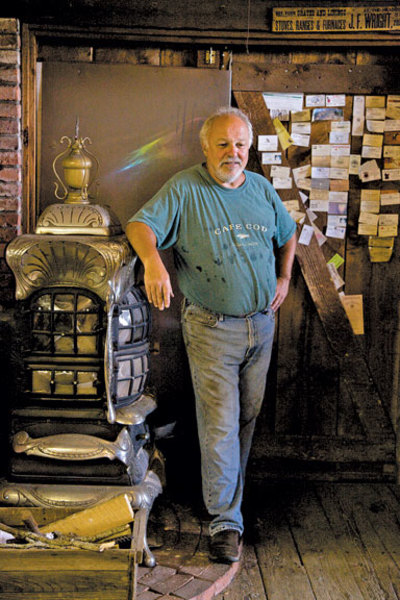

Doug Pacheco restores antique stoves in an old horse barn in Massachusetts.

The Barnstable Stove Shop is not unlike many of the varied one-owner businesses dotting the byways of rural Massachusetts: As you pass the old coal depot, turn left just after the tracks of the Cape Cod railway; if you pass the town cemetery, you’ve gone too far. There is a universal familiarity to pulling down the tree-lined drive that leads up to the massive 1880s barn where owner Doug Pacheco plies the wares of a homegrown establishment achieved after decades of commitment, earned one day at a time. And in Doug’s case, measured one stove at a time.

It becomes quickly evident why locals refer to Doug as the “stove guy”—and not because of the huge gold-leaf “STOVES” sign hanging above the barn’s large sliding door. He has hundreds of antique wood-, coal-, and gas-burning stoves at various stages of disassembly interspersed throughout the swaying long grass of his front yard. Like rusting steel tombstones from a forgotten era, they compete for space with the crowded footpaths that converge toward the office entrance, forcing determined visitors to just “go around.”

“We call it the boneyard,” Doug says with a shrug. “Believe it or not, we took three stoves out of there—two Glenwoods and a nice cookstove—and redid them for the National Park Service out in Provincetown—all part of an effort to restore the old Life Saving Station.” At first glance, wayfaring tire-kickers might have difficulty with Doug’s claim. And apparently the people on the committee tasked with selecting the antique stoves were guilty of the same disbelief. “I told them the stoves were perfect, that everything was there—they came out of an old dairy barn in Whitman, Massachusetts. In one month, we restored them with high-back shelves, authentic coal grates, new kerosene burners—drove them up there and installed them. They still can’t believe it was the same three stoves!” he exclaims.

Despite first inclinations, Doug’s unbridled enthusiasm comes from a different place. No doubt, as sole proprietor he has done his share of buying and selling, researching and marketing—all required at various times in various amounts to help build a successful business. But deep down, beneath the showmanship, shines forth a light of peaceful joy, belied by his unwavering belief in the goodness of rediscovering the boundless history wrapped up in countless piles of discarded cast iron, sheet metal, brass figurines, and nickel-plated trim. “Every stove has a different story, and if stoves could talk, they’d have a lot to say,” he says, calmly resonating with the rarified wisdom of late baseball great Yogi Berra.

In the Beginning

Pacheco begins the restoration process by disassembling the old stoves.

Inside the main entrance of the restored horse and hay barn, there’s a plethora of paraphernalia to support Doug’s convictions. Behind the dozen or so pristine restored heat stoves that adorn the showroom floor space—like proud jewels in a king’s crown—one is bombarded by the countless number of artifacts, procured over time, that take up every square inch of wall space. They document the rise and fall of the cast-iron stove industry from its modest conception of “portable fireplaces” in the early 1830s, through its meteoric rise with mass production during the post–Civil War industrial revolution, to its eventual demise with the enamel gas-burning units of the 1920s.

There are hundreds of photographs of the factories where the stoves were made, of the showrooms where they were sold, and of the churches and saloons where they were used—everywhere from Connecticut to Colorado, Maine to Florida. Adorning the walls and support beams are the boldly colored marquee signs once used by dealers to grab one’s attention in favor of a particular brand, with names like Acorn and Atlantic, Splendid and Summit, Red Shore and Red Cross, Harold and Modell, Plymouth and Waverly.

Many of these companies were concentrated in New England. Both Boston and Taunton were once known as “stove cities,” with Crawfords and the broadly popular Glenwoods being produced in each town, respectively. “The old Crawford factory was actually located along the Charles River in Watertown,” explains Doug.

Other factories weren’t as fortunate. As demand for stoves began to shrink after the Great Depression, foundries closed and workers dispersed, creating ghost towns out of previously thriving communities. Ironically, one of the only major companies to endure the transformation was Garland Stoves of Detroit, Michigan, which still makes commercial-grade gas ranges today.

“The absolute mecca of stove building was the Troy and Albany area of New York,” says Doug. “They had unlimited access to water energy from the Hudson River, and huge deposits of some of the finest sand required to make the hand-cut casting molds.” Raw iron ore mined in northern Michigan had a short trip through the Great Lakes down east through Buffalo and then over to the booming factories around Troy and Albany. “Many of the early artisanal column stoves from this area are considered by many collectors as the most beautiful,” says Doug.

Pacheco then torches and sands the stoves, and adds a coat of paint to bring them back to life. The nickel plating is done in New Bedford.

Works in Progress

Sliding through a door at the back of the showroom, we enter into the smaller workshop, where Doug begins the actual process of breaking down stoves. It’s a space diametrically opposed to the quaint, museum-like organization witnessed in the room before: bright lights overhead reveal a burnt black residue covering the entire space, developed over years of torching, welding, sanding, and painting. Hundreds of metal hand tools fight for shelf space with canned aerosol solvents—all surrounding a cement, board-layered workbench—while strips and shards of scrap metal are scattered across the floor.

Once disassembled, the pieces are wheelbarrowed out the screened side door and down a ramp to the sandblasting pit, where each load gets a “good going over” to remove the dirt and corrosive rust accumulated from a century of neglect. After blasting is complete, all of the pieces are immediately returned to the shop—or just outside if the weather’s nice—for painting and reassembly. “We try to do everything as it was, as it should be,” says Doug. Not an easy task when there are thousands and thousands of parts pertaining to each stove’s specific year, make, and model—mostly lost in attics, cellars, garages, or storage sheds across America.

Back through the workshop, we cross over to the other half of the barn’s floor space: interior storage for roughly another 200 stoves. “I’ve taken inventory a couple times,” sighs Doug, “but I’m losing track these days.” Quietly standing in neatly organized rows, the stoves seem more intact and in better overall shape than the boneyard’s less-organized piles of rusty specimens—partly due to being out of the weather, but also because they came to Doug in more complete packages. “This is what we call our ‘undone inventory,’ stoves that have all the parts and just need to be put together. We reseal, reline, repaint, reassemble, re-everything. Make the stove brand-new, just like you see ’em back in the showroom!” His energy is infective, while his straightforwardness bears a light burden. “Do you want to go see the museum?” he asks.

If These Stoves Could Talk

The showroom of Barnstable Stoves is reminiscent of a museum, with stove paraphernalia lining the walls.

Directly across the road from Doug’s barn is a small and tired farmhouse, only steps from the paved road. Plate glass windows across the front reflect the traffic whizzing by, yet also reveal another stash of wonderfully preserved antique stoves—all standing at attention while peering out at a world that keeps passing by without realizing what treasures await inside. “This used to be an old general store and post office,” explains Doug. “I put a roof on it and gave it a coat of paint when I first moved in—it was really a cool spot back then,” he explains. “It could really use some more work today.” The owners—two old ladies in the bigger farmhouse next door—have rented the space to Doug since 1978, and so far haven’t mentioned changing the lease. “I’d like to set it up as a museum when I retire,” he confides.

Just as in the barn across the street, Doug has been able to squirrel away maybe another 150 antique stoves, so many that the spillover was repopulating a “Boneyard, Part Two” out in the tall grass behind the house. “We call that the Out Back!” Doug laughs and then turns semi-serious. “I’m trying my best to keep it to a minimum.”

Moving through the structure, one can’t help but notice that each room contains a different style of stove that pertains to a different period: The entryway holds 10 to 15 early column stoves of the 1830s; the front parlor another 10 basic cookstoves with finer details from the 1840s; the hallway harbors 10 more basic models from around the Civil War; a room further back in the house contains 10 to 15 taller, more slender “oak” stoves from the 1880s that were used in front parlors and burn either wood or coal; the next room back holds a few beautiful turn-of-the-century six-lid cookstoves that circulated hot water to heat more efficiently; and the last room retains a smattering of miscellaneous units, predominated by some gas-fired enamel stoves from the 1920s.

As we move from room to room, Doug explains some of their specific history, as if already preparing for an eventual role as curator. “This one here was a ‘column stove’ from the 1840s, with either two to four exposed columns connecting the stove to a heat box higher up the flue to help disseminate more heat before exiting the chimney. The four-column was considered the crème de la crème for its time.” He continues: “Look at this rare cookstove from 1855 made in Albany. It’s the size of a table with four large cook lids—very solid! It had a cast-iron liner to protect the fire wall of the box from the tremendous amount of heat.” Redirecting again: “That one was called ‘The Harvard’ and was made by Fuller and Warren, one of the bigger companies in the Troy/Albany area. Built around 1875, it was a very popular coal- or wood-burning Franklin-type stove with a ‘fire view,’ which sells pretty well to people even today.”

The history lesson is peppered with occasional background information of a personal nature, as if the stoves were lost relatives at some family reunion he hadn’t seen or heard from in ages. “Here’s one still wrapped in 1930s newspapers from when I removed it from the Empire Stove Company’s warehouse attic!” Coming across a modern boxed unit, he recalls, “Just restored a gray one of these old Fairmounts—wood-and-gas combination—for a woman over in Wareham who inherited it from her father. It was all busted up inside, and we totally went through the whole thing: new grates, new lining, new gas fittings, new everything. Brought it back within a month!” Pointing to a nice oak stove, he says, “This one came from Florida—Tampa Bay area. Traveled down with some scientist from New York who was a butterfly expert. Wound up at his other home in Sarasota.”

One can’t help but wonder how he keeps all the names, dates, styles, places, and people cataloged. “It’s all right here in the Library of Congress,” he says, pointing to his head. “Good thing I still have my marbles as best I do,” he deadpans in his best Boston accent, somewhat lost from living around the cranberry bogs of Cape Cod for almost 40 years. “Seriously, most every stove can tell you what you need to know: what model it was, where it was made, who made it, and what year they made it—all stamped into the design when forged. On top of that, companies were forced to come up with new designs to coincide with the expiration of their patents, which occurred every 10 years or so. After a while you recognize what parts go with what pieces.”

End of the Line

After locking up the “museum” and dodging traffic, Doug explains the high point of his annual calendar: “Gotta pack up for the Brimfield Antiques Fair this week.” There, he’ll hold court with hundreds of serious antiques dealers, all competing for the attention of thousands of potential customers. “After that, it’s up to Maine for the annual stove collectors’ conference,” which should be well-attended, as one of the sponsors is liquidating his entire collection at auction. “Then, it’s back to Barnstable—back to the trenches, as I call it.” We’re briefly interrupted by the Cape Cod Central Railroad’s scenic train, passing parallel to Doug’s driveway less than 100 feet away, completely restored to its original condition. The train disappears and Doug continues, once again plumbing the depths of Yogi Berra’s book of wisdom: “If I don’t do it, then it doesn’t get done.”

Back inside the barn, I ask Doug how long he intends to keep up the current pace. “As long as I can,” he replies. “I’m hitting 60 in August—I try to stay in shape and keep at it. Got another 10 years or so before I can get things in line maybe the way I’d like to.” Despite 30-plus years in the stove restoration business, Doug says, “Basically, business is one day at a time and one stove at a time. You have to sell to buy, and you have to buy to sell—it’s a vicious cycle, but you have to just keep the wheels turning.”

With that, we say our goodbyes, and on the way out the door, a worn bumper sticker placed near the clear glass sidelight catches my attention: “Happiness is a warm wood stove.” I start thinking that maybe before this winter starts, I’ll pay Doug Pacheco another visit, but this time as an interested buyer.