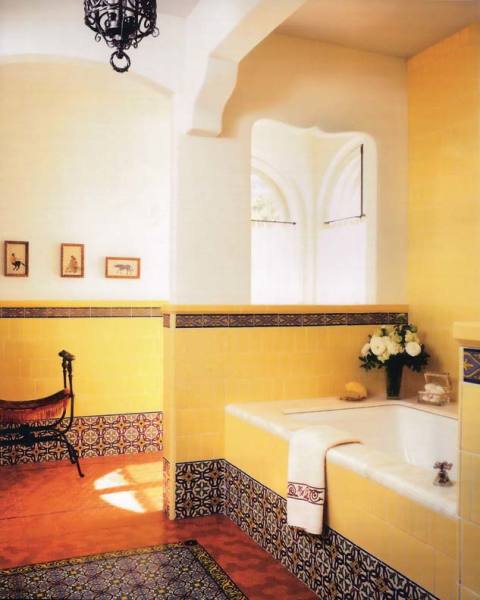

Tiled-in bathtubs, like the marble-topped example in this sunny restored bathroom, evolved to make cleaning easier by eliminating dust bunnies hiding beneath raised clawfoot tubs.

Native Tile

Search the web, and you’re sure to read that America’s first bathtub was installed in 1842—December 20, to be exact. It would be nice if such a mercurial vessel had so neat a beginning—even H.L. Mencken, the newspaperman who concocted this hoax as an uplifting wartime news story, would agree. What is true is that no accessory embodies the metamorphosis of bathing equipment (from moveable furniture to plumbed-in-place fixtures) or helps define the use and look of a bathroom in any era as much as the bathtub.

Antebellum Scrubs

Before indoor plumbing, bathtubs—like chamber pots and washbowls—were moveable accessories: large but relatively light containers that bathers pulled out of storage for temporary use. The typical mid-19th-century bathtub was a product of the tinsmith’s craft, a shell of sheet copper or zinc.

In progressive houses equipped with early water-heating devices, a large bathtub might be site-made of sheet lead and anchored in a coffin-like wooden box.

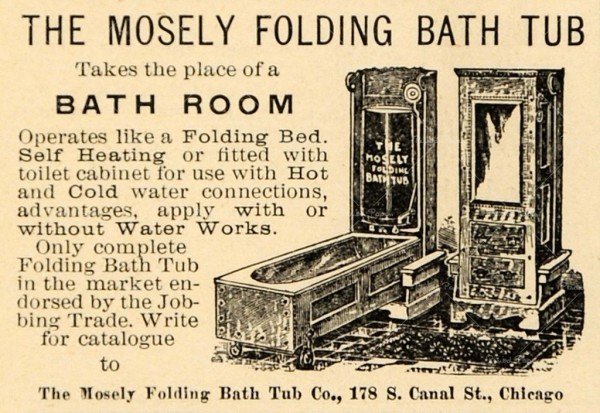

Later, there were ingenious (though ultimately impractical) hideaway alternatives, like the portable canvas tub (similar to a pot-bellied cot), or the Mosely folding bath tub—an armoire-like contraption with a hinged door that pulled down like a Murphy bed to reveal a bathing saucer.

The Mosely Folding Bath Tub pulled down like a Murphy bed.

However, for decades, the bathtub most Americans knew best was the one available in a 1909 hardware catalog: a tinware plunge bath with wood-covered bottom painted in Japan green (a type of pre-1940 enamel paint).

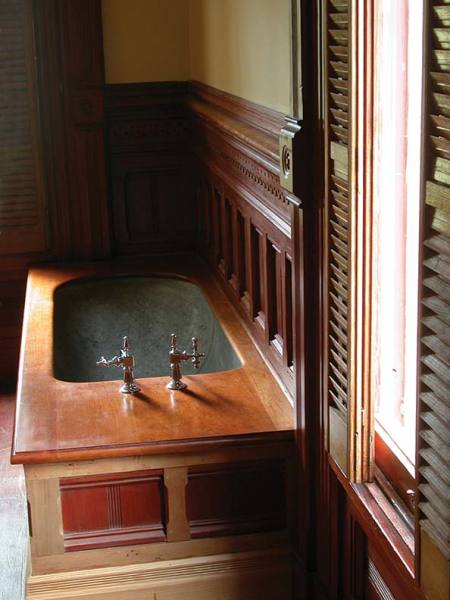

As running water became more common in the latter 19th century, bathtubs became more prevalent and less portable. Though copper was still used for wood-enclosed tubs as late as the 1910s, it more commonly appeared as a liner for steel-cased tubs, rimmed in oak or cherry, that stood on bronzed iron legs.

This wood-encased period galvanized tin tub is in Astoria, Oregon’s 1885 Flavel House museum.

Jerry Boal

Cast iron—the all-purpose material of the Victorian era—had been poured into sinks and lavatories since the late 1850s, and by 1867 the famous J.L. Mott Iron Works was finding a ferrous niche in the bathtub market as well.

However, the big catch with all of these conveniences was corrosion. Copper and zinc discolored readily around water and soap, and the seams of sheet metal were hard to keep clean at all. Iron and steel, of course, rusted eventually, even under the most meticulous coat of paint.

Read more:

- Designing the Victorian Bath for Today

- Master Bath Re-created

- Reproduction Victorian Bathrooms

- Arts & Crafts Revival Bath

Glaze Crusades

A china-like glaze seemed to be the ideal, obvious solution, but producing a vitreous skin on an object the scale of a tub was not so simple. Though cast iron sinks were porcelain enameled, iron bathtubs were a far more complex shape, and when filled with hot water, they could expand more than the coating, risking delamination.

In the 1850s, British artisans cracked the tub-coating code by taking a different tack: all-ceramic tubs with a glazed surface. Because the tubs were both fragile and heavy, they were iffy for export, but the idea found a market on English shores, and by the 1890s, solid porcelain tubs were being fired up by manufacturers like Trenton Potteries.

An ordinary-style tub—sloped at the head, flat and plumbed at the foot—was the most common, and affordable, early porcelain model.

Rejuvenation Archives

The solid porcelain tub scratched many itches. Besides satisfying the need for a seamless, smooth, washable surface that wouldn’t rust, it provided a continuous, roll-over edge around the perimeter of the basin. Indeed, one of the subtle attractions of the porcelain tub was its sensuous, smooth curves and zaftig proportions. Whether it stood on bulbous ceramic legs or muscular sides that ran to the floor (thereby eliminating unsanitary hidden spaces), the porcelain tub was a study in robust modeling. Ads from the 1910s asked, “Why shouldn’t the bathtub be part of the architecture of the house?”

Seemingly the ne plus ultrain bathing, solid porcelain had its downside. For one thing, such tubs were dauntingly heavy and equally pricey. In 1909, prices ran from $180 for a 4 1/2′-long model to $255 for a massive 6 1/2-footer—this at a time when a steel-cased footed tub could be had for around $25. Plus, some bathers felt the pottery mass absorbed too much heat from the water, making it expensive to use.

High-Tech Tubs

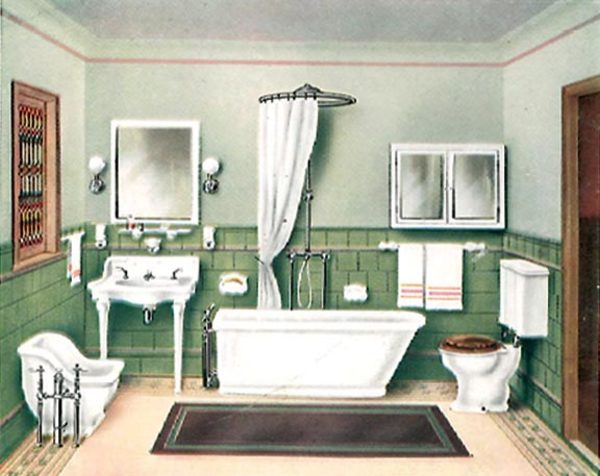

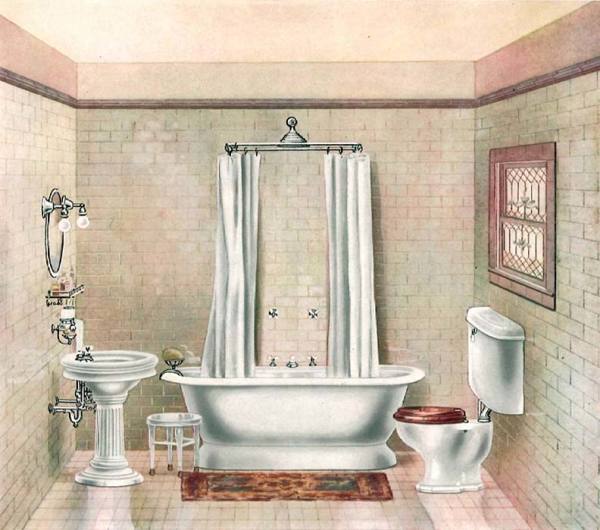

Drawbacks aside, the solid porcelain tub remained the Cadillac of the bath industry into the 1920s and the hallmark of a high-end bathroom. Indeed, before 1910, bathrooms in and of themselves were often status symbols. In an era when houses with running water and waste piping were new and modern, a single bathroom with lavatory, flushing toilet, and fixed tub was a sign of progressive thinking and an essential step in the march toward better hygiene. What’s more, the bathrooms of the wealthy were not so much places of daily cleanup and dressing, but therapeutic laboratories akin to personal spas. The shower we now associate with a daily spritz was frequently a stand-alone cage of multiple sprays designed for skin or kidney stimulation, while tubs were dispersed around the room for soaking one or more parts of the body.

Roman tubs with nearly vertical, sloping round ends were thought to look more balanced and elegant in bathrooms, and usually came with faucets mounted on a long side. (Photo: Rejuvenation Archives)

As multiple-fixture, high-tech bathrooms started to evaporate after World War I (along with the large houses that made them possible), the new paradigm for up-to-date ablution became the porcelain-enameled, cast-iron, footed tub—the ubiquitous clawfoot type still at work for thousands of bathers today.

The Cast-Iron Tub

The J.L. Mott Iron Works was among the first to solve the porcelain-on-iron puzzle in the late 1880s with better techniques for preparing the iron and firing the coating, and when production improvements reduced costs in the 1920s, the cast-iron tub soon took over the bathroom. The typical tub style was the ordinary, a round-bottomed trough with a sloping head and a vertical foot holding water inlets and outlets. The other common style was the Roman, with flat sides and bottom, and identical (nearly vertical) sloping, rounded ends.

Roman Tubs

Roman tubs were thought to look more balanced and attractive in a large room, and were installed with plumbing on one long side. Some manufacturers also offered the rectangular French-style tub with a flat bottom and nearly vertical sides, and one rounded (but not sloping) end. Though the vitreous surface inside was, of necessity, all white, the iron tub sides were often painted in colors or decorated with Greek frets or colored stripes—a widespread fashion prior to 1915. While a boon for bathing the everyman, the footed tub had its drawbacks, too—namely, it was difficult to clean beneath (and behind) the tub shell. Manufacturers bubbled up to this challenge in part by scrapping the cast-iron feet in exchange for a continuous ring base, noting that “they are far superior in sanitation and convenience to the bath on feet.”

The Recess Tub

Another approach was the recess tub, where the cast iron rim was extended into a rectangular, horizontal shelf so the tub could be set flush with the wall (or even a corner or alcove). All that remained then was to tile one or more vertical sides to create a built-in tub that completely enclosed the nefarious undersides and banished all insidious microbes.

Fancy, upscale lavatories could include both a sitz (at left) and foot bath (at right) to complement the bathtub and state-of-the-art ribcage shower, per a 1912 Standard Sanitary catalog.

Rejuvenation Archives

The Built-In Tub

For a new century increasingly on the alert for germs, the only thing better than a tiled-in recess tub was one shipped this way straight from the factory. Casting one-piece tubs with a rim that extended down to the floor in an apron wasn’t easy, but by 1911, the Kohler Company, followed swiftly by its competitors, introduced the built-in tub—still a bathroom standard today. Made with one enclosed side (or one side and an end), the built-in tub was not only efficient in its own right, but as a 5′-long model that spanned the walls of the typical 5′ square bathroom, it became the cornerstone of the modern, functional Jazz Age bathroom trinity: wall-hung lavatory, water closet, and tub-and-shower combo.

Color Craze

Like Henry Ford, who promised auto buyers any color they wanted so long as it was black, sanitary ware manufacturers were at first color-blind to anything but white. White was not only the color of sanitation, making it easy to spot grime and therefore clean, it was also the optimal color to produce reliably from item to item.

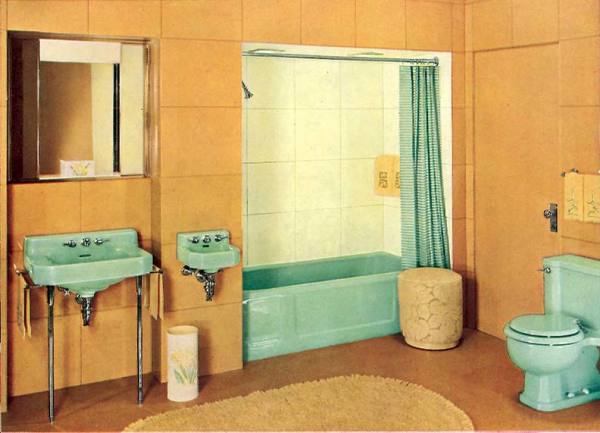

Just like with the auto industry, however, all that began to change in the late 1920s. Once the bathroom reached a plateau as an efficient, hygienic cleansing hospital, it began to be viewed as a vehicle for design and household beauty, and around 1929, color came into the bathroom in a big way.

This inviting bathroom suite, featuring tan vitrolite walls and colorful Spring Green fixtures—including a separate, petite dental sink—appeared in a 1939 Kohler brochure. (Photo: Rejuvenation Archives)

Pigmenting the vitreous finish in fixtures—at first in light pastels, then in deeper hues like royal blue, Ming green, and Chinese red—brought color to the bathroom in solid swaths far more dramatic and permanent than any paint or tile.

“Other rooms of a house can be altered easily with new paint or furnishings,” noted a 1936 catalog, “but the color scheme of a bathroom is always intimately related to that of the fixtures.”

Color also became a nice marketing angle for manufacturers, differentiating one product line from another, as well giving homeowners reason to buy all fixtures from the same source. This strategy became increasingly useful as the housing boom of the Roaring Twenties ran out of gas and crashed into the Great Depression.

Always key bathroom players by dint of their sheer size and function, bathtubs became ever more pivotal when they moved away from white. As color put a design spin on fixtures in the 1930s and ’40s, they began to look—once again—like furniture, with lavatories resembling tables and toilets approximating chairs. In this light, tubs might stand in for beds, especially when detailed with the rectangular outlines popular in the Art Moderne era and in velvety colors of rich maroon or black. It was a long way from the tin tub that had been hauled out of a closet only a generation or two before.