Decorative metal ceilings were first used in formal parlors and living rooms as an economical alternative to decorative plaster. (Photo: Michael Jackson archives)

A popular choice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for both residential and commercial buildings, pressed tin-coated steel ceilings made an elegant, economical addition to many rooms. Early steel manufacturing companies cited the practicality of this material over wood and plaster, touting it as “perfect protection against fire, water, dust, vermin, and rodents” as well as advertising the metal as not “cracking, peeling, or shrinking.”

Up until World War I, when manufacturing was diverted to war efforts, the same process was used to make sheet metal for roofing ornament and skylight casings-even children’s author L. Frank Baum created a character out of tin in his 1900 novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Dramatic, deep-paneled steel ceilings could be found in high-society townhouses, while simpler patterns were found in more modest homes. We’ll look at old and new technologies used to re-create this historical ornament.

Sheets of steel are still hand-cut with shears at W.F. Norman. (Photo: Lee Ann Russell)

Tin Ceiling Origins

Historian Ken Postlethwaite explains that although there is some controversy over where the first pressed metal ceilings popped up in this country, it is believed that their use began in 1885 with the experimental installation of tin-plate squares used to patch a ceiling in Brooklyn, New York. Rope was used as a molding to cover the joints, and the corners were hidden by wooden rosettes. By the late 1800s, there were about two dozen factories pounding out tin-coated steel ceilings and sidewall.

“One reason for their popularity was cost,” explains Bill Perk, Jr., president of the contemporary tin ceiling manufacturer M-Boss, Inc. “Decorative plaster ceilings were expensive because a master craftsperson would need to be employed to do the work-a homeowner could get a similar effect with pressed-metal ceilings at a fraction of the price.” When metal ceilings were painted white, they looked like expensive, ornate plaster.

They were also sold as the modern choice for ceilings. In the 1910s, Canton Steel Company advertised its steel ceilings as an effective treatment in the living room of a modern home as well as in an up-to-date kitchen. The material was also used as wainscoting and sidewalls in bathrooms and libraries. With improved machinery through time, companies were able to produce a higher-grade product at a more reasonable price.

Past Presses

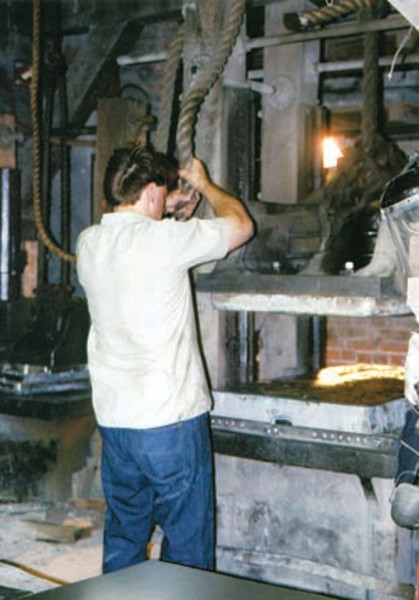

A rope-drop hammer stamps out decorative “tin” ceilings at the W.F. Norman Company. (Photo: Lee Ann Russell)

In 1900, hand-operated machinery was used to mass-manufacture metal ceilings. Much like the process of repoussé, in which metal is stamped from behind with hand-held hammers to create a decorative pattern, ceiling panels were individually stamped by mechanical drop-rope hammers using dies. Dies were placed in a press with the female half set onto a cast-iron bed and the male half attached to a large cast-iron hammer hanging above the press bed. A sheet of steel was then placed over the die on the cast-iron bed and a press operator released the hammer to drop onto the bed, stamping the design into the metal by force when the die sets met.

One company that reproduces steel ceilings using these old methods is the W. F. Norman Company, a 106-year-old sheet-metal factory in Nevada, Missouri. Resembling a medieval torture chamber more than a metal manufacturing shop, the company’s cavernous 1910 brick building is filled with antique contraptions such as its six original drop-rope hammers—similar to those used to make suits of armor in 17th-century France—plaster-of-Paris molds, 900-pound cast dies, and old shears and brakes. Fan belts whir as a rhythmic thump, thump, thump stamps out the tin-coated steel panels into 140 original decorative patterns ranging from Rococo, Gothic, Empire, and Colonial.

In 1979, C. Robert Quinto purchased the shop, which had been in business since 1898 and in its current location since 1910. He intended to start a wood-burning-stove company, but once he spied the tin-ceiling presses that had stood silent for 60 years, he dusted off the old relics and put them back into service. Today Robert’s children, Neal, Mark, Sue, and Chris, run the business. “The metal used is similar to metal used to make coffee cans,” says Neal Quinto. More malleable than steel, zinc is also used when the relief of the design must be deep and sharp.

An original 1898 plaster of Paris mold from W.F. Norman. (Photo: Lee Ann Russell)

If a sample of a historic pattern has survived in relatively good condition, W. F. Norman can repair it and use it as a three-dimensional model for casting new dies. Since cast iron will shrink in casting as it cools from a liquid to a solid (approximately 3/16″ per foot) a new die set will create a pattern that is slightly smaller than the original.

Modern Methods

Today many pressed-metal shops are run with automated hydraulic presses. M-Boss, Inc., one such company, stamps metal sheets into decorative patterns with 480,000 pounds of force. Many of the designs M-Boss creates are based on historical patterns that Bill Perk has found. The majority of ceiling panels are made of aluminum because it is rust-free and lightweight—less than a pound per panel. Whether old or new technologies are used, these ceilings are made to last. W. F. Norman’s offices still have the original tin ceilings. “Without water damage they can last forever,” says Quinto.