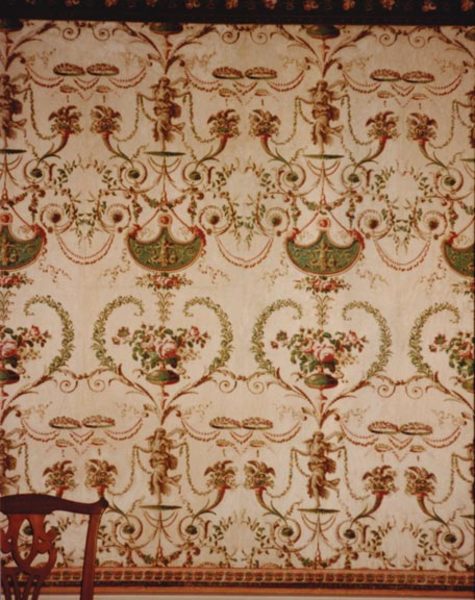

Dominant motifs that created repeating diamond shapes when viewed from a distance was another way in which wallpaper could present diaper patterns, as seen on this example from the late-18th-century Phelps-Hatheway house in Suffield, Connecticut. (Photo: Robert M. Kelley)

The trellis is arguably the most important building block of wallpaper design. How basic is it? Consider that traffic patterns in downtown Boston follow what were once cow paths, while those in Chicago evolved from a grid. Trellis wallpaper unites both types of traffic patterns to feature plants and flowers wandering over a stationary, symmetrical base. The end result combines action and repose, the yin-yang of Western wallpaper decoration.

Wallpaper history is full of trellises and their related forms: diamonds, grids, diapers, and squares, all of which continue to frequent wallpaper designs, with several manufacturers offering reproductions of vintage patterns from the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries. Before choosing from the many reproduction prints available, however, it helps to know how wallpaper patterns evolved over time.

Diamonds in the Rough

Until 1650, patterned paper was predominantly used to line boxes and trunks, and most designs were rather boxy as a result. Even elaborate designs were restricted by the sheet size, which was rarely larger than 22 x 22. In the years leading up to 1700 or so, however, fresh designs were encouraged by a new technique: joining the sheets end over end at the factory to create one long strip. The joined sheet encouraged innovation. Because more space was available, designers could arrange motifs within the sheet in new ways, often creating diamond shapes in the process. These motifs were usually split at the paper’s edge and joined side by side on successive sheets, resulting in the straight match. Another development was the drop match, in which alternating sheets were dropped half the distance of the design. This placement created a virtual diamond that resulted from the paperhanging technique, not from the motif itself. Any design, when viewed from a distance, would take on the diamond shape, which was more interesting than a square yet just as symmetrical.

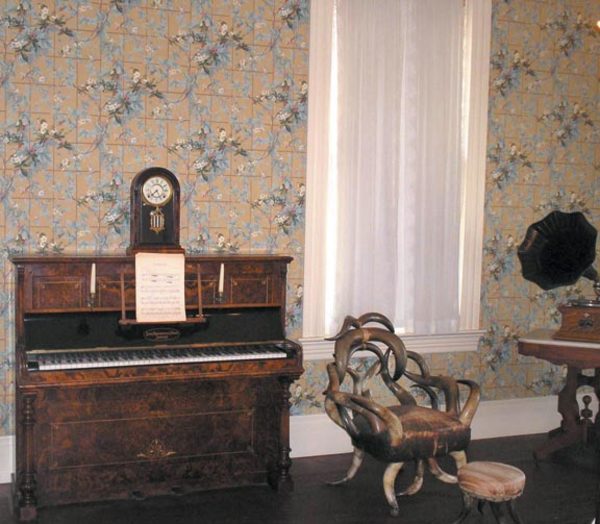

The lattices for trellis paper are diamonds or squares, such as this pattern in a room at the Kearney Mansion in Fresno, California. (Photo: Courtesy of the Fresno Historical Society)

The drop match was an important new tool, especially for large, formal patterns. Flocks (patterns that imitated woven fabrics) and arabesques (elegant, neo-classical designs) shared the same problem-they could look deadly dull when hung straight across. The drop match solved this problem by introducing variety.

American paperstainers regularly copied foreign wallpaper patterns using the same manufacturing technique of carving designs into wood blocks, dipping them in ink, and stamping the paper with the blocks. However, they soon found that depicting natural forms, especially the human face, required a higher degree of block-carving skill than was readily available. Instead, domestic producers concentrated on the backgrounds and brought out a variety of vibrant mosaic designs in all sizes between 1810 and 1840. These home-grown designs filled the demand for cheap, colorful backgrounds. Many of them can still be seen appearing behind dour-faced sitters in the folk art paintings of Jacob Maentel and Henry Walton.

In the process, the simple diamond form became much more than a framework because it began to sprout leaves, curlicues, pinstripes, shading, and shadow lines. All this decoration had the effect of making the background more prominent.

The parlor at Wisconsin’s Villa Louis bears lincrusta, a paintable embossed wallcovering, in a design whose dots form a diaper pattern. (Photos: Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

Grids of a Fashion

Diapers, which decorate materials from masonry to textiles, are a pattern of repeated motifs that were often used on dadoes and occasionally along borders, where they finished the edges nicely. The patterns were originally small-mere texture or embellishments on a grid. When diapers were used as the backdrop in wallpaper, dots or other small designs often peppered the intersections. Part of the success of the stately early 18th-century flock patterns was due to the rich embellishment provided by these diaper backgrounds.

Later, larger diaper patterns of medieval, Elizabethan, or Gothic forms found their way into wallpaper. But whether large or small, diapers remained static, whereas a trellis pattern conveyed movement and growth. Like the iron grid used on prison doors and windows, the diaper forms could appear oppressive, and though they tended to lack the dynamism of the floral and leafy motifs seen in trellis paper, they have an abstract appeal. Many 19th-century tastemakers praised the simple decorative quality of diaper forms because when they were used, the papered wall remained a flat, two-dimensional surface. An influential designer who showed how to carry out this idea was Christopher Dresser, who championed art botany-a stylized artificial art form with botany as its basis-in the 1860s and 1870s. He advocated supplementing floral motifs with sophisticated tints and diaper backgrounds for a more artistic approach.

Ode to a Trellis

For those who admired illusionistic, three-dimensional effects, there was the trellis, a grid that looked like a lattice. Evoking images of arbors with their trailing vines and flowers, the classic trellis pattern aimed to bring the outdoors in, provided that certain rules applied. For instance, House and House Furnishings, a British decorating book published in 1841, advised against using any pattern with lines crossed so as to form squares for a low-ceiling room, but took a different view if the lines were sloping or diagonal: A diamond trellis pattern, with a slender plant creeping over it, looks well in a small summer parlour. When a diagonal design had no plants or flowers, the trellis grid was often elaborated to resemble a lattice.

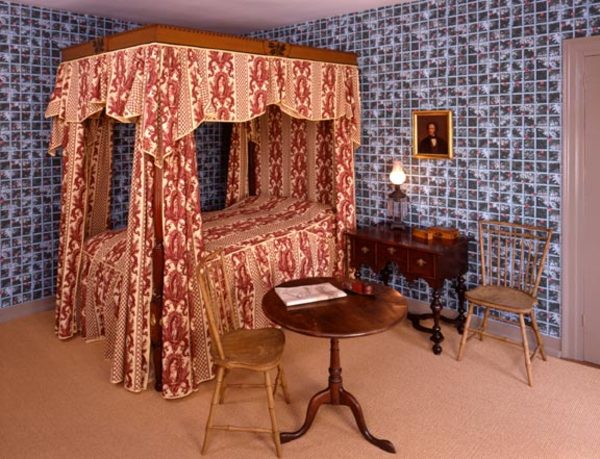

There’s no missing the grid on this French trellis wallpaper in a bedroom at the Wadsworth-Longfellow House in Portland, Maine, the boyhood home of the celebrated 19th-century poet. The paper is a reproduction based on the room’s 1826 decor. (Photo: David Bohl/Maine Historical Society)

You didn’t have to be a Romantic poet to notice that grids and flowers were a perfect combination, but several did. Thomas Jefferson Hogg, a friend of Percy Shelley and his first biographer, described what happened when the pair went apartment hunting in London and in one of the flats discovered trellis wallpaper, something that was relatively uncommon at the time. There were trellises, vine leaves, with their tendrils and huge clusters of grapes, green and purple, Hogg wrote, explaining that Shelley found it all delightful. He went close up to the wall and touched it. Then, Shelley told Hogg, We must stay here; stay for ever.

So strong was the attraction for paper roses among Romantic poets that James Leigh Hunt insisted on decorating with them, even though at the time he was serving a two-year prison sentence for calling the Prince Regent a fat Adonis. Nevertheless, Hunt was able to bribe or charm his jailers into letting him occupy and decorate several rooms in the prison’s infirmary. I papered the walls with a trellis of roses, Hunt wrote. I had the ceiling coloured with clouds and sky; the barred windows I screened with Venetian blinds. Charles Lamb declared that there was no other such room, except in a fairy tale.

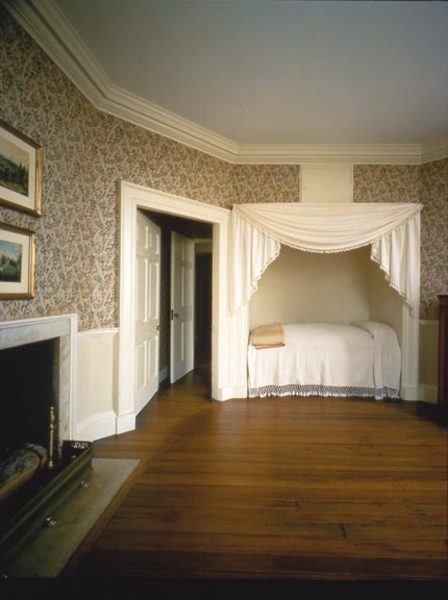

Called “Fox Grape,” the pattern of this trellis wallpaper dates to at least 1790, when Thomas Jefferson purchased it for a guest room at Monticello. (Photos: Monticello/Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc.)

Trellises may have been somewhat rare in England in the early 19th century, but by mid-century that had changed. In a 1988 article for Country Life magazine, British author Pauline Flick reported that many of the wallpaper registrations between 1842 and 1883 were of diamond designs, ranging from the neat diaper patterns recommended by Owen Jones to ivy plants climbing up a crisscross framework of wooden poles. Naturally, mid-century designers came up with fresh variations for their favorite theme. The designers, Flick wrote, produced trellises smothered with jasmine and honeysuckle, bunches of rosebuds tied with intersecting ribbons, formal quatrefoil motifs like the diamond panes of a stained-glass window, and countless others.

As usual in the wallpaper world, a good idea wasn’t considered perfected until it had been run into the ground. Manufacturers flooded the market with multi-colored floral patterns, most of them based on diamond modules. During the design wars that filled the latter half of the century, critics often scorned the homely, predictable, floral trellis and its related forms. In Household Art, an 1893 book edited by Candace Wheeler, one theorist complained about the dreariness of an English bedroom with its 40-or 50-year-old wallpaper on which great, staring bunches of ill-shaped flowers are daubed of every conceivable hue. The author was further dismayed that these same wallpapers could be purchased in any American town, appearing all too often in the bedrooms and sitting rooms of middle-class families. The United States, according to this author, may have achieved design parity with England, but it was only for bad design.

Trellises continued to decorate the walls in both countries as either bold frameworks or more subtle William Morris prints, most of which achieved the ideal of appearing trellis-like without actually showing the trellis. One exception was the first wallpaper Morris designed, that of an unusual square trellis. Morris created Trellis in 1862, a pattern that was inspired by his garden at Red House, which was organized on a medieval plan with square flowerbeds enclosed by rose-covered wattle trellises. The pattern combined the simplicity of floral elements taken from medieval woodcuts, carefully rendered birds (drawn by his architect friend Phillip Webb), and a unique, undulating perspective. Flowers and vines were featured in both background and foreground, intertwining with the trellis.

The pattern remained a personal favorite for Morris, and he chose it for his bedroom at Kelmscott House, his London home for the last 18 years of his life. It must have satisfied his criteria for wallpaper design, which he believed should mask the construction of pattern enough to prevent people from counting the repeats while managing to lull their curiosity to trace it out.

Robert M. Kelly is the principal at WRN Associates in Lee, Massachusetts.