. The Heritage Collection is a line of art tiles that draws heavily upon this archive, and the result is timeless. “You can’t tell when they were designed—they looked contemporary today,” Nairn says of the collection. “And we’ve got [original] tiles out of the 1912 catalog and the 1925 catalog that you would swear were designed a couple of years ago.”

Many of the company’s tiles are created from original molds.

A Bridge Between Tradition and Modernity

That’s not to say Rookwood is recycling its past to the detriment of its future. Two other lines of tile—Timeless Beauty and Modern Classics—evoke a bridge between tradition and modernity. At any given moment, the artists have dozens of new pieces in experimental production. Modernity appears in other ways as well: Recently, the company began offering lines of 3/8″-thick tile alongside its 5/8″-thick tile to conform to modern standards. The company uses a variety of twenty-first-century advantages, from computer programs that render concepts for pottery molds to iPhone apps that remotely monitor kilns during busy firing schedules.

Still, the human touch remains. Every tile, vase, bookend, and other piece of pottery is hand-painted and -glazed, using the concoctions of elements blended by Rookwood’s glaze chemist Jim Robinson. A human hand touches every piece “at least 15 times,” Wade says, and that hands-on approach means each piece is unique. “When people come to us and say, ‘I want these to look exactly alike,’ I tell them they might as well go to Walmart because we can’t give it to them,” he adds.

Modern-day Rookwood Pottery is at an intersection—constantly looking toward the future, always reverent of the past. That reverence is something Nairn feels every time he touches a mold created by one of the Rookwood artists that came before him. “You definitely get a feeling from the fact that somebody did this a long time ago, and that it still has relevance today,” Nairn says. “You have respect for that person. And you treat that object with the respect it deserves.”