ABOVE: Penelope Creeley’s family transformed this fire station into their home; the tower at the rear of the building, once used to drain fire hoses, became her kids’ favorite hangout.

After moving into a new home, you’ve likely never had to ask yourself which end of the hayloft should hold the pool table, or whether a choir balcony will fit two twin beds or one. You’ve probably never shopped for kitchen fixtures in a railroad yard, either. But others have.

Lured by the frisson of experiencing something unique—or maybe just enticed by the idea of challenge on a really big scale—some old-house lovers forsake the world of the predictable to follow a different path to architectural bliss: by buying, living in, or restoring old buildings—barns, churches, schoolhouses, fire stations—that were never meant to be homes.

“The first thing we said was, ‘It’s a castle!’” jokes Jennifer McTernan, recalling the moment when she and her family laid eyes on the 1897 brick building they now live in, which began life as a Roman Catholic church. “It just seemed so perfect.”

The idea of adaptive reuse—taking over a public, religious, or commercial structure and turning it into a livable home—is not new, and it’s not always the best answer: Many preservation standards maintain that structures are better served by remaining true to their original purposes. But when buildings have outlived their intended purpose—and as the world grows more aware of the environmental impact of new construction—the idea of transforming structures from underused curiosities into beloved residential spaces strikes some as practical, if not downright trendy. Those who have done it say it’s not easy—but that it’s a process so rich in its own rewards that it amply pays back the time, money, and effort involved.

1. Before taking the plunge, get expert advice.

Solid construction made the Callahans’ barn ideal for transformation into a house.

When Donna and Joseph Callahan were looking to move from the city to the country with their expanding family, they took a drive and spotted a hulking 4,000-square-foot barn. The massive size of the unfussy clapboard building—which was no longer needed for livestock, and thus a potential target for teardown or vandals—caught their eye, as did its prime position on two acres of rolling farmland. The Callahans weren’t deterred by the fact that the late 19th-century building had recently been a working stable, filled with cows and horses.

After tentatively agreeing to buy the well-worn barn for $7,000, the couple decided to check their instincts with objective advice. Not knowing any renovation experts, Donna called an architect and described their plan.

“He said, ‘Stay away from barns; they are very unstable, they warp,’ and on and on,” remembers Donna. “I was thinking, ‘Oh no.’ Then he asked me where the barn was, and it turned out that he lived nearby. He said, ‘The Schmidt barn! I love that barn!’” With that, the matter was settled, and the Callahans signed on the property.

The moral of the story is twofold: There are exceptions to every rule, but it’s best to check your gut against some expert views. “You can have a vision,” says Donna, who still lives in the barn today, “but check it out with somebody first.”

Passersby might mistake the McTernan abode for a regular church, but inside, it’s a comfortable family home.

2. Take a chance on a dream.

When the McTernan family first toured the spire-topped, Gothic-style Catholic church, they were impressed with the enormous, 75′-long hand-dug basement and stained-glass windows, which glow in mellow tones of amber, violet, and pink. They also loved the unfinished choir loft—picturing twin beds for their two daughters there—as well as the tile roof and time-softened red brick exterior.

For Jennifer, who had grown up near the church in Angola, New York, the historic appeal of the building—at once imposing and intimate—sealed the deal. She had loved the church as a child; returning to the area as an adult, she jumped at the chance to own it, following in the footsteps of previous owners, who took over the empty building decades ago when its congregation moved on to larger digs.

“To me, it’s history,” says Jennifer. When given the chance, in other words, you act—because some buildings only come around once in a lifetime.

3. Prepare for plenty of work.

Moving into a non-residential structure means signing on for all sorts of repair and conversion projects to make the place workable as a house. Plumbing and lighting can be issues that take time, thought, and money to solve; so can drainage and dampness in basement and garage areas. “Keeping that slate roof in order was a pretty major investment,” says Penelope Creeley, who, with her late husband, converted a 1912 brick fire station in Buffalo.

The Creeleys divided the fire-truck garage and horse-stabling space on the bottom floor of the building into a study, a mudroom, a bedroom and bathroom, and a two-car garage for their own vehicles; the upper floors became the kitchen, bedrooms, and more living space. A tower once used to drain fire hoses was repurposed as a hangout for their children.

The Callahans filled their barn with salvaged finds, including industrial signage.

For their barn project, the Callahans had to add several bathrooms, as well as fashion interior doors and walls to divide the large first floor—adding barn doors to divide a living area from a parlor, for instance. They also realized, in carving out a kitchen, that a second set of stairs to the upper-level bedrooms would be handy; because the first floor of the barn did not lend itself to a traditional staircase, they instead cut a hole into the ceiling above the kitchen and installed an iron spiral staircase salvaged from an old Purina mill.

4. Embrace the imperfections.

Living in an old building means learning to accept, and even appreciate, the scars left by time. Because it began life as a carriage house for a grand Lake Erie estate, the Callahans’ barn was constructed out of better-than-typical materials, but by the time the family bought it, the original heart-pine floors had been pitted and gouged by countless hooves and heavy equipment.

Still, Donna never seriously considered replacing the floors, or even repairing the holes. The boards that had completely deteriorated were replaced with patches, but the only other treatment they got was a good scrubbing. “Our barn is old, but it’s very sound,” she says. “People built them to last.”

5. Treasure vintage material.

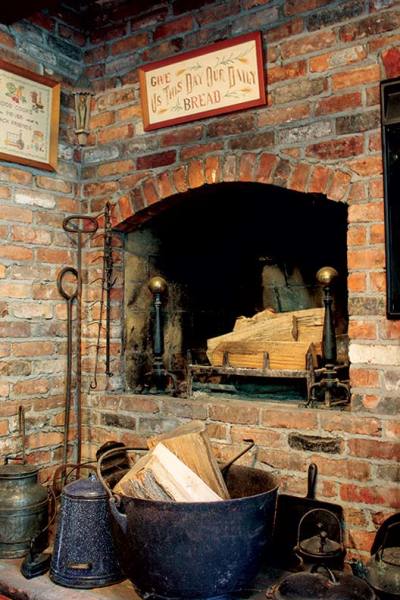

In their kitchen, the Callahans constructed a hearth out of bricks they’d saved for years before moving in.

When one of the two towering steeples on their church had to be taken down after being damaged by weather, the McTernans saved most of the old roof tiles from the spire. It was a tough job collecting and storing them, says Jennifer, and they still haven’t been used. But the next time roof work is needed on the building, the McTernans won’t have to hunt fruitlessly for the perfect replacement tiles.

Even material you don’t immediately see a purpose for can come in handy. Before she ever laid eyes on her barn, Donna Callahan had started stockpiling bricks. Her husband would bring home piles of them from demolition sites—a row house once owned by Mark Twain; a Catholic church that had stood across the street from where Donna grew up—and she would clean them and store them in her basement. When the couple moved into their repurposed barn, they used the stash of bricks—all 4,000 of them—to build a custom fireplace and hearth for their new kitchen.

6. Adjust your scale.

When you live in a space that was created to hold items like hay bales or fire trucks, you need to recalibrate your sense of scale. In many cases, this means thinking bigger.

In the cavernous barn repurposed by the Callahans, the sheer scale of the interior spaces—including a hayloft that can hold beds, an antique oak bar, and a pool table, as well as a tack room that became an open-plan kitchen and breakfast room—lent itself to a decorating scheme that incorporates commercial and industrial signage and equipment. The iron pot rack in their kitchen was a massive piece thrown out of the railroad depot at Buffalo’s Central Terminal.

“We could always buy the larger things,” says Donna. Indeed, with an unusually sized or shaped home, you just might put yourself in the market for décor that is truly unique.

Religious artifacts abound in the McTernans’ home, including stained-glass Gothic windows and an original altar rail.

7. Consider the logistics.

There are downsides to living in an adaptive home, often where simple logistics are concerned. Inside the McTernans’ church, chandeliers hang 17′ off the floor, making lightbulb-changing a challenge. Ladders are a good investment, they’ve found, as are extension poles and mini-scaffolds.

In the Creeleys’ firehouse, Penelope hired an architect to help her create an office and a master bedroom suite. Work on the firehouse was done with as much sensitivity to its history—and its place in the surrounding Black Rock neighborhood in Buffalo—as possible. Because the inside of the brick structure was dark, Penelope wanted an expert to help bring light into the space. “It wasn’t much of a consideration in the original firehouse, that light get into where they stored the trucks,” Penelope says. “But light considerations in these building adaptations are very important.”

Along the way, homeowners who have adapted nontraditional buildings into homes have learned an important secret to making such logistics flow smoothly: Choose carefully when hiring contractors. “Just about everything you did to it was a big deal,” Penelope says of the firehouse. “Tradesmen would get nightmares looking at it.”

Jennifer McTernan soon learned this helpful trick: Start every conversation with a potential contractor by talking about the home’s uniqueness. Tell them right away, she says, that “this is not a house.”

Online bonus: Do you live in a repurposed building (or just want to?). Join our special discussion group on MyOldHouseOnline.com.