Like many buildings dating to around 1900, the house mixes elements from several architectural styles, blending a Foursquare form, Colonial Revival entry, and Shingle treatment in windows and bays.

There’s only one explanation for how my husband, Rick, and I bought a 110-year-old Colonial Revival-style house with shag carpeting, pink stucco bedrooms, and a sagging porch: We watch too much TV. On a show, a home renovation typically takes eight episodes, which I translated into about three months. That timeframe seemed so manageable, Rick and I figured we could handle the project, even do most of the work ourselves.

“I think we should buy it,” Rick whispered when we first saw the house’s 10′-high cove ceilings, stained glass windows, and open floor plan. “Me, too,” I whispered back. Not that Rick and I were completely naive. We were prepared to later discover noxious, expensive problems: a leaky oil tank, perhaps, or asbestos in the industrial-looking ceiling tiles. What we didn’t expect was that our lucky finds would be the ones to upend our budget, our timetable, and our relationship.

Tools of the Trade

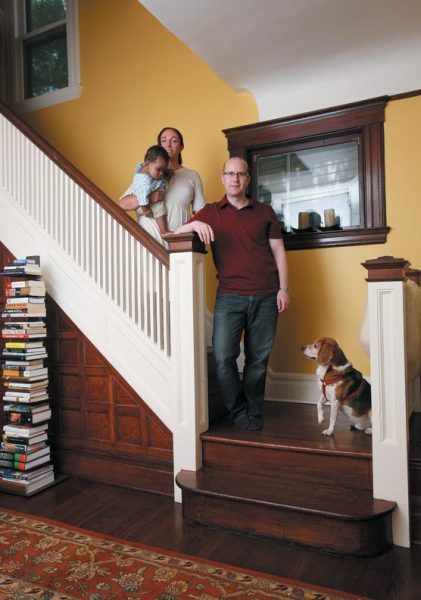

Christina with husband Rick, baby Jack, and the family beagle on the stairs of their 1890s house in New Jersey.

I blame it all on the wainscoting. When we pried away sheets of photo-finished, 1970s paneling, underneath we found wainscoting made of real quarter-sawn white oak, painted white but otherwise intact. One little unpainted spot behind the living room radiator was the first tangible evidence that our house was once tasteful and well maintained. “It’s a shame to leave that wood covered with paint,” I thought. “I’ll strip it; how long could it take?”

After experimenting with various goops and pastes, I hit one that worked well, and soon I was readily peeling away long, satisfying sheets of paint from flat areas of the wainscot. Curves and moldings proved trickier, however, so I began attacking these spots with increasingly smaller scrapers. I waged war on the paint this way for a couple of weeks, until I decided I needed even tinier instruments to get into the crevices. That’s when I discovered I could buy a set of used dental tools on eBay for less than $10. Armed with these miniscule tools, I started to scrape paint away from the curves, cracks and moldings of our living and dining room wainscot, a job that makes cleaning a bathroom with a toothbrush look easy. Over the next few months I spent so much time with these little scrapers that I gave them names: Captain Hook, Baby Hook, and Twirly Whirl.

The spot that inspired it all: Original, unpainted wood in a dark stain where the radiator once stood is visible in the living room amid a sea of white wainscoting. (Photo: Christina Kozma)

Paint stripping became my hobby, a calling, and an obsession. Soon I began studying the stripped woodwork in public places (lots of it done pretty badly, I’d say) and reading up on it in my spare time. I even found a New York Times article about a 70-year-old woman who spent decades peeling every bit of paint off the woodwork in her Brooklyn brownstone. Once she finished, she missed the challenge so much she looked for another house on which to work. That article brought me back from the brink—sort of. “I will not become her,” I vowed, but I have to admit there’s a Zen-like attitude that comes with paint stripping. At first, the paint peels off in one big strip from the flat surfaces, then tools gradually work out the rest. It’s a slow, meticulous process that leads to meditation. I even came up with a mantra. “Progress is progress,” I repeated under my breath, as I moved painstakingly through the rooms, panel by panel.

When you’re working on a house while living in its pink stucco attic (after evicting the dead squirrels), and shaking your suits free of plaster dust each Monday before going to work, I guess it’s inevitable that tempers will flare. I was so tired I looked forward to the work week so I could sit still for a few hours. After a while Rick got a little sick of hearing about Captain Hook and mantras and the paint colors our house had once been (white, mustard-gold, mint-green, and blue). During the 18 months I spent stripping woodwork, he repainted the porch, updated the electrical system, renovated a bathroom, chipped away the faux brickwork in the den and built a new fireplace mantel. As Rick crossed one project after another off the list, he grew frustrated with my slow pace. “You’re the one who wanted to redo dining room,” I reminded him. “We’d be done by now if I wasn’t stuck stripping paint.” Then we exchanged a few more words—“You’re mean and impatient” and “I can’t take this anymore!” are the ones I remember—and I threw a tangerine at him.

In the living room, Christina and Jack play beside the fireplace mantel Rick rebuilt, one of many projects he completed as Christina removed paint.

Avoiding an Emotional Mushroom Factor

As we watched our dog eat the tangerine and vomit it back up, we realized that it wasn’t a good idea to continue the way things were going. “I can’t stand how crabby you always are,” I said, simulating crab pincers with my thumbs and waving them in his face. “You’re right,” Rick replied with a small smile. “We can’t keep fighting like this all the time. We’re on the same team here. Let’s be on each other’s side.” From then on, whenever one of us got a little testy, we’d look each other in the eye and say sincerely, “Honey, I’m on your side.” Usually it worked.

The author uses a two-step stripping process—brush on stripper, then overlay a waxy paper—to lift away decades-old glossy white paint. (Photo: Christina Kozma)

We also came up with what we called “together weekends,” times when we would both work on the same project rather than splitting up the tasks. In this way I learned all kinds of things: how to cut and tape drywall, why 2x4s don’t measure 2″ by 4″, how to use a band saw. Rick learned to strip paint, although he never grew to love it the way I did. (Actually, his reaction was, “This kind of work is why they invented the word toil.”) Nonetheless, he did develop an interesting stripping technique involving brute force and steel wool.

Then we discovered a lucky windfall. We had devoted so much time to working on the house that we had no time to spend money on clothing, vacations, or eating out. That savings, combined with a larger-than-expected tax refund (thanks to deducting mortgage interest and property taxes for the first time), left our bank account a little plumper than we expected, so we explored a novel idea: hiring contractors to finish the job.

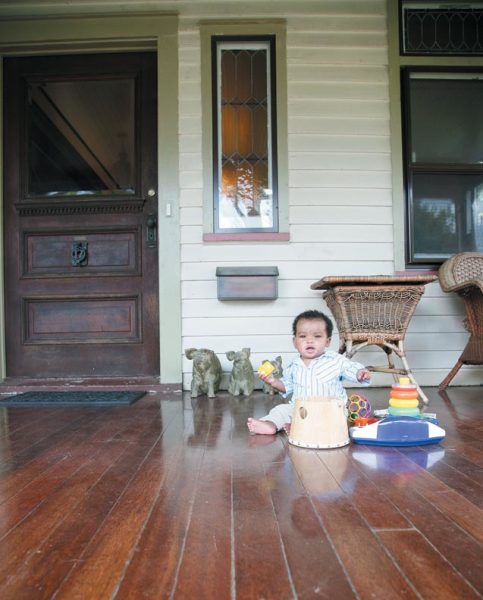

Jack entertains himself on the mahogany porch floor, a project the couple farmed out to contractors after stripping the front door themselves.

Unfortunately, we could only put this concept into practice a few times before the money ran out, but we did manage to have the exterior painted, the wainscoting stained, and the floors refinished. The house looks pretty good now, but more important, we live like regular people, with time on weekends for bike rides, watching movies, and having friends over for dinner.

Of course, having dinner guests is a challenge given our as yet untouched appliances—a broken stove and a refrigerator that doesn’t close properly. That’s why we have plans to renovate the kitchen, starting this year, but what Rick doesn’t know yet is that there’s one wall of painted, exposed brick that I’m just dying to strip.