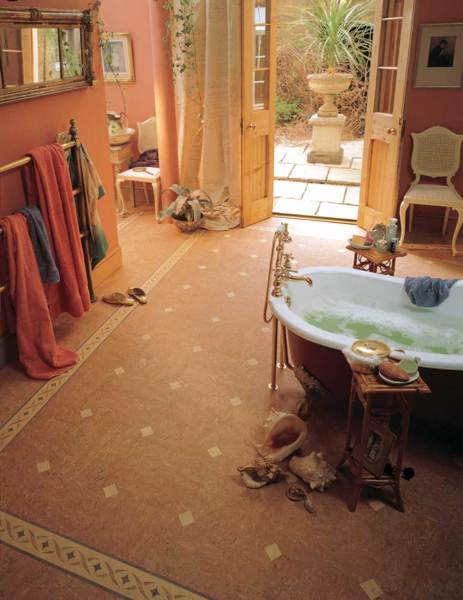

Rubber sheet flooring can be inlaid with interesting designs, such as the border and corner accents shown on this custom installation by flooring designer Laurie Crogan.

Germs. They’re the reason resilient flooring became popular near the turn of the 20th century. The Victorian era was coming to an end, and new theories about germs were gaining ground, causing homeowners to start looking for easy-to-clean surfaces that wouldn’t let those pesky microorganisms linger inside their houses. Marketing materials from the time made the case for removing the carpeting so popular in Victorian decorating schemes and replacing it with hard-surface flooring. “An old-fashioned floor covered with carpet closely tacked down around the edges is a very unsanitary thing,” warned a 1919 brochure promoting oak flooring. “It catches dust and germs which penetrate under the carpet and can not be removed by sweeping…every footfall lets loose a little cloud to poison the air we breathe.” While hardwood flooring was one solution for the times, resilient flooring materials like linoleum, cork, and rubber had the additional selling points of being cheaper to install and easy to maintain, and were being marketed by a new wave of companies.

Today, cost, authenticity, and maintenance are just some of the considerations that go into restoring old-house flooring. Another big factor for many homeowners is a product’s environmental impact, and that’s an area where today’s resilient flooring also scores well.

Of course, resilient flooring is appealing in other ways, too—it’s easy on the feet, offering a little bounce to your steps around the kitchen, and provides soundproofing qualities to boot.

Linoleum’s water resistance and natural antimicrobial properties make it a good fit for use in bathrooms.

Courtesy of Forbo

Linoleum

Linoleum was invented by Frederick Walton, an Englishman who began experimenting with the rubbery skin that formed on an old can of oil paint, and eventually perfected the formula for the durable floor covering, which draws its name from the Latin words for two of its ingredients, flax (linum) and oil (oleum). Walton opened a linoleum manufacturing facility near London in 1864, and within a decade, the product had taken off in Europe and inspired copycats. “Linoleum may have been the first product to become a generic term, followed later by such favorites as Kleenex, Jell-O, and escalator,” writes Jane Powell in her 2003 book, Linoleum. By the early 1900s, linoleum’s popularity had jumped the pond, and manufacturing giants like Armstrong were marketing it for all rooms of the house. It proved particularly popular in kitchens and bathrooms because it held up to wear and tear, was water-resistant, and bore natural antimicrobial qualities from the linseed oil used in its manufacture. The material was so durable, in fact, that it was used for a time as the standard flooring on U.S. warships. A 1935 Congoleum-Nairn brochure touted their Sealex Battleship linoleum as being “manufactured to comply in every respect with the exacting requirements of the U.S. Government.”

Early linoleum came in solids, multicolored designs resembling granite and marble (usually bearing names like Marbelle), and Jaspé, which had striated lines. It didn’t take long, though, for everything from geometrics, florals, and splatters to faux ceramic tile, Persian rugs, wood, and brickwork to become available. During the 1930s, elaborate inlaid tile patterns became popular, which were created by cutting different colors of linoleum and inserting them, like puzzle pieces, into a solid-colored field. These included borders (Greek key, laurel leaf, and ribbon swirls, for example) and small stand-alone designs placed at room corners, or large ones in the center of the kitchen or bathroom for dramatic effect. At the time, a large selection of inlays was available (via a special manufacturing process) straight from the factory.

Though we don’t have the same variety of designs available off the shelf today, you can still create inlays on sheet flooring with a little schooling. One California artist, Laurie Crogan, has been quite successful at reviving the art of elaborate, inlaid custom linoleum floors. Regardless of the design on your linoleum floor, they’re now easier to care for than ever before. “Today’s linoleum floors come with a factory- applied high-performance coating that means you don’t have to do the maintenance—waxing and stripping—of years past,” says Bill Freeman, a consultant to the Resilient Floor Covering Institute. Linoleum is—and always has been—made from raw ingredients that are renewable, so it’s an environmentally friendly product, which is also a big selling point. “The basic materials from which linoleum is made—linseed oils, dessicants, resins, wood flour, powdered cork, ground limestone, pigments, and jute fabric (burlap)—are all renewable, and obtained without major environmental impacts,” Powell notes in her book.

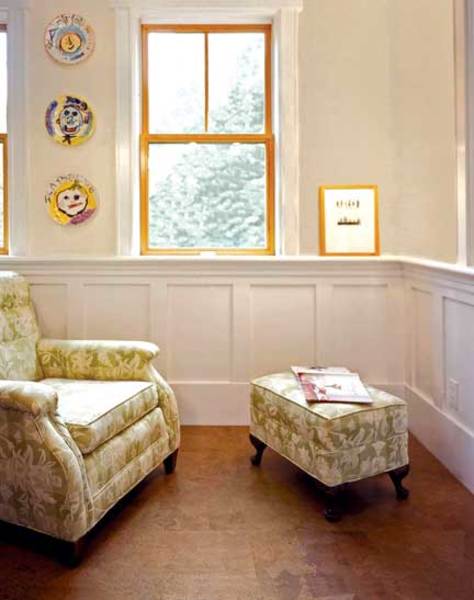

Cork floors resemble wood, but with a more intricate graining pattern.

Courtesy of Wecork

Cork

While cork flooring was offered at the beginning of the 20th century, it hit its residential apex during the 1930s, when great modernist architects—like Richard Neutra and Walter Gropius—used it in their own houses. Throughout that decade, it was marketed as a terrific product for residential use. A 1930 Armstrong Cork brochure titled “Cork, Its Origins and Uses” put it this way: “(Cork) is coming to be more and more used…in private homes every year, for it has all the necessary beauty and service features that the modern home requires, plus a degree of comfort and warmth that few other floors possess.” The same brochure hawked cork tiles in three different colors—chocolate brown, honey amber, and pale flax—natural shades that, the brochure explained, resulted from different baking times.

Warm, earthy colors have long been part of cork flooring’s appeal, as has the fact that it has always been made of renewable materials. Pure cork, baked in molds under pressure, was the entire formula in the 1930s, and while today’s process may involve some added materials, it continues to be a natural, sustainable product, harvested from the regenerating bark of cork trees. Cork can mimic wood floor installations, but with more interesting graining patterns. Another bonus unique to cork is its warmth—step on it in bare feet, and it won’t shock your feet like cold stone; in addition to its bounce, it always feels slightly warm to the touch.

Cork has a long history of being the flooring of choice for decades in public buildings like schools, museums, and churches due to its sound-deadening qualities. This characteristic made it popular to use in the dens of private houses in the 1940s and ’50s. “In terms of acoustical qualities, cork rates the highest—it’s very quiet,” says Freeman. “Back in the 1950s, one of the biggest marketplaces for cork was in college libraries.” But, he adds, you want to be careful of where you install it, because of the three historical resilient flooring types, cork is the least impervious to moisture. When used in areas where water and dirt will get tracked across it continually—say the front entryway of a public building—it won’t hold up as well as installations of rubber and linoleum. Today, however, you can buy cork mosaic floors—created from recycled wine corks and resembling pennyround tiles—which can be sealed upon installation and which are marketed as being great for use in wet areas like saunas, showers, and pool surrounds.

Rubber

An original rubber kitchen floor in Washington, D.C.’s Anderson House, built in 1905, shows how early tiles fit together like pieces of a puzzle.

Jessica Salas-Acha

The story of rubber flooring begins in 1894, when the famed Philadelphia architect Frank Furness patented a system of interlocking 2×2 rubber floor tiles. Furness designed them for use in high-traffic train stations (places like his later masterpiece, the Amtrak station in Wilmington, Delaware), but they also saw some use in high-end houses of the day, one example being Washington, D.C.’s Christian Heurich Mansion (1894). The earliest rubber floor installations consisted of tiles that hooked together like oversized puzzle pieces.

By the 1930s, the material had evolved into square tiles, and was being heavily marketed for use in private homes. A circa-1930s Stedman Rubber Flooring Company brochure called “Modern Floors for Modern Homes” declared it, “original and unique. From the day it is installed, all who come into contact with the floor are conscious of its restful, resilient comfort under foot, its colorful appeal to the eye, and its solidarity of structure which indicates the permanence of the material.” The same brochure highlighted tiles in 30 different colors, most resembling granite or marble, which were available in 10 different sizes, from 3×3 to 12×18.

While rubber was probably the least traditionally popular of the three resilient flooring materials, a great effort was made to position it as a manly material in early advertising campaigns. “The man of the house must not have to worry about tracking in mud, dropping his golf clubs in the corner, or an occasional live ash from a pipe or cigarette,” noted the same Stedman brochure. “But he does want a floor to be good-looking, and to stay good-looking without having to do much about it. So Stedman Reinforced Rubber tile is a natural choice because it resists dents, mars, and burns, never wears out, and is easily taken care of.”

Rubber flooring today, of course, is considered so easy to maintain that it is commonly used commercially. It is available in a wealth of colors, and can be purchased in versions made from either recycled materials, or raw rubber.