Judging by the open shades, the small, inexpensive three-branch chandelier in the 1849 Farnsworth Homestead is probably from the 1880s.

Genesis got it right. The victory of light is the key to human existence. However, not until the late Victorian decades did kerosene lighting end the tyranny of night for nearly everyone in the United States. Gas lighting was the posh, pretty-boy, poster child of Victorian interior lighting, but its technology and expense restricted its use to wealthy urban homes and public places. Likewise for electric lighting, which began in 1879 when Thomas Edison perfected the commercial incandescent lamp and, more important, a system to power it. Here’s a glance at how, just more than a century ago, these three sources brought new levels of light into houses for the first time and the impact they had on fixtures, décor, and the people who used them.

Oil for the Lamps of Columbia

John D. Rockefeller is stigmatized as one of the bad boys of late Victorian capitalism, but his consolidation of petroleum refining made kerosene affordable for everyone. Delivered down the web of post-Civil War railroad tracks that united a largely rural country, there was also shipped a vast array of kerosene lighting devices from the fundamental to the fancy. There’s no need to get lost in lumens to appreciate how much light output improved, but a kerosene flame will provide about three times the brightness of a candle flame—with a candle flame being about equal in brightness to an overcast sky.

The two-light kerosene pendant fits the era of the 1870 Norlands House. Decorative glass chimneys were also sold for use in such public rooms and to complement the painted ceiling.

Kerosene lighting was superior to candle but not inherently safer. Remember how a kerosene lantern kicked by a cow started the Great Chicago Fire of 1871? There are numerous gruesome accounts of women burned to death while refueling kerosene lamps when the fuel ignited after it spilled on their billowing skirts. Explosions were common because unscrupulous suppliers adulterated kerosene with more volatile fuel that was less expensive. Few then would disagree with the Victorian domestic sages Harriet and Catherine Beecher. In their famous 1869 guide, American Woman’s Home, they pronounced, good kerosene oil gives a light which leaves little to be desired.

If you restore some Victorian verisimilitude to your house via working kerosene lighting, plan on making a safe place to clean, trim, and refuel your lamps away from where they are burned. The Beecher sisters suggested a lamp filler, with a spout, small at the end, and turned up to prevent oil from dripping. They recommend lighting the lamp with a strip of folded or rolled paper, of which a quantity should be kept on the mantelpiece.

A wood engraving from the title page of the 1860 Dietz & Company lighting catalog displays how diverse the market for kerosene lighting had become by the mid-19th century. From the small, utilitarian hand lamps at the outside, the models march up the social mountain to the very rich tripod lamp in the center. Printed paper lampshades on the pair next to the hand lamps are among the rarest ephemera of Victorian lighting. Dietz apparently supplied them ready-made and possibly patented them as such. Chromo-lithographed paper lampshades also were available as uncut flat sheets for home construction.

The 1858-1860 Morse-Libby House (also called Victoria Mansion) in Portland, Maine, is renowned for its lavish gas chandeliers—one of the few known examples in the Neorococo style. The large ball globes of this 12-arm extravaganza—designed to fit the Gustave Herter interior—have minute bases typical of the date.

If you like prism hula skirts on your late Victorian kerosene ceiling fixtures, there is an ample supply of old and new examples available in a variety of colored shades. If your budget is limited, come down from the ceiling and consider more modest kerosene lamps on mounted wall brackets. Lamp brackets and flowerpot brackets appear together in late Victorian hardware catalogs. From a distance, they look the same. Although you are more likely to find antique flowerpot brackets, don’t use them for kerosene lamps. A flowerpot knocked on the floor is a mess; a kerosene lamp is a disaster. A must for any functional kerosene ceiling lamp is a smoke bell to collect the soot and keep it off the ceiling.

Historical Gas

Gas lighting is dead. To my knowledge, the only place and time Victorian gas lighting comes to life is the Christmas Eve service at St. Timothy’s Episcopal Church, in Roxborough, Philadelphia. They say it’s quite a sight to see two people racing around the outer aisles, one opening the late Victorian gas jets that St. Tims never took out and another lighting them.

Gas chandeliers were often sited over tables. In some versions of this three-arm model, the central light could be lowered for reading.

My only experience with gas lighting took place more than 30 years ago during a Victorian Society in America annual meeting in Cincinnati, Ohio. As a special treat, we were taken over the river to Covington, Kentucky, for an evening at what turned out to be a Victorian time capsule. Our hosts removed dust covers from the original seating of a double parlor—containing not one but two suites of Belter furniture. But it was the gas jets on the wall that overwhelmed me. The hiss, the heat, the hot colors. At that moment I realized why and when the expression Let’s step outside for a breath of fresh air! entered the American idiom.

The technology of gas lighting is dead, but not its outward forms. In the social scale of Victorian lighting devices, gas lighting fixtures remain where they always were: at the top. A good example of an electrified reproduction gasolier is the five-arm fixture with open shades that imitates what originals looked like during the 1880s and ’90s. Compare this with the ball globes of the double-tiered, 12-branched gasolier—the kind popular from the 1850s through the 1870s in Italianate or Second Empire mansions. Why the shift? The new style globes of the 1880s were made wider at the base as well as across the top to increase air flow and reduce flickering.

For the majority of lighting’s history, any artificial light source has never been sufficiently beautiful in its own right. It needed a base. It needed a container. It needed a shelter. It needed a reflective device to make the most visual contribution to the room, and gaslight was no different. Fixtures were based upon all of the prevailing decorative styles of the era from Neoclassical and Rococo, to Neo-Grec, Aesthetic, and Eastlake.

Electrified gasoliers also can be historic. The body of this Morse-Libby House chandelier is original to the building, but the improved-style shades were added when the fixture was electrified in 1902.

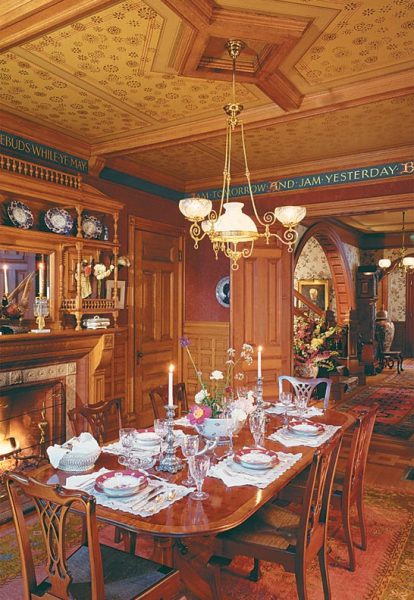

A good reproduction gasolier cannot convey gaslight-era ambiance on its own. In the best Victorian manner, the reproduction interior is a harmony of light, color, pattern, texture, and scale. A big help is the proper arrangement of dado, fill, frieze, ceiling, and centerpiece wallpapers. Their tertiary colors bask in the warm spectrum that emits from reproduction carbon filament incandescent bulbs. I’m especially glad to see the ceiling centerpiece. To the sensibility of a Victorian eye, plugging a chandelier in the modern manner into a bare ceiling looks bad because it was bad manners for anything or any person to meet another without a proper introduction. I also like the portiere drape and the proper use of the picture molding with a medallion and wrapped wires.

The Electric Circus

During the 1890s, as electric lighting gained in popularity, makers of gas lighting devices added electric lines and sockets to their gas jets. It’s easy to tell the difference between a gaslight fixture and an electric light fixture. With the exception of later Welsbach mantle incandescent lights, all forms of Victorian combustion lighting have shades that point up. Late Victorian incandescent lamps usually have shades that point down. An authentic late Victorian electric fixture is never at a near-horizontal angle. The reason is the large, fragile carbon filament of early lamps (commonly called bulbs) could break under the stress of gravity or vibration. (Welsbach mantle fixtures, which operate like gasoline camping lanterns, always point down and were popular from 1890 to about 1910.)

Though the Homeport Inn in Searsport, Maine, was built in 1861, this early all-electric “shower” fixture from the 1910s is now part of the historical décor. The anachronistic oil font in the center appears on many colonial-style models of the time and is actually Flemish-inspired.

If authenticity is your goal, it’s worth finishing your late Victorian electric lighting installation with authentic lamps. Though spending up to $16 each for reproduction carbon filament lamps seems expensive, they burn with a low, warm, amber glow that is the intended spectrum and intensity for the fixture and the room. The popular alternative to low-level lighting is putting modern lamps on a dimmer. This is not only inauthentic, but also it does not have quite the same visual effect. Inspired and educated eyes of Victorian interior designers, like their predecessors, learned by trial-and-error what colors looked best under available lighting conditions.

Late Victorian low-level lighting got a lot of its allure from associations with the interiors of 17th-century Dutch genre painting, revered at the time and throughout the Arts & Crafts period of the early 20th century. Released from dealing with heat and exhaust, fixtures were free to become artfully placed pools of light capped with stained-glass shades that scattered a jewel-like spectrum of colors towards delicious shadows. Perhaps more than the Victorian lighting that preceded it, the light fixture—especially its crowning glory—was a work of art. Nothing less could have been expected from a period called Art Nouveau or Arts & Crafts.

If anyone seriously wants to revisit late Victorian interiors, today’s bright and pervasive interior lighting must be banished. Be patient when you enter a late Victorian interior. Let your eyes dilate. It’s a wonderful experience to wait and see colors, patterns, and shapes emerge. Life among the shadows is relaxing. It’s comfortable. And its richly beautiful concern for proper lighting conditions is a small, but significant, part of what makes us devoted supporters of old houses.