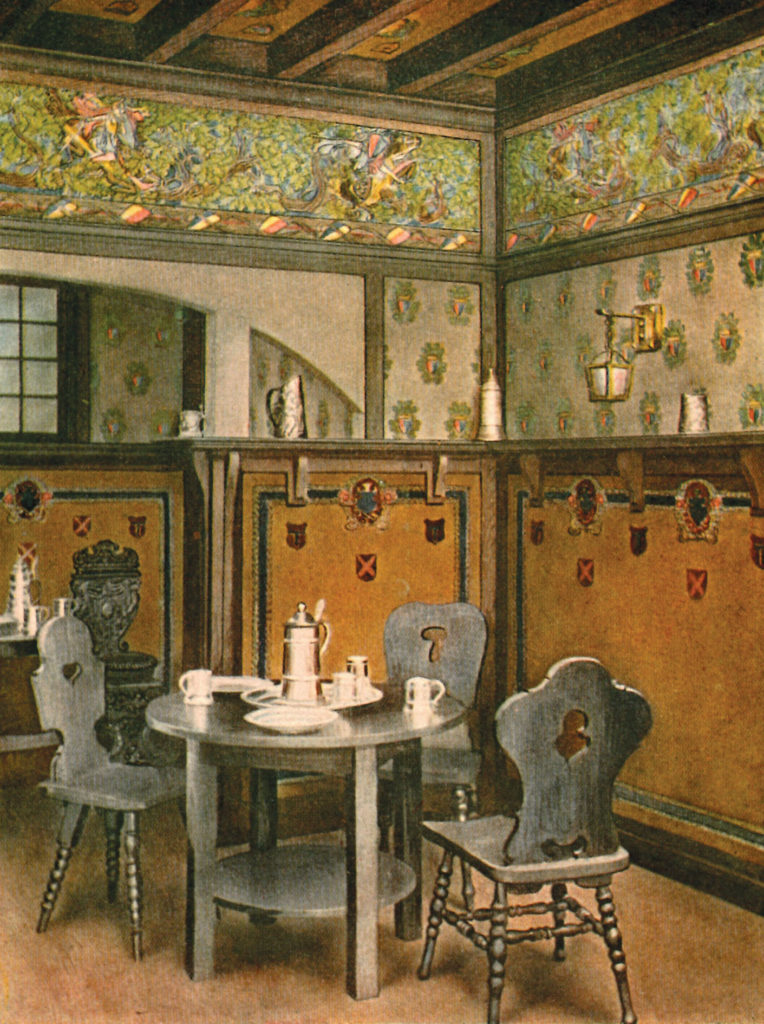

A hand-painted, panoramic frieze based on the work of English Arts & Crafts designer Moyr Smith adds color and interest to this Aesthetic Movement conservatory. Courtesy Historic New England

Foreign travel was difficult in the 18th century. Those who did not venture afield would pay a small fee to view dioramic or panoramic spectacles: viewers sat in the middle of a room while scenes painted on screens were rolled in a circle around them, giving a 360° impression of an exotic locale. Thus inspired, French wallpaper manufacturers created similar panoramas to paste on walls. With scenes of Roman ruins, Mount Vesuvius erupting, tropical birds and toothy crocodiles, these papers transformed ordinary rooms. They held lessons on geography and history, depicting mythological stories, military campaigns, and daily life in faraway lands.

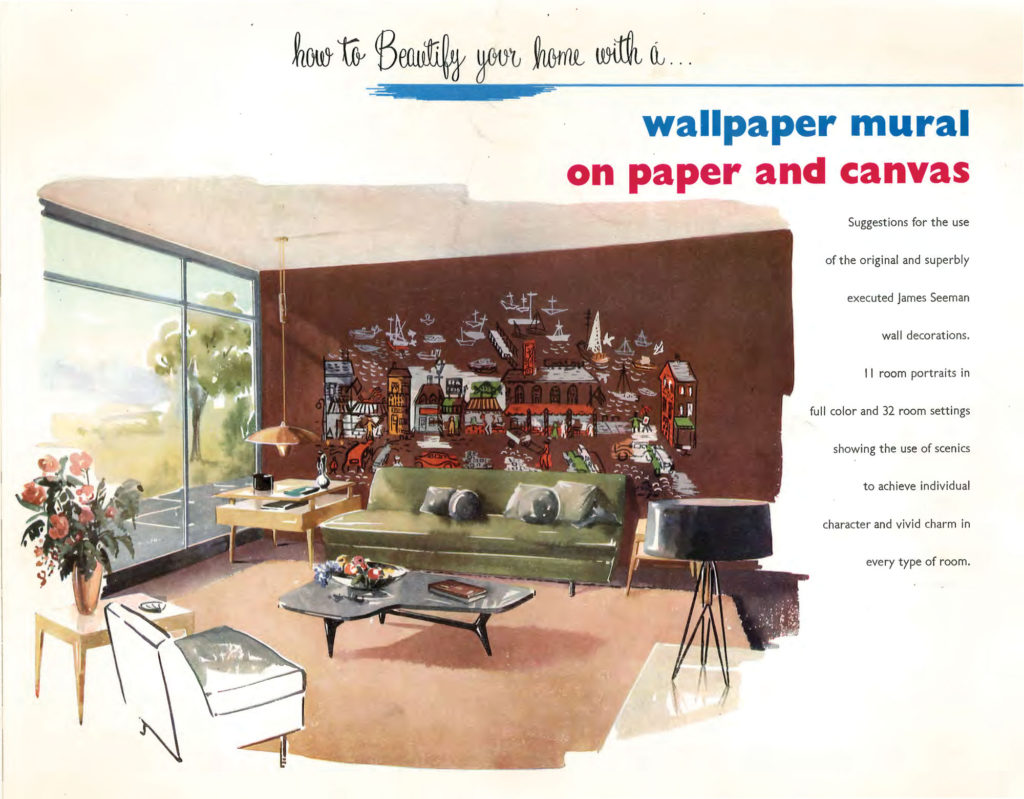

Panoramic wallpapers were hung in entry halls, dining rooms, stairwells, sometimes living rooms—sparsely furnished spaces with broad expanses of wall. Narrower murals in friezes replaced floor-to-ceiling papers as ceilings were lowered in the 20th century. Designers today sometimes frame a single panel of hand-painted or –printed wallpaper.

‘Les Zones Terrestres’ by Zuber is an exotic background in this Tribeca loft. below Brilliant green and a subtle Chinoiserie design mark de Gournay’s ‘Earlham’, hand-painted on dyed silk. Architect ma/d Mckay; designer Samantha Crasco

The Chinese, who invented paper 2,000 years ago, produced wallpaper for export to the West starting in the early 17th century. Hand-painted with water-based gouache or tempera on joined sheets of mulberry paper (or silk), these papers were vividly colored and naïve in perspective, with background figures often as large as those in the foreground. Pagodas, fishermen, and snow-capped mountains were softened with delicate birds, butterflies, and lotus flowers.

Courtesy Peter Lalor

French panoramic or scenic wallpapers—the terms are interchangeable—stole the show when they were introduced in the late 1790s. San Francisco Airport Museum Curator Nicole Mullen explains that durable paper made from linen rags was pasted together to form long rolls, which were then coated with Flanders glue in a process called grounding, which stabilized each color as it was added. Printing blocks were carved from fine-grained pear wood. A paper might need a few hundred to several thousand blocks; rolls were usually eight to 10 feet long and 20 inches or more wide, and a scene could take from five to more than 40 panels. Lithographs of the completed panoramas were made for buyers to preview. The most famous scenic wallpaper manufacturer was Frenchman Jean Zuber, whose factory opened in 1797. It took 20 engravers several years to produce their first paper, ‘Views of Switzerland’, in 1804, using 1,024 wooden blocks and 95 colors. Jim Francis and John Nalewaja of Scenic Wallpapers explain that Zuber was known for exquisite detail, creating 25 panoramic scenes between 1804 and 1860. Other contemporary French companies include Dufour, known for large panoramas and expressionistic clouds; the firm closed with Dufour’s death in 1827. Zuber still produces their iconic papers today, at the original factory, a French designated national historic monument, which holds 130,000 documents and 150,000 original wood blocks.

The China Trade Room at historic Beauport in Gloucester, Mass.

Hand-painted Murals

Earlier householders who could not afford expensive, imported silk panoramic papers often chose a hand-painted mural instead. In Colonial America, itinerant painters (the most famous being Rufus Porter in New England) worked throughout the Colonies, painting panoramas and scenes of local life that would become important documentation of the times and culture. Whether primitive, sophisticated, or contemporary, custom murals have never lost their appeal and remain a popular alternative to panoramic papers today.

Chinoiserie: Scenic Chinese Wallpapers

The Chinese began producing “wall papers” for export in the early 17th century. Shown above is The China Trade Room at historic Beauport in Gloucester, Mass., with hand-painted Chinese wallpaper imported to Philadelphia in the 1780s, never hung, and installed here in 1923.

Fromental’s panorama on silk was inspired by the fairytale drawings of Hans Christian Andersen. Courtesy Fromental

SCENIC PAPERS TODAY

A.L. Diament & Co.: Antique, never-hung, French wood block-printed mural wallpapers

de Gournay: Hand-painted Chinoiserie and panoramic French scenic wallpapers; Asian, eclectic, and custom designs

Fromental: Handmade, embroidered and painted silk papers, Chinoiserie to contemporary

Gracie: Chinese, Japanese, European, and American hand-painted scenic papers in many genres

Griffin and Wong: Hand-painted, silk Western scenic and Chinoiserie papers based on historic designs

J.R. Burrows: ‘Willow Pond Scenic’, an American design ca. 1910 with a 21″ drop-match repeat

Paul Montgomery: Fine, hand-painted panoramic silk-paper panels and murals in multiple genres

Zuber: Scenic papers hand-printed from original wood blocks 1797–1870

The classicism of Zuber’s ‘Les Lointains’ (1825) is a romantic backdrop for antique and modern furnishings in the dining room of actor Brooke Shields’ townhouse.

What is Grisaille?

Grisaille is a method of painting, done in shades of grey, meant to imitate classical sculpture. Old Masters such as Rubens used grisaille as a practice exercise before executing a fully colored painting. Grisaille panoramas lend a classic presence to a room, as shown in this Manhattan townhouse dining room hung with Zuber’s ‘Les Lointains’.

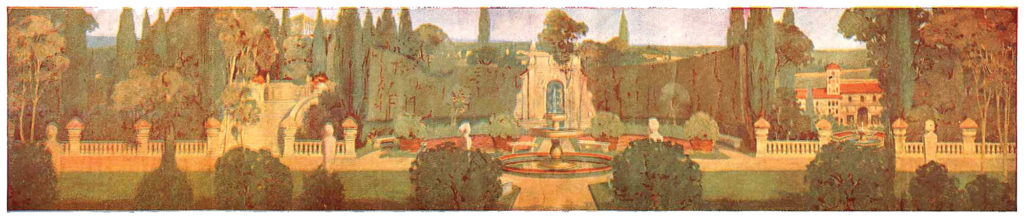

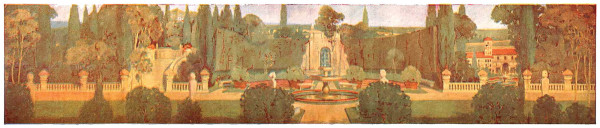

San-kro-mura mural #308 depicts the Villa Medici; six sheets made a 30’ repeat. Courtesy Peter Lalor

An Archival View of Scenics

With machine printing, wallpaper was readily available, and expensive hand-blocked panoramas fell out of fashion. The Victorian tripartite division of walls into dado, fill, and frieze dealt a blow to floor-to-ceiling panoramas. Scenic friezes came back during the Arts & Crafts era, when peaceful woodlands, flying geese, and sailboats decorated artful dining rooms and libraries; neoclassical panoramics returned for Colonial Revival homes. Bo Sullivan of Bolling & Co. points out that American watercolorist Charles E. Burchfield designed ‘Country Life and The Hunt’ for Buffalo-based H.M. Birge & Sons in 1924. Cleveland’s Schmitz-Horning Co. sold the San-kro-mura line of washable scenics after 1900, with such popular themes as automobiles, pastorals, and the Wizard of Oz. (Though San-kro-mura sounds vaguely Japanese, it’s really a contraction of the words sanitary, chromatic, and mural.)