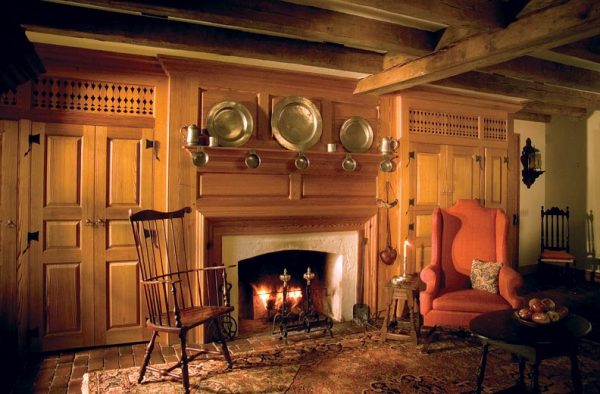

For a new old house in New York, architect Gil Schafer replicated this original mantelpiece and placed both in the living room. (Photo: Eric Roth)

Fireplaces have been integral to the American home since settlers built their very first structures, and have evolved over the years from sprawling, multifunctional necessities to refined showpieces of craft and design. At heart, they are pure function, but on the outskirts, all form.

Determining appropriate new old fireplaces and mantelpieces requires investigation on multiple fronts: architectural trends, cultural precedence, and material availability. A historic fireplace tells a story about a home’s inhabitants and their origins, whether stone or marble was quarried nearby, or which designers were in vogue at the time. A successful new old version should do no less.

Evolving Standards

The first permanent American homes were one room, sometimes with loft spaces above. Fireplaces began as hearths centered in this “hall,” with smoke funneled outside by either holes in the roof or short wooden chimneys. Spark protection amounted to hearths and back walls (called “reredos”) made of local stone. Without jambs, these early versions were inefficient and unable to direct heat into a room or prevent smoke from blowing crosswise. Eventually, fireplaces migrated and were built into walls or outside; their jambs often were faced with heavy hewn timbers with massive lintels in between.

Since these more rustic beginnings, fireplaces and their mantelpieces have evolved over the centuries, typically in relation to the aesthetics of an era combined with the European influences of a particular region. As Henry J. Kauffman writes in The American Fireplace: “Chimneys, fireplaces, and mantelpieces are intimately interrelated…Such facilities, long used and fondly remembered from their homelands, were copied by the English, Dutch, Swedes, and Germans for their first permanent dwellings in America.”

Architect John Milner specializes in restoration projects, as well as designing new homes that reflect the traditions of American architecture. Based in southeastern Pennsylvania, he is privy to a rich collection of vernacular architecture created by diverse settlers. In order to help restore some of the region’s earliest homes, he traveled to the builders’ original areas. “It was fascinating to discover that a wood mantelpiece I saw in a pub in Cornwall, England, was remarkably similar to the mantelpiece in a 1714 house in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania,” he explains of the correlation between Old and New World construction.

Architect John Milner replicates colonial-era mantels for many of his Pennsylvania designs.

As houses grew more sophisticated with more rooms, the number of fireplaces increased, creating the opportunity for variety. Architect Gilbert Schafer of G.P. Schafer Architect in New York explains: “It is a measure of the settlers’ design sophistication that mantelpieces would not be identical from room to room.” Typically parlors boasted the grandest designs, followed by dining rooms and master bedrooms. Second-floor fireplaces were common with improved construction techniques and tended to be smaller and less ornate.

Kitchen fireplaces were usually generous in dimension, oftentimes between 6′ and 9′ long and 4′ or 5′ high, with 3′ of depth. Built in the seventeenth century, a kitchen fireplace would typically be made of stone, with wooden lintels and without mantels or ornamentation. In the late seventeenth century, ovens were added to the back wall, typically placed to one side but occasionally centered. Even as mantelpiece ornamentation increased in the early eighteenth century, kitchens fireplaces changed very little.

Gil Shafter incorporated delicate details in a mantel for master bedroom. (Photo: Eric Roth)

As European medieval characteristics gave way to Georgian features, craftsmen began to treat fireplace walls with paneling, which were usually of various shapes and sizes, their general arrangement tending toward asymmetry. Often, entire walls were paneled, with cupboards and doors included.

Various architectural styles, including Georgian, Federal, Neoclassical, Greek Revival, and Victorian, made their marks throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Marble, a particularly elegant facing that could be quarried in America or imported from Europe, was incorporated more frequently in the latter eighteenth century, as were mantelshelves. Wealthy merchants and landowners, often influenced by designs seen in books or along trade routes, afforded the best designers, carvers, and plaster molders of their time, creating some of America’s most spectacular showpieces.

Working with Established Traditions

Whether a new old homeowner desires a Federal-style mantelpiece with molded ornaments or a Dutch-style design with painted tiles, a specific look can be achieved with either reclaimed or newly built mantelpieces. Milner encourages both avenues, while cautioning that historic finds must work with the project’s architectural story. “I like to incorporate preserved mantelpieces the way they would have existed originally, to treat them as part of the architecture and not as just found objects. It needs to work,” he explains. Schafer adds that deciding on a reclaimed mantelpiece before construction is helpful for two reasons: It can affect a room’s overall molding characters and also determine the firebox dimensions.

In his own home, John Milner used a simple, unadorned mantelshelf for an early American look.

Milner’s own Pennsylvania home, the 1724 Abiah Taylor House, exemplifies eighteenth-century English Quaker style, including the parlor’s mantelpiece of bolection molding topped by a mantelshelf. For an addition, however, he drew plans for a new old fireplace “based on the precedent for simpler designs.” Its firebox of stone is surrounded by white plaster and topped by a salvaged antique mantelshelf. “I exercised a little creative license and went with the French raised hearth with supporting limestone brackets,” he says.

Schafer agrees in the potential for creative variances here and there, particularly since “new old houses can express that feeling of having grown over time. It’s not outrageous to think that a successive generation might incorporate a mantelpiece that worked in their period,” he explains.

No matter the decade, a fireplace afforded the opportunity for many craftsmen—carvers, potters, marble cutters, and more—to exercise their trades. Not unlike a front door or china collection, a high-style fireplace symbolized an owner’s wealth and prestige. But while one design greeted guests in a parlor, another baked bread in the kitchen while yet another warmed an attic bedroom. Often beautiful but always utilitarian, fireplaces are ubiquitous throughout architectural history and are just as pivotal in new old homes today.

Interested in other fireplace options? Learn how to make the most of a freestanding fireplace.