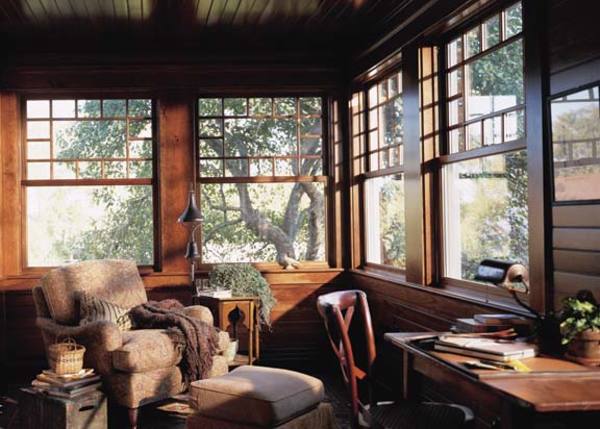

Queen Anne windows were popular from the 1880s into the 1900s and are now made by several window manufacturers. (Photo: Andersen Windows)

For centuries, writers have compared the windows on a house to the eyes of a person, and rightfully so. Windows are much more than functional ports for admitting light and air into a building; they are important architectural elements that in many instances showcase the new ideas and creative thinking popular at the time.

Take the turn of the 20th century as an example, an era when new directions in housing—as exemplified by bungalows, Foursquares, and Prairie-style homes—were coming into vogue. A close look at the ways in which these new breeds of windows differed from those in the previous century can aid owners of post-Victorian houses who plan to restore or add on to an existing building. As luck would have it, now more than ever, a host of modern window manufacturers are creating historically accurate products or, at the very least, new interpretations of originals that are a good fit for these houses.

Creative Casements

The dramatic popularity of casements is one example of how windows changed at the turn of the 20th century. Because casement windows were hinged on one side like a door, they opened more fully to offer better ventilation and an unhindered view of the outdoors. Perhaps that helped fuel their popularity within the Arts & Crafts movement, which touted bringing the outdoors in as a major theme.

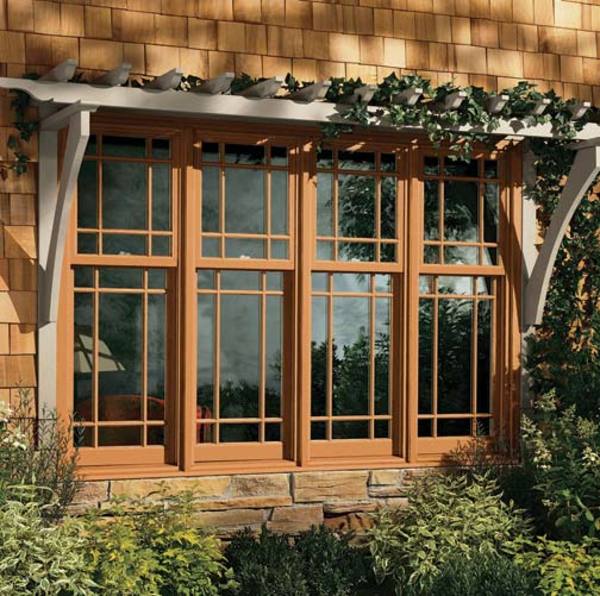

Modern manufacturers have begun offering windows with classic, turn-of-the-20th-century muntin patterns, including these Prairie-styled sashes. (Photo: Marvin Windows)

Casements were also viewed as a fresh step away from sash windows. Stephen Calloway writes in Elements of Style, “In the early years of the Arts and Crafts movement sash windows were associated with iniquitous, modern plate glass.” Of course, in addition to being a modern, less formal window treatment, casements afforded some nice decorative options, too. Because they presented a continuous stretch of glass unbroken by sash, they could display muntin patterns designed to produce a bigger impact.

In fact, muntins appeared in a variety of shapes on early 20th-century casements and were used with great creativity to add to a building’s overall warmth and charm. In a 1902 issue of The Craftsman, Irene Sargent writes, “The English home-feeling can be inspired by muntined windows with quaint shutters.” That may be why so many bungalows feature vernacular, decorated wooden casements. Typical lights could include diamond shapes, which tweaked designs that originated on medieval buildings, and lozenge shapes—elongated rectangles ending in a point—which were new and unique at the time.

Designers of the day offered a rationale for the new trend in window design, with none more influential than Gustav Stickley. In his 1909 book, Craftsman Homes, he writes, “Another feature of typical Craftsman construction is well illustrated in the windows used in this house. It will be noted that they are double-hung in places where they are exposed to the weather and that casements are used when it is possible to hood them or place them where they will be sheltered by the roof of the porch.” The accompanying illustration shows a house with a combination of 9/1 sash windows and casements divided into 15 lights. Even Stickley’s own house in Parsippany, New Jersey, was built with diamond-patterned casements.

Much has been written about the Prairie school’s preference for horizontal lines, a design idea that clearly extended to windows. While individual windows were usually tall casements, they tended to be grouped together in long banks, or ribbons, that dramatized the building’s horizontal nature. If you think of the Prairie style, the venerable Frank Lloyd Wright probably comes to mind. Wright helped pioneer new uses and placements for casement windows. Karen Sweeney, the restoration architect for the Frank Lloyd Wright Preservation Trust, says, “Ribbon window placement was an important part of Prairie-style architecture that tried to create buildings with horizontal lines. There’s no doubt that Wright’s use of ribbon windows inspired other people to use them, too. “These window banks also allowed for a wide-ranging outdoor view from an inside vantage point, especially when they continued around the corner of a building. “Wright used ribbon windows to break open the box and open up rooms so they seem bigger,” says Sweeney. “Wrapping windows around a corner helped.”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s designs appear on new sash, casements, and fixed-frame wood windows. (Photo: Andersen Windows)

Of course, ribbons of casements afforded plenty of decorative opportunities, and new muntin patterns appeared here as well. One of the best known is a pattern of simple lines that places squares in each corner of the window. While no one can say for sure where this pattern came from, perhaps the inspiration lies in the ubiquitous Queen Anne sash that predated it—which boasted a large, clear pane ringed by a border of squares. If you clean Queen Anne sashes up a bit by removing the middle squares, they form a pattern that closely resembles this nine-light Prairie window.

Despite their horizontal groupings, most Prairie-style casements were defined by vertical details, either a series of narrow lights or, in more high-style examples, the incorporation of intricate leaded designs. Wright took these designs to their zenith. As stained-glass expert and author Julie Sloan explains, “He called his windows ‘light screens,’ a term that evoked Japanese shoji screens, which were arranged in bands as his windows were. In Wright’s buildings, inside and outside were joined by these large expanses of glass. The intricately patterned lines of lead maintained the boundary of the building’s structure and sometimes echoed its silhouette, but the sparkling glass made the openings permeable, almost diaphanous.”

A New Style of Sash

By the 1890s, just when technology made large, single-light sash windows affordable for everyone, designers and homeowners alike became increasingly enamored with decorative patterns, particularly for the top of the window. “Plain windows with small lights above and a single, large light below are always practical,” pronounced architect Charles B. White in 1914. “The upper sash can be divided into six or eight equal lights, with small lights at the side and larger lights in the center.” A similar trend is noted in Calloway’s Elements of Style: “A popular arrangement was to pair an upper sash bearing small rectangular lights with a single paned lower sash.”

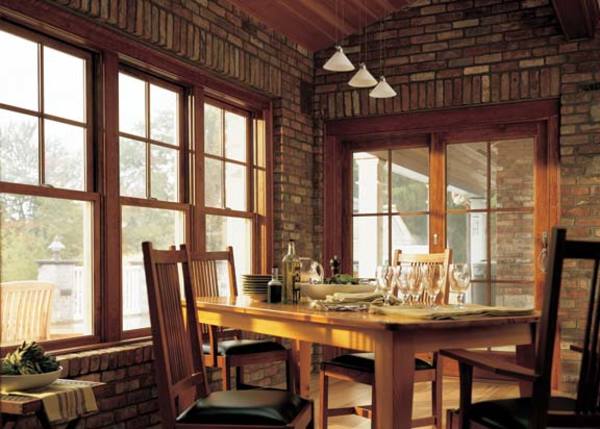

With top-heavy windows, muntins didn’t have to be elaborate, as the simple 4/1 pattern of these modern windows shows. (Photo: Andersen Windows)

Such windows differed substantially from those based on Georgian models for popular Colonial Revival houses. Instead, these new picturesque windows were ahistorical (as well as horizontally asymmetrical) patterns created for a new effect. Along with stock design, art glass windows, they were the stuff of mass-market, post-Victorian bungalows, Foursquares, and Prairie-style houses. Manufacturers’ catalogs grouped the scores of inventive patterns under some basic headings. Double-hung windows with equal-sized sash were variously called “divided top,” “fancy top,” or “cut top” windows. When the meeting rail was proportioned above center in a double-hung window or the same appearance was built into a single sash, the result was a cottage front window or sash.

Roberts Illustrated Millwork Catalogue, a compendium of products from Chicago’s E.L. Roberts & Co. at the turn of the century, shows a variety of sash windows with decorated upper panes. There are windows patterned with large harlequins and those bearing 36 small, square lights, as well as windows with a large diamond shape flanked by trapezoids, and others with a circle in the middle surrounded by various squares and rectangles. Homeowners of the day had a lot of leeway for choosing windows, and these selections were just the standard offerings; special orders could be had for a premium, too, which just goes to show that at the turn of the 20th century, options were everything.