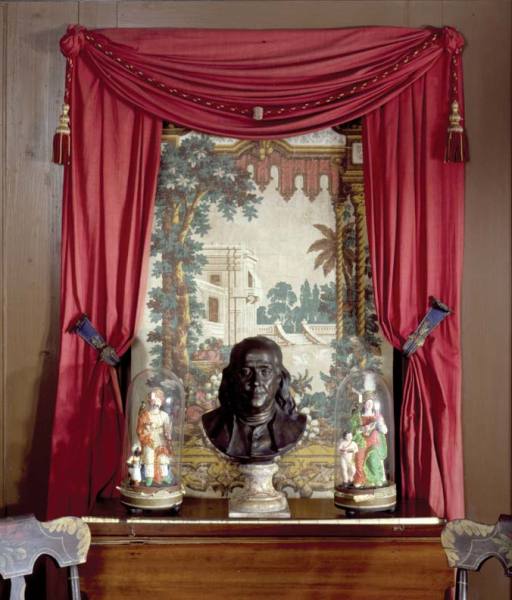

The flexible brass bands securing the curtains at Beauport Mansion in Gloucester, Massachusetts, were a mid-century alternative to tiebacks and pins. (Photo: Historic New England)

Whether tied back, pinned down, or strung up, the fabric adorning windows or stairs has always needed hardware to bully it into place. A simple rod gives the swags and tails of 19th-century drapery a spine, and it’s the rod again that browbeats carpet runners into submission so that they strike a path down the middle of a staircase. This interior-decorating version of tough love wasn’t always a simple matter of spare the rod and you’ll spoil the style, however, because it wasn’t exactly clear who was master in the relationship that hardware had with decorative taste.

In fact, hardware was a bit of a slave to fashion, evolving throughout history as taste and technology changed, and sometimes remaining in old houses, long after the styles it once supported had disappeared, to mystify future owners. The dazzling array of historically appropriate rods, bands, rings, finials, dust corners, and pins on the market today are downright confusing, if not outright mysterious, until you consider them in the context of how and when they were used. Then it all begins to make sense, so that never again will you ask, “Why is there a doorknob by my window?”

Early Victorian (1830-1850)

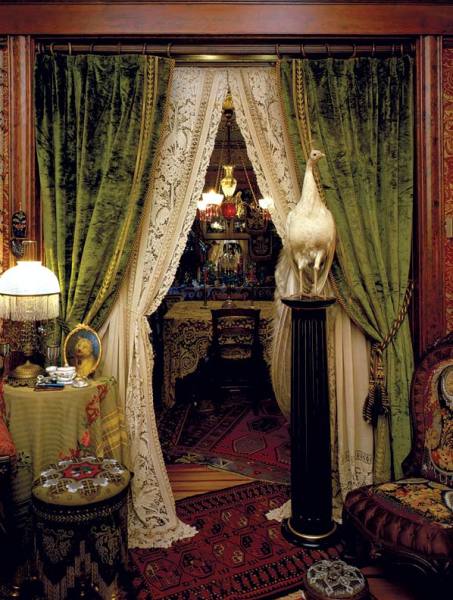

Portières, or doorway curtains, used the same rods and rings as window treatment. Popular from the 1870s until the end of the century, portières framed the entrances to public rooms, such as a parlor or dining room. (Photo: Linda Svendsen)

Until the 17th century, curtains were simple and functional, a panel or two of cloth hanging from a pole, their primary purpose to keep out drafts. Then the French invented drapery, which was a different idea altogether. Unlike curtains, which could be pushed aside to let in light, drapery didn’t move; it was arranged in artful, permanent swags, parallel to the floor and draped over a pole or suspended from a cornice. Sometimes, the swags had tails, but they, too, were purely decorative.

In the early Victorian era, French drapery came back in fashion, but because the hardware was secondary to the fabric it supported, poles and finials were rather plain. Often brass or wood, the poles measured an inch or two in diameter, ending in little cannonballs. Middle-class families, who had curtains rather than drapery, often used the same poles with brass or wooden rings for the curtains to slide freely. That style of rod and finial, whether for elaborate drapes or simple curtains, didn’t change much over the next 50 years.

Like curtain rods, stair rods were also plain; the pencil-slim iron cylinders were finished in brass and had simple fittings at either end to anchor them. “They didn’t call much attention to themselves because they had a practical purpose,” says John Burrows, founder of J.R. Burrows & Company, which supplies decorative furnishings for period homes. Long before non-slip pads were invented, stair rods held carpets in place. Once a year, the rods and fittings were removed, and the runner was shifted slightly up or down so that the nosing of the stair wouldn’t continue to wear out the same place in the carpet.

Stair rods, which first emerged in the late 18th century, were more elaborate in wealthy homes. Instead of plain cylinders, the ornate bars greeting visitors to the Edgewater Mansion in Barrytown, New York, are flat and fitted on each side with brackets that attach to the riser. (Photo: Paul Rocheleau)

There were exceptions to the cylindrical stair rod, usually in wealthier homes, which could afford more innovative designs. One style, for instance, was a triangular rod with simple stops at both ends, and another was a flat hollow bar that at each side slipped through a bracket, which attached to the riser. Fancier renditions placed metal scrollwork on top of the bar that stood out against the riser, although frugal homeowners often used the decorative rods only up to the landing to impress visitors. A plain rod secured the carpet for the steps that were out of view.

Mid-Victorian (1850-1870)

Window hardware, on the other hand, was shrouded in so much material by mid-century that it was completely hidden. Lambrequins, made of stiff fabric, framed the window’s top and upper sides, or another option was a valance, tucked under a boxlike cornice, covering only the top. Underneath the valance or lambrequin, floor-length curtains hung straight down and were gathered at each side, while a layer of lace undercurtains hung by the window.

The only visible hardware was the curtain pin (also called a holdback) that the heavier curtains fastened to when held open. Mounted to the wall or frame on each side of the window, curtain pins had an embossed brass head with a metal post that screwed into the wall. The curtain either tucked behind the pin’s head or fastened to it using a tieback, such as a strip of cloth, braided cord, or ribbon.

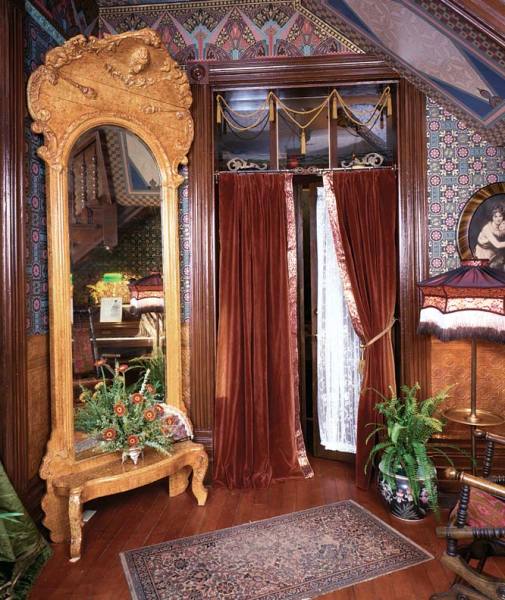

As window treatments simplified, finials became fancier. (Photo: Brian Vanden Brink)

With their medallion heads and thick stalks, the pins often looked like misplaced doorknobs, but by mid-century, the hardware for restraining curtains had broadened considerably. The brass heads appeared in different designs and shapes, such as a basket of flowers or a rosette, even Rococo scrollwork, says Walter Ritchie, a decorative arts consultant for historic houses and museums. Pressed glass was also used, often in the shape of a flower or shell. Curtain bands were yet another option. These flexible u-shaped pieces of stamped brass gathered the curtain inside the band, which at the back screwed to the wall. The bands were decorated in scrollwork, flowers, or leaves, their ornamentation sometimes matched by the gilt or brass cornices crowning the tops of drapery.

Late Victorian (1870-1900)

As window treatments grew more elaborate, 19th-century decorating maven Charles Eastlake was among the first to urge more restraint—not for the curtains, but for consumers, whose taste for multi-layered window treatments he deplored. In his 1868 book, Hints on Household Taste, Eastlake advocated an end to lambrequins and valances and a return to suspended curtains from exposed metal rods and little rings, hardware that in his view Victorian window treatments had “burlesqued.” Consumers, however, were not easily weaned off of the more elaborate styles, which persisted so that nearly 30 years later, Edith Wharton and Ogden Codman, writing in The Decoration of Houses, were still remarking derisively about “windows dressed up in ruffles.”

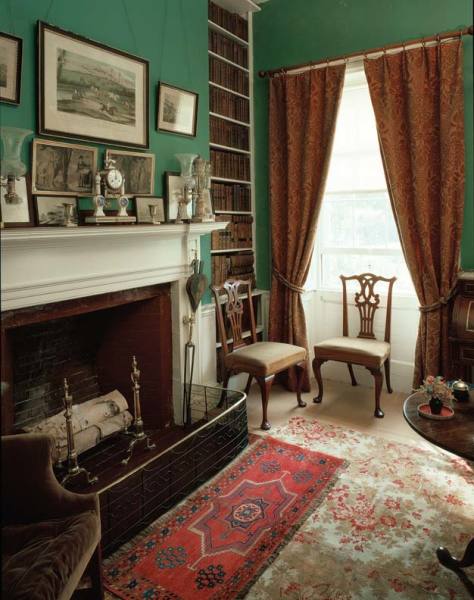

An anachronism in this Victorian house, crane rods weren’t invented until the 1920s. Designed for casement windows, crane rods swung open like a door to let in light. (Photo: Linda Svendsen)

Fashion followers who adopted Eastlake’s simple style retained the decorative pins and lavished their creative taste on the previously hidden hardware instead. Rods, for instance, became thicker and heavier even when they supported the same amount of fabric. Around this time, too, finials broke out of their cannonball rut and were shaped as acorns, urns, or gigantic flowers of brass, gilt, or bronze. The same hardware, minus the finials, suspended portières or doorway curtains, a fashion trend that began in the 1870s and lasted until the end of the century. Portières marked the entrances to public rooms, and like window curtains, they secured at the side with cords and curtain pins.

As for stair hardware, the once plain brass rod began to be “etched with all sorts of designs,” says Richard Nylander, senior curator for Historic New England. One 1880s stair rod, for instance, had a spiraling Greek key etched along the brass hollow tube to catch the light.

Even science affected stair hardware, with dust corners emerging in the 1880s, probably in response to the growing acceptance of germ theory, surmises Gail Caskey Winkler, co-author of Victorian Interior Decoration. Placed at the juncture of riser, tread, and stringer, these mostly brass and occasionally wood pieces were easier to dust. “The dust corner looks like an imploded triangle, but pressed into a corner, it creates a nice rounded surface,” says Steve Conant, president of Conant Custom Brass, which makes a dust corner based on an original 19th-century design.

Early 20th Century (1900-1930)

Although the diameter varied, a plain rod with cannonball finials never went out of style and often mingled brass rings with wood poles or vice versa.

Eastlake’s minimalist ideas for curtain hardware finally caught on at the turn of the century with the Arts & Crafts movement, which eschewed fat rods, fancy finials, and pins in favor of the modest little poles and rings that had been in fashion nearly 100 years earlier. The hardware was often wood, wrought iron, or copper, but perhaps the biggest change to hit window treatments was a 1907 invention from the Kirsch Company: a telescoping, u-shaped, flat rod that clipped onto brackets at the two short ends of the u. Instead of hanging from rings, the curtains were shirred onto the rod, which could lengthen or retract to fit different window widths.

The Jazz Age introduced crane rods for casement windows, a popular 1920s architectural feature. Fastened to the wall by a hinge on one side of the window, crane rods swung open and shut like a door. A single finial appeared at the end opposite the hinge, and decorative metalwork sometimes crowned the rod. The brass or copper poles often had elongated finials, shaped like a leaf or spear, rather than the more bulbous forms popular in the Victorian era.

Traditional rods, however, continued to use rounded finials, often in polychromed wood, the rods resting on large wood brackets painted in the same bright contrasting colors as the finials and pole. Art Deco designs added a third ornament in the center that rose above the rod like a rising sun on the horizon. By this time, consumers could choose hardware made from cast iron, brass, wood, copper, or steel. Even curtain pins returned for a time, bearing similar floral designs from 50 years before.

But stair hardware was quietly perishing. Wall-to-wall carpeting rendered stair rods obsolete, and dust corners disappeared once vacuum cleaners emerged. Even elaborate curtain rods began to peter out with the onset of the Great Depression, and as consumers searched for less expensive alternatives, one style in particular caught their eye: a slim wood or brass pole ending in two little cannonballs.