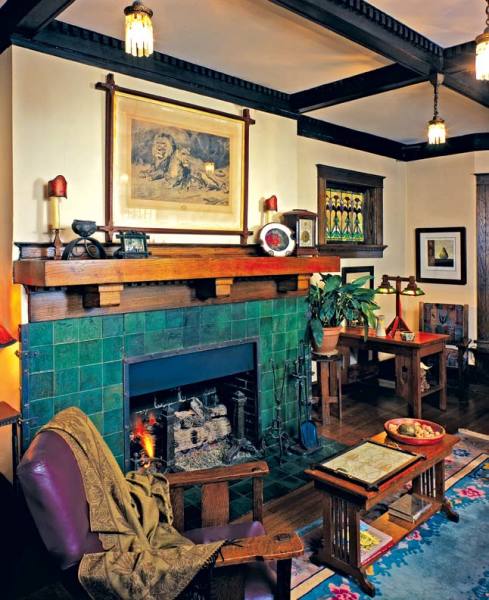

Stunning green tile accented by riveted iron straps makes the fireplace the centerpiece of the room in this Memphis bungalow. It’s hard to believe a previous owner had painted the entire thing red. (Photo: Linda Svendsen)

Fire fulfills a deep and primal role in the human psyche. Even today, when fires are no longer needed for heating or cooking, fireplaces are routinely installed in houses. In Arts & Crafts homes, the fireplace took on almost religious significance, and even bungalows in warm climates were built with one. Gustav Stickley was a big proponent, writing in The Craftsman, “The big hospitable fireplace is almost a necessity, for the hearthstone is always the center of true home life.”

Almost always a feature of the living room, fireplaces also were found in dining rooms, bedrooms, dens, and basements. Frequently the fireplace was surrounded by built-in benches or settles to form an inglenook, which often had a lowered ceiling that provided a feeling of coziness and set it off from the rest of the room. With or without an inglenook, the fireplace usually was surrounded by some sort of built-ins—often glass-door bookcases with high windows above, but a drop-front desk on one side was fairly common as well.

Bricks and More

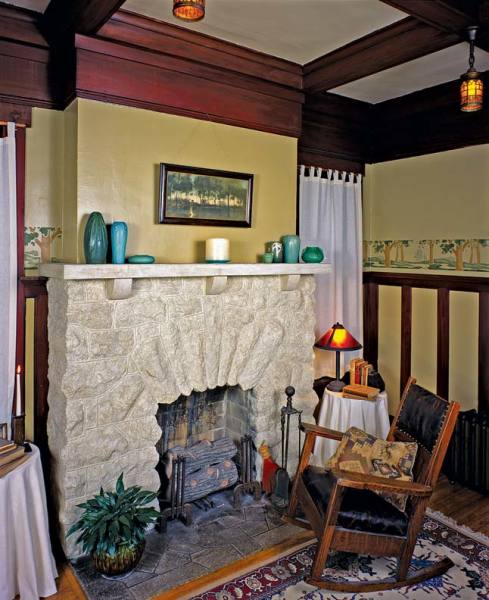

An arched limestone fireplace in another Memphis bungalow features a hearth of Rookwood tiles. The firebox is home to a set of 1930s vintage gas logs. (Photo: Linda Svendsen)

Chimneys were of masonry construction (brick, stone, concrete block), but the fireplace itself could be faced with a wide array of materials, including brick, stone, ceramic tile, cast stone, concrete, stucco, metal, or plaster—anything that wouldn’t burn. Brick was much favored, especially clinker bricks, those that had become vitrified and misshapen by sitting too close to the fire in the brick kiln. Before the bungalow era, clinker bricks were thrown away, making them cheap or even free, which no doubt made the eyes of many a speculative bungalow builder light up. Because clinkers were organic and interesting to look at, the movement embraced them, and soon they became trendy. Many other kinds of brick were used as well, from basic red or gold bricks, to wire-cut (textured) bricks, to bricks that were multicolored or spotted, and even decorative molded bricks.

Brick sizes have been standardized for centuries at 2¼” x 3¾” x 8″. They come in many colors and textures, and there are many ways of laying them, called bonds. Most people are familiar with running bond, where joints in each row are staggered by half a brick. Flemish bond features one brick turned on end every other brick. Multicolored brick patterns were referred to as tapestry brick. Brick also could be laid unevenly and randomly, known as eccentric brickwork. In Craftsman houses, brickwork was sometimes combined with river rocks to form what is generally referred to as peanut brittle, because of its lumpy appearance. Occasionally some use was made of glazed bricks, which were finished like pottery.

Set off by a spindled colonnade, this brick fireplace is surrounded by a generously sized inglenook with cushioned benches. (Photo: Douglas Keister)

Stone, including fieldstone, river rock, cobblestone, or rubble stone, had the rustic look esteemed by bungalow designers. Split-face ashlar (rectangular cut stone with an irregular face), though a bit more formal, also was used on fireplaces. Cast stone, a molded product made from concrete and fine aggregates, often was used in place of actual stone. It could resemble whatever sort of stone was required, although sandstone and limestone were most prevalent. Pressed concrete was another option, molded into panels about 1½” thick, and large enough to constitute the entire front of the fireplace. These were molded and colored to resemble tile or stone, and sometimes real tiles were inset as accents.

Green Motawi field tiles are combined with landscape and other decorative tiles in a seemingly random layout on this fireplace.

Ceramic tile was also much in favor as a fireplace facing, from plain 6″ x 6″ field tiles to decorative art tiles from now-famous Arts & Crafts potteries like Grueby, Rookwood, and Batchelder. Many fireplaces combined decorative accent tiles and field tiles, with accents set into the center above the firebox, in the corners, or down the sides. Landscape tiles were particularly favored, with scenes of medieval castles, Spanish missions, and English villages. Most companies also could supply matching ceramic corbels (to hold up the mantel), keystones (for arched fireboxes), and various trim tiles. It was possible to order the whole fireplace front from the same company so the firebox could be constructed to fit the tiles instead of the other way around.

Some Arts & Crafts houses had transitional fireplace facings—a Victorian/Edwardian holdover, featuring highly glazed majolica tiles, usually a smaller version of subway tiles, generally measuring 1½” x 6″ or 1¼” x 6″, but sometimes as small as 1″ x 3″. These had semitranslucent glazes with color variations from light to dark within individual tiles.

Some fireplaces were simply faced with plaster or stucco, although plaster also was combined with brick, stone, or tile accents. Some fireplaces may have been influenced by Spanish Revival styles—particularly after the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, designed in a Spanish Colonial style by architect Bertram Goodhue. A Spanish-influenced fireplace usually features a monolithic plastered firebox and chimney, often with built-in niches.

Many fireplaces were available in kit form: A builder could simply order a fireplace, and it would arrive with the masonry, the facing, and the damper, and could be turned over to the mason to install.

Finding the Fireplace

Clinker bricks are mixed with other bricks in a style of masonry known as “eccentric brickwork,” which becomes less eccentric as it moves up into the chimney. Just above the firebox, bricks form the letter A, the initial of the first owners. (Photo: Linda Svendsen)

Later owners, in some misguided attempt to “modernize,” may have painted, covered up, or removed the original fireplace facing. Painting seems to be the most common indiscretion—the most cringe-worthy update I’ve encountered is painting the bricks bright red, and the mortar bright white. The paint chosen to paint a fireplace is invariably glossy, and 99 percent of the time, it’s white.

After paint, the most popular refacing material seems to be the dreaded “used brick”—not really used, but rather tumbled after manufacture, and consisting of mixed colors, mostly red, but with a lot of white and black on the surface. “Used brick” also comes in a thin veneer version.

More recent “modernizations” may find the fireplace being refaced with 12″ x 12″ stone tiles. Granite and marble seem to be the most popular, but slate is up-and-coming—because it looks kind of rustic, people think it is therefore appropriate for a Craftsman home. It’s not. However, all of these “updates” can be removed, and fireplaces restored to their original luster, with a little time and elbow grease.

Built during a time of radiators, furnaces, cookstoves, and electricity, most Arts & Crafts fireplaces weren’t necessary for lighting, cooking, or heat, yet they were still thought to play a central role in family life, embodied in the phrase “hearth and home.” Art & Crafts designers knew that there is no substitute for the joy of gathering around the fire.

How to Restore an Arts & Crafts Fireplace

Remember that you can always restore a fireplace that isn’t as original as it should be.

With multiple layers of paint, a clinker-brick fireplace in a 1905 house was too far gone to save, so designer Michelle Nelson created a new covering that incorporates handmade tile and a custom-made redwood mantel.

- If the fireplace facing has been painted, that’s easy to remove from tile; it’s harder to get off brick or stone, but still doable. (It will involve chemicals, scrubbing, and probably dental tools.)

- If the original fireplace was ripped out and replaced with something really horrid like a 1970s woodstove, remove it and build a proper fireplace that complies with current codes. If the facing has been covered up, you’ll need to rip off the covering. Sometimes you’ll find great tiles beneath; sometimes you’ll find nothing because previous owners removed the original facing. At that point, you’ll have to figure out what to reface it with.

- If you can’t deal with stripping paint, there is always the option of repainting in a more brick-like, stone-like, or tile-like color. (Don’t use semi-gloss paint—bricks and stone aren’t shiny, nor is most Arts & Crafts fireplace tile). Or you could faux paint it to look like brick or stone, although if you’ve never faux painted before, you should practice (a lot) before attempting the fireplace. (It might be worthwhile to hire a decorative painter.) Never paint an original, unpainted fireplace for any reason.

- If the fireplace has already been rebuilt or refaced with something inappropriate, it may be possible to simply cover it up. Many brick manufacturers make thin versions of brick for use as veneer (unfortunately no clinker brick), and tile is another option. Most tiles in the bungalow era were glazed by hand, even if the tiles were machine-made, which results in less uniformity in the glaze than modern tiles. Because a fireplace surround is U-shaped, tiling a fireplace is less straightforward than tiling a countertop (an arched firebox complicates things further). Tiles bigger than 6″ x 6″ tend to read as modern. Watch your spacing; fireplace tiles tended to have wider grout joints than the minimal ones used in vintage kitchens and bathrooms, especially if the tile was handmade. Joints up to 1⁄2″ were common, although narrower joints (usually not less than 1⁄8″) also were used.

Jane Powell is a restoration consultant and the author of five bungalow books.

Online Exclusive: Check out our list of inspiring Arts & Crafts fireplaces to visit.