Unfortunately, we’ve all seen them—restored bathrooms that almost got the details right. Often they boast spot-on period fixtures, faucets, lights, and medicine cabinets, but are accompanied by a floor that looks as though it belongs in a 1950s science fiction movie—or worse yet, in the summer palace of an Italian baron.

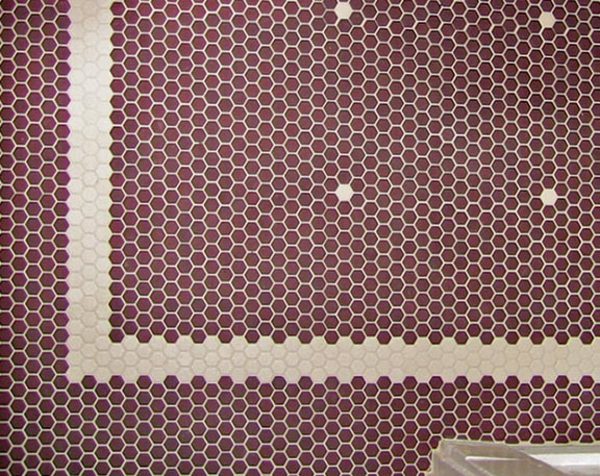

The restored bathroom in an 1894 house boasts a complex mosaic floor that resembles a richly detailed rug.

Bo Sullivan

Don’t let flooring selections derail your restoration project. Take a page from history’s rich offerings of tile designs to find a perfect, and appropriate, match-up for your bathroom, no matter how understated or complex your home’s architecture.

Tracing Tile

Ceramic tiles have existed for thousands of years—in fact, archaeologists have unearthed numerous mosaic floors beneath the ashes at Pompeii. But owing to production methods that were lost or forgotten over time, ceramic floor tiles didn’t become prevalent in the United States until the Victorian era.

Their popularity began in England, thanks to the Gothic Revival movement, which reintroduced medieval encaustic tiles—individual tiles bearing an inlaid pattern in a contrasting color, created by the new dust-pressed method—to a receptive public. As with many home fashions dating to this time, the tiles were brought to an American audience largely through Andrew Jackson Downing’s 1850 book The Architecture of Country Houses.

An installation of geometric tiles in a restored Victorian-era bath.

Courtesy of Tile Source

Downing recommended entry floors tiled in marble or pottery for their durability, moderate cost, and “good effect.” His book makes direct reference to encaustic tiles—which at the time would have come from England in a range of browns inlaid with blue and beige tones (and would have been expensive imports reserved for the wealthiest homeowners); examples of such early installations can still be seen on the front stoops of many upscale high Victorian homes in California. (Another tile of the era, geometric, created intricate patterns from solid individual tiles laid in contrasting colors and shapes.)

America’s tile selections would soon expand, largely thanks to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The Philadelphia Exposition featured many exhibits of sanitary ware and decorative European floor tiles—including displays of encaustics by Herbert Minton, one of the architects of the Gothic Revival—and the buzz around them convinced their manufacturers there was a marketplace for such products in the U.S.

The companies soon established satellite offices, and their presence spurred on a domestic tile industry. The Pittsburgh Encaustic Tile Company is considered the first successful American company to manufacture ceramic tile commercially in the U.S., beginning in 1876, and by 1894 dozens of companies had joined the fray. Their early offerings dovetailed nicely with late Victorian-era discoveries on germ theory that would propel a desire for ultra-sanitary surfaces in kitchens and bathrooms, which made tile an ideal flooring medium.

Early mosaic floors could be all white or feature a subtle, random pattern of dots or flowers.

Photo: Jason King

Mosaic Floor Tile Patterns

In this fresh, germ-sensitive frontier, all-white tiles became preferred for bathroom floors because they were considered the best for spotting—and thus eliminating—dirt and microbes, and keeping a home’s inhabitants healthy. It didn’t take long, however, for improvements in the world of tile—new machinery that made manufacturing faster and easier, plus innovations in the tile-setting process—to usher in more creative decorative installations.

Pre-mounted sheets of 1″ ceramic mosaic tiles (in a range of geometric shapes like honeycomb, pennyround, and square) made intricate designs less time-consuming to achieve. For example, by replacing a few individual mosaics with tiles in a contrasting color, a basic pre-sheeted white 1″ hex tile floor could readily be accented with rosette flowers or a simple solid border.

Since these uncomplicated designs were relatively easy to create, they became as common as all-white sanitary bathrooms in houses of every architectural style beginning around 1900, shortly after bathrooms started appearing in private homes. Soon, though, homeowners who could afford the extra cost—typically those with more architecturally elaborate buildings—were selecting mosaic floors in more intricate designs. Such patterns could include a field of graduated geometric shapes—like diamonds, pinwheels, and nautilus shells—that were decorated with flowers, starbursts, and more. To add even more interest, these decorative fields were surrounded by a solid framework of border tiles bearing yet another pattern—Greek keys, for example, or intricate vines and leaves, or layers of solid borders reminiscent of an area rug. Thus the finished floor became, in essence, a rich, multi-layered tapestry of mosaic tiles.

A mosaic floor uses a simple order to frame a field highlighted with dots.

Courtesy of Northwest Classic Homes

The evolution of such nuanced, intricate designs can be traced to England’s Gothic Revival tile creations. Peruse late 19th- and early 20th-century tile catalogs side-by-side, and you’ll see many similarities between encaustic and geometric tile installations and the mosaic ones that followed.

“Encaustic tiles were often used as featured centerpieces within a matrix of colored geometrics,” says Riley Doty of the Tile Heritage Foundation. “Color patterns were frequently highlighted by complex transitions between the use of a diagonal orientation and that of a square grid. A distinct tile border usually framed the ensemble.”

Practical Applications

Finding the right mosaic floor tile patterns to suit your bath depends largely upon your home’s architecture. If your house is classic and clean-lined (say, Arts & Crafts or Colonial Revival), you can’t go wrong with a basic hex mosaic interspersed with dots or small flowers, and framed by a simple border. Such tiles are a good choice for all houses, actually, because they were in vogue shortly after the earliest bathrooms arrived indoors.

A modern floor’s geometric tile-inspired installation of contrastic mosaics.

Courtesy of Kohler

If your home is a high Victorian, geometric or encaustic tiles (or a combination of the two) also could work. While they wouldn’t have appeared in many original bathrooms, their popularity during the Victorian era, and their roots in medieval England, make them an interesting historically based choice for homeowners seeking creative flooring options. They also could suit homes in English-derived architectural styles, from Gothic Revival to Tudor.

As with all house projects, look to your building’s history for clues. The grander the home, the easier it can carry off a more elaborate design. Whatever tile and pattern you ultimately choose, rest assured that if it’s rooted in history, it will suit your house better than any of those contemporary offerings that look promising in the store, but are a letdown after installation.