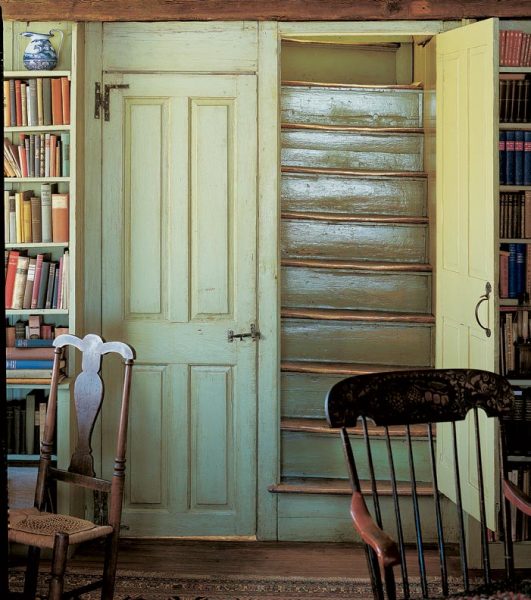

Simple thumb latches and an H-L hinge look just as authentic as the ancient stairs on this Colonial house.

Brian Vanden Brink

Before about 1840, the hardware common to most households was almost universally locally made. An 18th-century latch might literally be homemade; if not, it was probably the work of a local or itinerant blacksmith. Later, more advanced designs were cast in local foundries.

Perhaps that’s why the hasps, hinges, and latches of the colonial and Federal eras were so diverse. Some were so rudimentary that they would hardly be considered hardware to modern eyes: hand-carved wood knobs and pulls, for instance, or simple hook-and-eye latches crudely made with whatever metal came to hand. Other pieces, expertly forged by the once-common blacksmith, display extraordinary creativity and a degree of skill probably unequaled ever since, despite the present-day revival of hand forging and ironwork.

Brass hardware, so popular during the early 20th-century Colonial Revival, was extremely rare well into the 1800s, and was almost always imported. Even iron was used sparingly. Unlike today’s blacksmiths, who work with heavy metal stock that comes in uniform ½” widths, colonial blacksmiths used their considerable skills to make what little material they had go as far as possible. That’s why hardware that’s 200 years old is often remarkably light. Century-old reproduction hardware tends to be heavier, and because most of it was machine made, of uniform consistency.

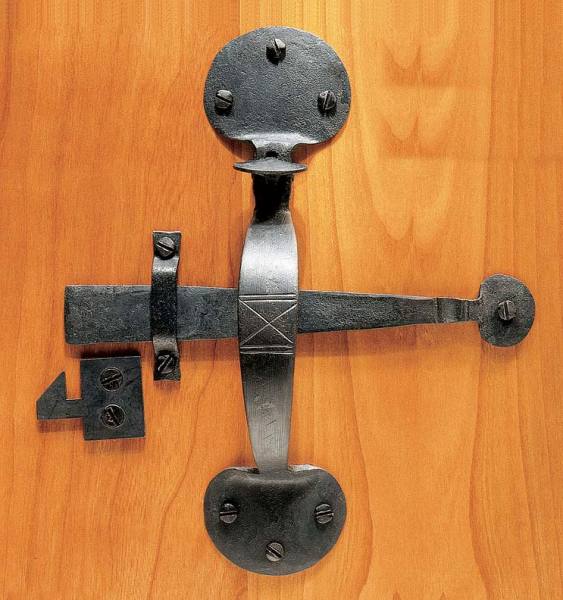

A Suffolk latch, closely modeled on 250-year-old originals, from Horton Brasses.

Before about 1800, the door latch was far more common than the high-style knob and mortise lock combination associated with fine Georgian homes. These latches were often ingenious, beautiful works of art. The earliest and crudest were made of wood—the kind that can still be found on old barns in rural New England or the mid-Atlantic.

Both wood and metal latches work the same way. A latch bar attaches at its hinged end to the door, with the free end extending beyond the face of the door to rest in a notched keeper (also called a catch or strike). The keeper is attached to the face of the door jamb. Opening the door is simply a matter of raising the latch bar.

The mechanism for raising and lowering the latch could be as simple as a string threaded through a hole in the door and tied to the latch (“keeping the latch string out” was a colonial expression of welcome and invitation), or it could be a wrought-iron latch. The earliest American-made iron latches are called Suffolk latches. On the outside of the door, the Suffolk latch has a curved grasp and thumb latch to work the latch bar on the interior. Blacksmiths came up with many clever designs and shapes for the cusp ends of the grasp; most common was the bean, followed by heart, spade, and diamond-shaped designs.

A pantry added to an 18th-century stone house in the 1920s features H-L hinges.

Jean Kallina

Other early latch designs include the spring latch, the Dutch elbow, and the Norfolk latch. Also called a plate latch, the lifting mechanism on a spring latch is attached to a metal plate that’s fastened to the door. Most plate latches have a small brass knob attached to a cam that works the latch bar when turned. In later versions, the plate was replaced with a flat, shallow box that contained the latching mechanism. The Dutch elbow, popular after about 1750 in areas settled by Germans, was also encased in a surface-mounted iron box. Instead of a brass knob or thumb latch, though, the lift mechanism was a graceful lever-like handle with an elbow bend.

While the Norfolk latch was operationally and mechanically similar to the Suffolk latch, there is one important difference: The Norfolk latch was machine-made in early foundries. The grasp was often made of cast iron, attached to a plate of rolled sheet metal. Popular between about 1800 and 1840, the Norfolk latch usually had a keeper that was mortised into the door, and the latch was easier to lift than that of the Suffolk latch.

A reproduction latch from Heritage Metalworks reflects high-style colonial worksmanship.

No door would function without a strong and functional hinge. Like the Suffolk latch, colonial hinges combined strength with beautifully wrought details. Some of the most authentic are the H hinge, the HL hinge, the rat-tail hinge, and the strap hinge. The last is an elongated design that ends in a cusp, like the Suffolk latch; cusp designs for strap hinges include such interesting shapes as a fleur-de-lis, crowned bean, acorn, tulip, and marigold.

Early locking mechanisms include rim and mortise locks turned with a bit key. Rim locks are mounted on the surface of the door; the more secure mortise lock is embedded in a pocket cut into the door. The advent of a cast-iron mortise lock in the 1830s set the stage for the doorknob to replace the thumb latch as the key operating mechanism for door hardware.

The earliest knobs, seen in the finest homes from the 1700s on, were brass. They were smaller than today’s knobs, and either round or oval (egg-shaped). Most of the ones made before 1840 were simple and unadorned. Porcelain (or “china”) knobs were imported in limited numbers during the 1700s as well; they became far more widespread in the 1840s, when American pottery companies began mass-producing them. Still widely found on homes built before 1850, many of these glazed knobs feature a pattern of hairline cracks, or crazing. The effect is not necessarily due to age: It often resulted from either an intentional technique or a happy accident in the final firing.