Yards were zoned for adults and children, amusements, entertaining, and eating.

Ernie Braun/Eichler Network Archives

New materials and construction methods marked the postwar era of the mid-20th century. An exploding population and prosperity led to a building boom, mostly in single-family houses built in the burgeoning suburbs.

No other builder/developer of the time was as prolific as California’s Joseph Eichler. His modernist houses, stunning in appearance and efficiency, bear little relation to the postwar ranches and Capes thrown up nationwide. Eichler’s success came from his ability to combine progressive community planning, consistent architecture, and innovation to offer exceptional houses at a reasonable cost.

Eichler was a businessman and real-estate developer, not an architect. Yet it was he who insisted that the houses be modern, even if acceptance was slow in coming. He believed in the innovative architecture and the lifestyle it promised. His California Modern is a residential, outdoors-oriented adaptation of what had been largely an institutional and commercial style. The family-oriented houses had flat or low-slung gabled roofs, few windows on the street side, and open plans.

Eichler started out in 1947 with prefabricated houses sold to owners who would build on their own lots. Unsatisfied with that approach, Eichler bought 45 acres to develop in a consistent manner. At first he used a draftsman to design the houses, but soon hired the modern architects Robert Anshen and William Stephen Allen, and was on his way.

From 1950 until 1967, Eichler worked with celebrated modernist architects including Claude Oakland, A. Quincy Jones, and Frederick Emmons. Always, the designs were modern. Eichler was quoted as saying: “Many builders say ‘give the people what they want,’ but how can people ‘want’ innovations they have never seen or heard of?” Eichlers were among the first development houses with large glass sliders, built-in appliances, metal cabinets, and radiant heat in the floor.

Overextended on far-reaching projects including low- and high-rise urban housing and co-op communities, Eichler Homes filed for bankruptcy in 1967. Joe Eichler continued to work on innovative housing until his death in 1974.

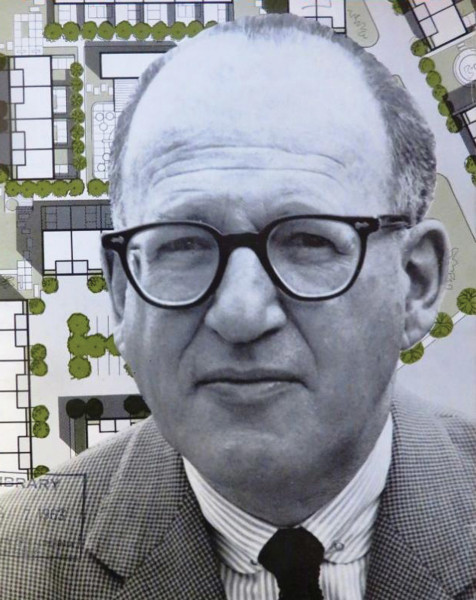

Joe Eichler

1963 American Builder Cover Courtesy UC–Berkeley

What has made Eichlers worthy of cult status? It’s not only the rekindled interest in Mid-century Modern design. Beyond the low-slung geometry and glass walls, Joseph Eichler had offered innovation, variety, high-quality construction, and livable communities.

New for the times were such Eichler trademarks as exposed post-and-beam construction, board ceilings open to the roofline, and slab floors with integral radiant heat. Eichler introduced a master bath in 1953, which soon became a standard feature for three-bedroom homes. Later models have an atrium at the entry. In the mid-1960s, the large, glazed center gable became an Eichler signature.

The houses make best use of small lots, concentrating outdoor space in the rear, contiguous with open living space. Bedrooms are in front; high clerestory windows keep them private, as do the flanking carport or garage and walls.

Although they went up quickly to meet demand, Eichlers were designed with rare attention to detail. With open plans, paneled walls, and exposed beams, costly wood trim and plastering were unnecessary. The inherent design of the houses made them affordable, even fitted out with expanses of glass and redwood. Nor were these cookie-cutter homes. Designs evolved, floor plans changed, carports and garages were added, atriums, patios, and terraces introduced.

Then there was the commitment to creating diverse, middle- and mixed-income neighborhoods. Coveted California Eichlers go for big bucks now, but the streets of Eichler neighborhoods remain appealing. Varying site layouts, façades, and rooflines keep the tracts interesting.

MCM outside of California: oldhouseonline.com/house-tours/postwar-mid-century-modern-communities

Joe Eichler was asked what label he gave his homes: contemporary, modern? “I call them Eichler homes,” he answered. “There’s nothing else like them.”

That wasn’t entirely true. Other architects were working in a similar vocabulary; in fact, the modernist architects who designed for Eichler Homes pursued other commissions, using the same principles if not signature elements. Besides, postwar houses were designed to be replicated. Architects even published articles for homebuilders to encourage adoption of modern ideas. There’s a name for the non-Eichlers: they’re called Likelers. It’s not necessarily a pejorative term. Most are decent builders’ versions of Contemporary designs, including those of Eichler Homes. Others are architect-designed.

Residents regularly report that their Eichler homes “live bigger than they are,” despite a relatively modest square footage. An underappreciated trait, modesty all but defines these homes.

A typical Eichler model features a broad, low gable and recessed entry.

Courtesy Gibbs Smith

Birth of MCM

Frank Lloyd Wright With a career spanning 70 years, Wright (1867–1959) was a pioneer in the proto-modern Prairie School of architecture in the years 1900–1914. Lacking historical ornament and motifs, these houses are low and horizontal with ribbon windows. In the mid-1930s Wright developed the concept of the Usonian house—modern, moderate in size, featuring concrete-slab construction and a nearly flat roof, with open living space and small, sequestered bedrooms. Widely published, and designed for a servant-less middle class, Usonian houses heavily influenced suburban design in the postwar era.

Richard Neutra Born in Vienna, architect Richard Neutra (1892–1970) moved to the U.S. in 1923 and worked briefly with Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago. He partnered with Rudolf Schindler in California, at first as a landscape architect. Neutra developed his own practice and designed buildings in International Style as well as a geometric, West Coast variant of Mid-century Modern residential style. Neutra paid close attention to individual clients; his domestic architecture has been called “a blend of art, landscape, and practical comfort.” House plans are open and flexible as to function. By the 1950s, Neutra was designing commercial and institutional buildings.

Cliff May California designer Cliff May (1909–1989) is credited with the first modern Ranch, built in San Diego in 1932. This marked a deliberate new style of residential architecture—May’s designs are not the tract houses of a generation later. Consciously interpreting the ranchos of the mid-19th century, May was one of many notable post-Arts & Crafts architectural designers. A prolific promoter, May sold the style that he himself called “the early California ranch house” throughout the West. Working with landscape architects, May designed low houses that followed the contours of the land, enclosing a courtyard or patio with carefully planned views of nature. Floor plans were open, always with a family room. By the mid-‘30s, his Ranch houses had been published by Sunset magazine and nationally. The early Ranch maintained integrity even as the idea spread to other cities and suburban lots.

Traits the Ranch shares with Contemporary-style MCM houses include a low roof and deep eaves, anonymity to the street with more glass on the rear façade, and the inclusion of courts, patios, or atriums.

The rear façade of Eichler homes is often almost entirely glazed, making the interior seamless with the private backyard. Patios further extend living space.

Courtesy Zillow.com

Joseph Eichler A developer who left a legacy of integrity, Eichler (1900–1974) was a pioneer. Though his building career began at age 45—significantly, after he and his family rented a house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright—he nevertheless left 11,000 residences in progressive suburbs. Eichler hired architects to design reasonably priced homes that were modern, not traditional. In its day Eichler’s modernist style was embraced more warmly by the architectural press than by average homebuyers. Catherine Munson, Eichler Homes’ first female salesperson in the late 1950s, is quoted as saying that the typical buyer was wary: many house shoppers, she said, “hated our designs.” Although they found avid devotees in the Bay Area, the designs were indisputably different and ahead of their time.

Robert Rummer Oregon real-estate developer Rummer (born 1927) built about 750 Mid-century Modern residences in the Portland area ca. 1959–1975. His architectural vision, he has said, was “houses that bring the inside out or the outside in,” and indeed they feature expanses of glass, vaulted ceilings, and, often, atriums. Rummer credits Joseph Eichler and his architects, especially Jones & Emmons: Rummer read about Eichler houses in Look, House and Garden, Sunset, and Arts &

Architecture magazines. He met with Jones, who explained to Rummer how a modern, post-and-beam grid allowed the standardized use of large panes of glass. Many “Rummers”—now enjoying a cult following—closely resemble Eichler models. After 1975, Rummer turned to more Colonial-style and neo-Victorian designs.

Recommended Reading

• William Krisel’s Palm Springs: The Language of Modernism by Heidi Creighton & Chris Menard (Gibbs Smith 2016) The first major publication on the work of Krisel, a Southern California architect who also designed MCM houses for the middle class.

• Cliff May and the Modern Ranch House by Daniel P. Gregory (Rizzoli 2008) The designer’s houses from the Depression years through the 1960s.

• Atomic Ranch by Michelle Gringeri–Brown (Gibbs Smith 2006) A beautifully photographed book covering the postwar ranch, 1946 to 1970, with an emphasis on Modern design. IncludesEichler homes and those in Palm Springs, but also brick ranches and split-levels around the country.

• The Ranch House by Alan Hess (Harry N. Abrams 2004) Offering a broad but defensible definition of the Ranch in all its forms, the book draws parallels with Bungalow and Modern architecture. The bulk of the book is a 140-page chapter showing 26 restored homes (built 1935–1968).

• Eichler: Modernism Rebuilds the American Dream by Paul Adamson (Gibbs Smith 2003)

With period photos by Ernie Braun and Julius Shulman, this one captures the essence of Eichler, the builder who reshaped middle-class houses with his combination of architectural panache and social conscience. History, architecture, photos old and new.

• Furniture & Interiors of the 1940s by Anne Bony (Flammarion 2003) The modern, if contradictory, transitional interiors of the immediate postwar period.

• Western Ranch Houses by Cliff May by Cliff May and Paul C. Johnson (Hennessey & Ingalls 1999) Reissue of the 1958 volume, includes later modernist designs by May.

• Sunset Western Ranch Houses by Sunset Books edited by Cliff May (Hennessey & Ingalls, 1997) Re-issue of the first edition of 1946, the beginning of the genre.

• Eichler Homes, Design for Living by Jerry Ditto (Chronicle Books 1995) The first book on Eichler, documenting the breadth of his influence.

• EichlerNetwork.com

• EichlerSoCal.com

• MCMDaily.com/joseph-eichler

• MidCenturyHome.com