Chris Christou holds a pair of 1880s Fuller-ball faucets—now with rebuilt internal working parts.

For an industry where you’re better off replacing it with new comes close to a mantra, George Taylor Specialties certainly bucks the trend. A renowned resource in the metropolitan area of New York City, this family-owned-and-operated company has been breathing new life into century-old faucets and valves, as well as making and selling reproductions, for more than two generations. After featuring their work on many projects in Old-House Journal since the 1980s, we jumped at the chance to visit Chris, Valerie, and John Christou in their Manhattan showroom and shop to learn more about the arcane art of keeping antique faucets in working fettle.

What’s Possible and Practical

What the folks at George Taylor Specialties say they service most in their business are sink faucets and valves. Clawfoot tub faucets, while they may last no longer than sink faucets, can be replaced fairly reliably with one of the many good reproductions on the market, says business manager Valerie. In the same way, it’s often possible to change out a shower body for new hardware, retaining the original trim rings and handles, without upsetting the appearance of the whole bathroom. Antique lavatories, sinks, and basins are another matter. Style aside, very often the faucets or valves are made for the fixture—particularly the critical dimensions such as hole diameters and spread (the hot-to-cold pipe distance) and cannot be retrofitted with modern hardware. Abandoning the hardware then means abandoning the fixture as well, and that can have a dramatic impact on the integrity of the bathroom.

When these beautiful antique swan’s-neck tub faucets needed to be relocated, George Taylor Specialties machined the 24″ extensions to connect them through a wall.

While repairing or rebuilding a vintage faucet is likely to cost more than buying a reproduction unit, it may be more practical than replacing the entire fixture—especially if it is one of the many obscure or collectible designs or parts that abound in pre-1940s plumbing hardware. The working parts that the Christous see fail most often are the valve seats and stems in compression faucets, the workhorse design in wide use for more than 90 years. Under normal use, the washer loses its sealing ability as it ages and needs to be replaced. If it is neglected, however, water will leak past the washer, eroding part of the seat, which will then have to be replaced (if it is the threaded, removable type) or resurfaced (if it is part of the faucet body). Forcing a leaky faucet shut can bend the stem, strip the threads, or break parts.

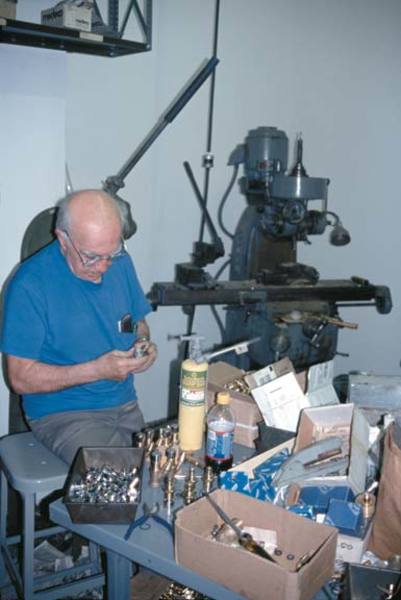

If you think that being in a specialty industry means making countless new parts, you’re wrong. “We never make something we can buy,” says president and patriarch Chris. “It becomes too expensive. The key is having good sources of supply—valve seats, for example, from firms who specialize in just seats.” If the customer’s pocketbook and needs allow, however, Chris and John can re-create the part originally made from round or hexagonal stock in the machine shop.

Among the specialized products George Taylor Specialties manufactures are hundreds of spring-loaded valves for drinking fountains in New York City parks.

When the economics or aesthetics make sense, the folks at George Taylor Specialties will go even further. A stripped valve stem on a J.L. Mott valve is a typical complex job. Because the inside thread is all but destroyed, Chris will rebuild the thread by first building up the metal with silver solder. An expensive but very strong solder used in jewelry making, it bonds to the brass as if it were the same metal. When he has the bonnet cavity built up, he then rebores the stem hole and retaps the thread. Even this process is not as simple as it sounds. This valve stem has a double thread—two threads running inside each other similar to the double helix structure of a DNA molecule. This thread, typical for a lever faucet, allows the stem to close in less than a full turn. (Some old faucets have triple threads.) Chris and John also keep rubber and polyurethane sheets on hand for making washers for nonstandard parts.

A Handle on Restoration

What’s their advice to owners of antique plumbing? “If it’s working okay, don’t touch it!” chides Chris. “Brass has a practical life of about 50 years, and any plumbing older than that—be it faucets or even pipes—is living on borrowed time.” Old brass, he notes, becomes brittle through structural changes in the metal itself.

Note the toothed base on this five-point Crane handle, as well as the characteristic long faucet body with new stem.

John agrees with the basic concept, but is more sanguine about taking action. If old-house owners have faucets—especially handles—that are porcelain, he recommends attending to repairs and maintenance right away. He explains that unlike modern porcelain, which is low-fired, earlier plumbing was made with high-fired porcelain that can shatter like glass. Trying to make a stiff or leaky faucet operate by using excessive force stresses the metal parts, and it can cause old porcelain handles to break, especially if they have a hairline crack or two. The result is not only lost handles, but also potential harm to the user from sharp broken edges. (John recounts tales of hotels that replaced their porcelain faucet handles by the hundreds to avoid insurance liabilities.)

Suppose you’re missing a handle or two already. How do you begin the search for a match? “All porcelain handles are held to the valve stem with a screw; 99 percent of the time the screw is on the side of the metal base, but it can also be on the top under a button or metal plug that you pry off,” says chief technician John. Like so much with old houses, the mechanical connection between stem and handle is far from standardized. Some are square, some have teeth, some are tapered; even popular brands like Standard had several patterns. Nonetheless, a proper, tight fit is all important. It is this connection—not the screw—that carries the torque of turning the faucet. The screw merely keeps the handle from falling off. A screw on a sloppy handle will shear in half.

If there is a bright side to the needle-in-a-haystack search for matching faucet handles, it’s that old stems are generally slightly larger in diameter than modern faucet stems. If you encounter a nice pair of square-base handles at a flea market, it’s sometimes possible to file the old stem down to the new handle dimensions. The best approach, of course, is to take a sample handle with you—metal base and porcelain, if separated—for comparison when shopping.

Most metal handles are screwed on from the top, whether they’re levers, cross handles, or the less common five-point handles. “They’re sometimes called sheriff’s badge handles,” says John. “Though everybody made them—Crane, J.L. Mott, Meyer-Sniffen—they started to disappear in the 1910s.” Fortunately, several manufacturers are offering reproductions today.

A hefty Meyer-Sniffen handle, tarnished but solid nickel.

Speaking of metal, what’s appropriate for finishes? A decade or so ago, polished brass was popular for new period fixtures but, it’s not a typical historic finish because exposed brass darkens quickly, notes John. “Prior to 1920, faucet hardware was protected with nickel plating. When you find an old faucet that is bare brass, that’s what is left after the nickel has worn off.”

Chrome became popular after 1925 because it is a much harder, and therefore more durable finish. Polished nickel was still sold side by side with chrome well into the 1930s, no doubt because of its softer, warmer luster. The beauty of nickel plating, according to John, is that “it stays shiny where you handle it—like the way blue jeans wear to your body.” The appeal of polished nickel, he says, is strong for all kinds of hardware—a big boon for restorers who can now find the finish on almost anything you might want in a bathroom.

Special thanks to the folks at George Taylor Specialties (76 Franklin Street, New York, NY 10013; 212-226-5369).