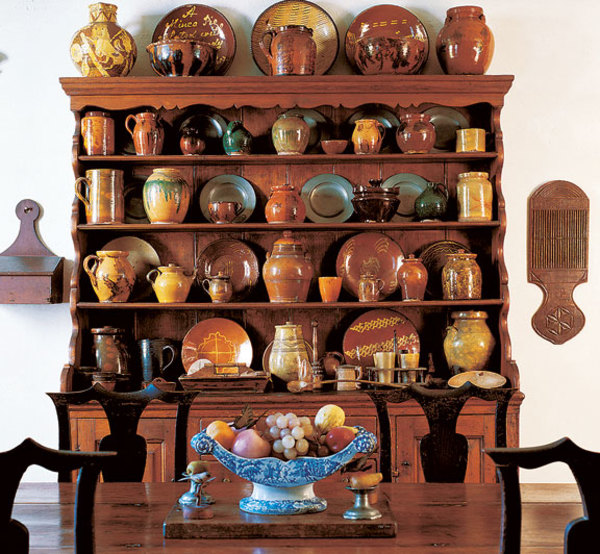

Redware fills a dresser at Cogswell’s Grant, an 18th-century farmhouse with a large folk-art collection. (Photo: Sandy Agrafiotis)

Artisans today are producing wares stunningly similar to the originals, using old techniques and materials. The new pewter is lead-free and food-safe, a great benefit. And companies like Spode and Mottahedeh issue china patterns already familiar more than 200 years ago.

The earliest colonists used a combination of treen and pewter, the latter imported from England. Almost from the first settlement, regional potteries, using the local clay, produced serving ware, plates, even lamps. The color and decorating motifs of redware—a continuation of a European peasant tradition—varied depending on whether it was made in the Hudson Valley, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, or Ohio.

Silver was imported and later produced here, and several pieces would have found their way into even modest households, as heirlooms or wedding gifts. Chinese export porcelain came from England; every household coveted a few pieces. By the 1750s it was so popular it had its own import tax. Creamware was invented in 1767 by Josiah Wedgwood in England, as an affordable stoneware alternative to Chinese hard-paste porcelain. It and related stonewares were soon made in America as well, particularly in Philadelphia. After 1784, transfer-printed clay goods mimicked China ware; the famous ‘Blue Willow’ was introduced in 1790, and ‘Blue Italian’ in 1816. Inexpensive, factory-made tableware was available from the 1830s onward.

Pottery Glossary

Blue-and-white porcelain: Porcelain paint-decorated with cobalt blue, developed in China by the 15th century, later popular in England and the Colonies.

Canton: Porcelain named for the Chinese port city where the East India Co. traded for European export in the 18th and 19th centuries. Much porcelain arrived unpainted, its decoration applied in Canton’s enameling shops; thus Canton suggests a 19th-century export-specific porcelain. Butterflies, flowers, and so on are painted on a celadon ground.

Creamware: Lead-glazed earthenware with a light body, a substitute for Chinese porcelain perfected in Staffordshire, England, ca. 1750, with pierced, molded, enameled, or transfer-printed designs.

Ironstone: Heavy “stone china” dating to the 1740s but popularized after 1860.

Lustre: A surface sheen deposited on pottery or porcelain by firing metallic pigments.

Mocha: Cream- or pearlware decorated with vibrant-colored bands into which tree-like (dendritic) or other effects are introduced. Used in taverns and home kitchens. Named after mocha quartz.

Mochaware by Don Carpentier

Pearlware: A whiter creamware with a nacreous glaze, introduced by Josiah Wedgwood about 1779.

Porcelain: Translucent, vitrified ware made of china clay and china stone fused at great heat.

Pottery: Generally speaking, any receptacle or vessel made of clay by a potter. The term usually refers to earthenware fired at low temperatures, as distinct from stoneware and porcelain.

Redware: Historically, lead-glazed wares of a soft, porous body ranging in color from buff to red to brown. Often decorated with folk motifs.

Transfer Printing: An affordable way to decorate pottery and porcelain: An impression on paper is taken of an inked, engraved metal plate, and that impression is applied or transferred to the glazed object. At firing, the printed pattern sinks into the glaze. Transfer printing began in England after 1753.