Victorians saw plants as symbols of moral values and emotions, and brought them into the home year-round for inspiration and solace as well as for inexpensive décor. (Illustrations: Marilyn Castro Archives)

While the stereotypical Victorian parlor includes a potted fern perched on a stand, their fronds were a tiny tip of the virtual jungle that filled some interiors of that period. They clustered in window gardens, decked walls, occupied summer fireplaces, formed screens around sofas and flourished in glass enclosures.

In the 19th century, nature was believed to hold the key to emotional solace, religious instruction and natural history education, and for some amateur naturalists, physical exercise in pursuit of unusual species. In the same way that Victorians saw prints of Old Master paintings and religious illustrations as beneficial to children, flowers and foliage were expected to inspire family members and visitors. Their language of flowers interpreted various plants as symbols of devotion, love, sorrow, remembrance or hope.

Typical views were expressed by a writer who spoke of the vegetable kingdom as analogous to human behavior with some industrious and perpetually striving for the good of the whole; the leaves provident for the coming day, the flowers provident for the next generation, all working, not merely for themselves alone. Thus hyacinths, ivy, fuchsia, and numerous other plants meant far more to their owners than colorful decoration.

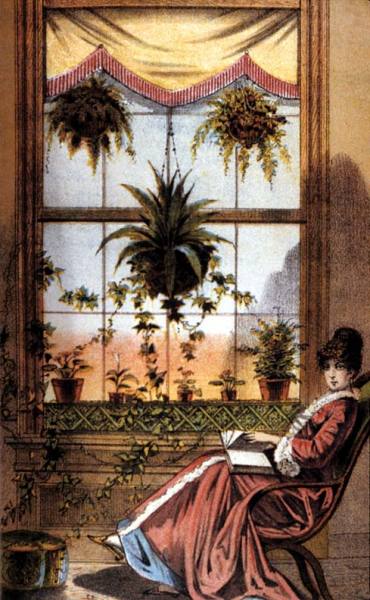

For the thrifty, plants offered an inexpensive means of filling space. Advice manuals frequently decreed that plants in a window were just as good as expensive curtains and finer than anything you can buy. Parlor gardens held particular appeal during long winter months when they provided a cheering bit of green growth, although individual plants might be shifted outdoors during the summer. There was no lack of ideas on how to integrate plants into the parlor.

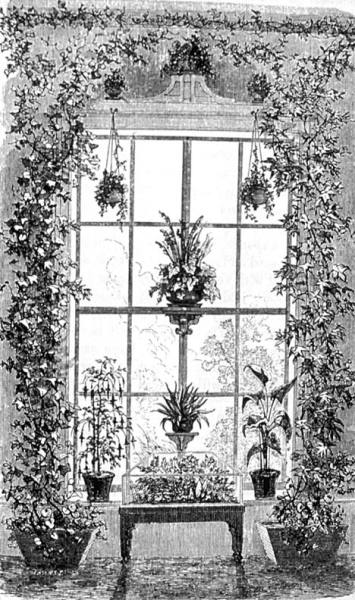

Window Gardens

A common arrangement for a window garden featured a table in the center, hanging baskets, and vines trained to go around and over the window.

Window gardens filled with pots, hanging baskets and trailing vines created a transition between house and garden. A bay window was the epitome of such parlor greenhouses. Most window gardens adopted a symmetrically balanced arrangement featuring a stand or shelves in the center, hanging baskets dangling above, plants on brackets or sills to the sides and often vines trained to grow over and around the ensemble. The vines could originate in hanging baskets, but more often grew from pots placed on the floor at each side of the window.

Plants on Walls

Training vines to crawl around interior elements was a favorite Victorian concept. Walls could be completely covered in ivy, which could survive dim spaces, fumes from gaslights and forgetful would-be horticulturalists who seldom remembered to water plants. Instructions called for placing the roots either in pots of soil or in small vials of water behind picture frames and then encouraging the plants to embrace the frame, outline a cornice, or drape the top edge of a window as a lambrequin (valance). In extreme cases, homeowners used all those techniques. One correspondent to a ladies’ magazine claimed to have grown 60 to 80 yards of ivy, covering all four walls and fastened with loops of thread (in a color to match the wallpaper) and pins or tacks.

Wardian cases could be homemade, but many homeowners preferred to purchase them in one of the many revival styles available, with or without accompanying stand.

Wardian Cases

Any child who ever placed plants in a plastic bottle, sealed the bottle, and hoped for a tiny self-sustaining ecosystem has made a type of Wardian case. Wardian cases—named for their inventor, Nathaniel Ward—were small, self-maintaining environments. The idea was that once the plants were sealed inside with a little water, natural processes would recirculate moisture and keep the plants growing without further human intervention. (This was revived as the terrarium fad in the 1970s.) Scientists greeted the 1830s invention with enthusiasm because it made possible shipment of exotic plants from far-flung corners of the globe. Homeowners saw these cases as a golden opportunity to make small indoor gardens that required little care. During the fern craze of the mid-19th century, many people rushed into the woods, dug up every fern they saw, and installed them in Wardian cases.

Instructions on how to build a basic case abounded, but it was also possible to purchase elaborate cases in styles from Rococo Revival to Gothic Revival. One could either simply place the case on a table, acquire a special stand, or buy an integrated case and stand.

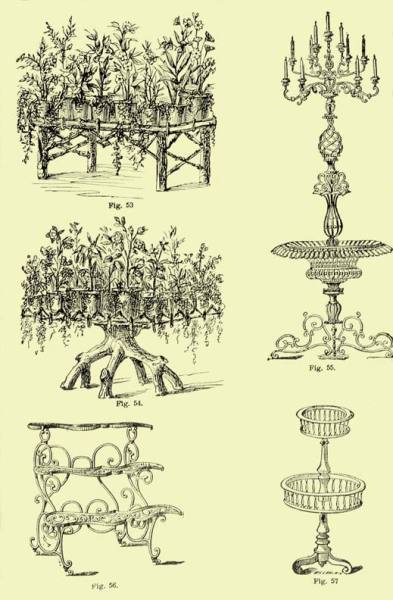

Containers and Stands

Plant stands abounded in an array of materials and styles, often multi-tiered and some including fishbowls, fountains, birdcages, or candelabras.

Nineteenth-century advice manuals brimmed over with inspired ideas on how to pot plants. Homeowners could buy planters ranging from relatively plain to nearly any revival style they might desire, but they also pressed coconut shells and gourds into service as containers. Purveyors of do-it-yourself instructions recommended a vast variety of materials with which to personally decorate the cheaper pots, such as gluing seeds and pine cones in patterns.

Practically any material could be used for plant stands; metal and wicker saw extensive use. Elaborate stands constructed in tiers (and sometimes in triangular configurations for corners) could hold several plants. In the most complex designs, the ensemble included fish bowls, fountains and bird cages.

Summer Fireplaces

Just like homeowners today, Victorians puzzled over what to do with a fireplace during the summer. When left alone it was a black hole in an otherwise elaborately decorated room. Mini gardens offered an appealing seasonal alternative to a fireboard or fan. These small arrangements ranged from boxes of soil set into the cavity and filled with plants, to collections of pots arranged within the space, to elaborate compositions of tree stumps and branches adorned with plants (and occasionally decorated with stuffed squirrels or preserved butterflies).

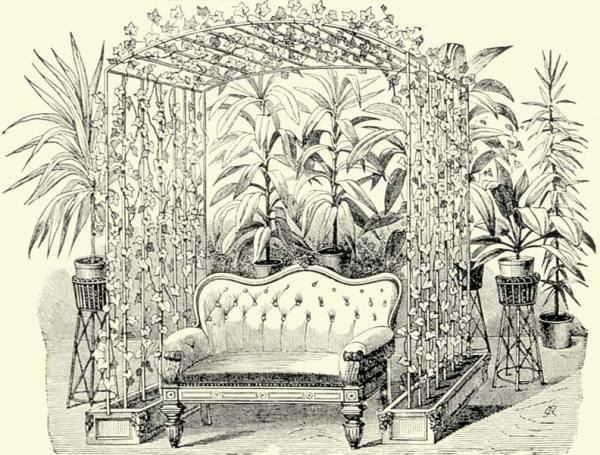

The most extreme arrangements incorporated vine-covered trellises surrounding a sofa. Backed by yet more plants, they gave the impresson that the furniture was being engulfed by a jungle.

Trellises

Most of us associate trellises with exterior gardens, but to the 19th-century plant fanatic they seemed like perfect interior screens. Usually, latticework rose from behind a rectangular box planted with vines trained to grow up and cover it. In more dramatic cases, trellises flanked and then roofed over a sofa. With additional potted plants as part of the ensemble, the viewer saw the seating (and any occupants) as being engulfed in foliage. One glance at some of these compositions and it is easy to understand garden designer Gertrude Jekyll’s comment that I have seen many a drawing room where it appeared to be less a room than a thicket.