The garden at Dumbarton Oaks is renowned for its blend of naturalism and formal elements, such as this view from the terrace overloooking Crabapple Hill. (Photo: Dumbarton Oaks)

The Arts & Crafts movement left behind more than just the houses and decorative objects for which it is famous—it also bequeathed a rich legacy of gardens. While certain features (pergolas, arbors, beautiful flower borders) may come to mind when thinking of an Arts & Crafts garden, by and large, they elude definition. That’s because there are no hard and fast rules: Arts & Crafts gardens are an approach to design rather than a style. But what they lack in common shape, size, or location, these gardens make up for in individuality, regionalism, craftsmanship, and, most important, a harmonious relationship with the house.

As Arts & Crafts simplicity replaced complexity, and handmade items replaced machine-made, smaller country houses took the place of the vast Victorian estates that were typical of the mid-19th century. In Great Britain, where the movement began, these new houses were inspired by examples from earlier times. Scottish homes by leading Arts & Crafts architects Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Robert Lorimer were entirely different in character from those by their English contemporaries Edwin Lutyens and Baillie Scott. The one thing they shared, however, was a reverence for local building traditions and materials.

At Red House, William Morris’s first home and garden, the showy patterned plantings typical of Victorian gardens are eschewed in favor of ornamental fruit trees and climbing roses. (Photo: Judith B. Tankard)

The same considerations applied to the gardens adjoining these homes. Gardens took on a new meaning as an essential component of the house, rather than as a separate entity. William Morris sparked the underlying philosophy for garden design of the Arts & Crafts era. Although he certainly wasn’t a garden designer, his own garden reflected his home’s unique personality. At Red House, his first home, built by Philip Webb in 1859, Morris created a medieval-inspired pleasure garden, filled with old fruit trees, climbing roses, and simple flower beds. This concept was a far cry from typical Victorian gardens overflowing with exotic foliage and vividly colored, pattern-planted annuals, ideas that Morris loathed. At Kelmscott, the ancient manor house near Oxford where he had some of his workshops, Morris created a romantic garden in the farmyard enclosure, surrounded by low stone walls and an ancient stone dovecote, and grew borders of hardy plants and herbs for his dyestuffs. Morris’s love of English flowers provided inspiration for his firm’s famous wallpapers, textiles, and tapestries rendered in delicate, harmonious colors.

Beyond Morris, one of the most influential Arts & Crafts gardens in England is Gertrude Jekyll’s—no one did more to enlighten people about appropriate gardens for the Arts & Crafts houses that were being built in the early 1900s. Jekyll’s books extolling the finer points of horticulture and design are still excellent resources for gardeners today. Her gardens at Munstead Wood, which represent the perfect expression of the symbiotic nature of house and garden, evolved over time rather than following a strict plan. Here, she designed a series of “garden rooms” that led from one area to another, each one with a distinct personality and providing a vista to the house. Most of these areas were for specific seasons—an April bulb garden, a June cottage garden, an autumn aster garden—but her greatest innovation was her artistic approach to combining plants for both color and texture.

The garden at Hestercombe, which Gertrude Jekyll designed with architect Edwin Lutyens, is divided by water rills bordered with local stone. (Photo: Andrew Larson/Hestercombe)

Munstead Wood served as a prototype for gardens she designed in collaboration with Edwin Lutyens, one of the most famous of which is Hestercombe, which was built with local stone from Somerset to give it a rustic quality. A long pergola framing a view over the valley encloses the garden on one side, with high stone walls on the other two. Jekyll draped the pergola with a variety of climbing roses and vines, while fragrant plants such as lavender bordered the stone path underneath. Delicately grouped plants and water features edged with paving accentuate the garden’s geometry.

Naturalistic (or wild) gardens also enjoyed a heyday during the Arts & Crafts period. William Robinson, the prophet of wild gardening, was among the earliest to advocate the cultivation of hardy plants rather than bedding plants. His books, The Wild Garden and The English Flower Garden, influenced generations of home and professional gardeners alike, including Gertrude Jekyll. Gravetye Manor, his home in England (now a luxury hotel), was a proving ground for thousands of his favorite flowers, including hundreds of varieties of carnations, clematis, and roses. Vine-covered pergolas and arbors enclosed the formal gardens near the house, and thousands of bulbs and wildflowers bloomed in the surrounding meadows and woods. Robinson’s incorporation of both formal and informal areas was one of the lasting legacies of the Arts & Crafts garden.

Coming to America

In America, the Arts & Crafts movement reflected the country’s melting pot of nationalities and its diverse geography. While it was mostly confined to the upper classes in Britain, the movement gained widespread appeal with the vast American middle class. Gustav Stickley influenced legions of American homeowners, and his advice often tallied with that of his British colleagues. “Let garden and house float together in one harmonious whole,” he advised in the pages of The Craftsman. He recommended the pergola as an ideal connection between house and the outdoors and especially useful for screening in tight suburban areas.

In a small private garden in Hampshire, Gertrude Jekyll created a wildflower border that embraces the theory of naturalism in Arts & Crafts garden design. (Photo: Judith B. Tankard)

Regional variations in American garden design take into account climate and cultural traditions. Along the East Coast, where the Colonial Revival dominated, romantic, old-fashioned flower gardens were especially popular. The Prairie School aesthetic prevailed in the Midwest, with the use of native plants in organic settings. Naturalistic gardens and informal materials also reigned in California, where outdoor living prevailed and the bungalow reigned as the ideal Arts & Crafts home. The Pacific Northwest, which is known for its wide variety of plants, segued into Japanese influence.

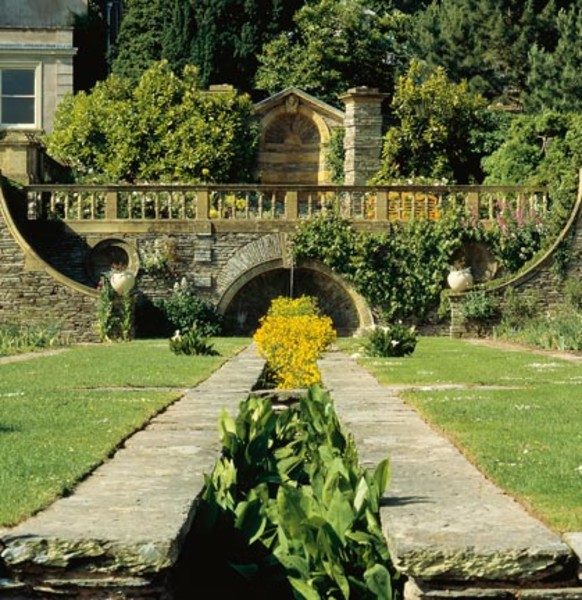

The emergence of the new profession of landscape architecture in America around 1900 also made a significant impact on garden design. In their individual ways, landscape architects incorporated Arts & Crafts elements and concepts, such as the intimacy of house and garden. At Dumbarton Oaks, a majestic garden in Washington, D.C., Beatrix Farrand skillfully combined both formal and naturalistic elements in a series of garden rooms near the house and sweeping Robinsonian-inspired wild gardens on the hilly perimeter of the estate. Ellen Shipman, who specialized in formal gardens for modestly sized homes, was an expert at linking house and garden together with a simple plan and effusive shrub and flower borders. She embellished her gardens with benches, small structures, and garden ornaments.

A diamond-patterned stone path leading from the home is the focal point of a Yorkshire garden. (Photo: Judith B. Tankard)

Creating an Arts & Crafts Garden

While the Arts & Crafts movement itself was short-lived, its influence on home and garden design has been long-lasting. There’s scarcely a garden in Britain or America that doesn’t owe something to the movement’s ideals. While the scale of most Arts & Crafts gardens is too big for contemporary homeowners, the basic concepts and detailing can be adapted easily to small properties. To make a garden following the movement’s principles, start by creating one that is appropriate for the style and size of the individual house. The scale and complexity of the garden should echo the house, and the choice of plants should be informed by sensitivity to color and texture. A judicious amount of well-placed ornamentation should complement rather than overshadow the garden. A garden that works for one house shouldn’t be uprooted to another area of the country—or even across the street. It is better to draw inspiration from other gardens and reinterpret it for your own conditions. It all boils down to making the best use of your site, linking the garden to the house, respecting regional traditions, and using local materials.

Depending on the area of the country, one of the best ways to begin a new garden is to create an enclosure with stone walls, dense hedging, nicely detailed trelliswork, a vine-covered pergola, or whatever works for the individual setting. The site also should dictate the selection of plants. Rocky outcrops in Maine call for a naturalistic treatment, whereas a Midwestern garden should acknowledge the region’s wealth of prairie plants. In California, choose plants that thrive in a year-round Mediterranean climate, whereas the Pacific Northwest is perfect for a rich palette of evergreens. Plantings should be selected with care so they harmonize with the house. To complete the look, consider a paved path, low shrub borders, a long arbor, or an ornamental feature placed on axis with the house to create a definite sense of connection between house and garden. Planters also provide a great effect in small gardens.

In the end, it matters less what the individual plants and elements are, as long as they provide a visual connection with the house, and the garden as a whole is sympathetic with the surrounding environment.

Judith B. Tankard is a garden historian and teaches at the Landscape Institute of Harvard University. She is a preservation consultant and has written a number of books and articles about landscape history.

Web exclusives: See our suggestions for decor and plant species for your Arts & Crafts garden.