Perhaps your treasured hot-water or steam system suffered a catastrophic freeze, or the forced-air HVAC system is reaching the end of its useful life. Or maybe heating and cooling bills in that rambling old pile you call home are cutting into retirement savings. If any of these circumstances sound familiar, your home may be a candidate for a geothermal HVAC system—even if the house is on a compact lot in a historic streetcar suburb.

Geothermal systems make use of the free, renewable energy stored in the earth. A geothermal heat pump uses the constant temperature underground as the exchange medium for heating and cooling, instead of outside air. Just a few feet below the surface, ground temperatures are significantly warmer than the air above during winter, and much cooler in summer, usually averaging around 50° F year round. For this reason, a geothermal heat pump uses less energy to warm indoor air when it’s cold, and to cool the air when it’s hot outside—all without directly burning any fossil fuel.

As part of a vertical-loop geothermal installation, a drilling rig prepares to bore deep holes in the front yard of a Queen Anne house in a historic Syracuse neighborhood.

Courtesy Natural Systems Engineering

While the upfront costs of geothermal are about twice that of conventional systems, the energy savings are so significant that most homeowners will recoup their costs in five to 10 years—sooner, factoring in the state and federal tax incentives now available. (Several of the larger geothermal companies also offer financing on favorable terms.) The whisper-quiet systems make a lot of sense for older houses with generous floor plans and minimal insulation, too.

The key component of any geothermal system is the ground loop system. Composed of high-density polyethylene pipes that contain a water–ethanol mix to prevent freezing, the loop system is buried below the freeze line. During cold weather, the temperature-sensitive fluid circulates and picks up heat from the steady temperatures underground and delivers it to the house. The heat pump concentrates the thermal energy and transfers it to conventional ductwork or an under-floor radiant system, which circulates the heat. In warm months, the process is reversed and the cooler fluid exhausts heat out of the house. As a bonus, the unit can assist with hot-water heating.

There are several types of ground loop systems, and all require quite a bit of earth moving and lawn repair. The most common and cost-effective is the horizontal loop system. Piping is laid in trenches from 100′ to 400′ in length. Installing the trenches requires enough land, of course—at least .25 of an acre, and often up to .75 acre. In a variation called the “Slinky,” looping the pipe in overlapping circles allows the use of more pipe in a shorter trench, cutting down on installation costs and permitting horizontal installation on smaller sites.

Vertical loop systems are used in locations where there isn’t enough land to lay a horizontal system, like small lots in historic neighborhoods. In a vertical system, holes are bored with a drilling rig, and a pair of pipes with special U-bend fittings inserted into the holes. A typical home requires three to five bores with about a 15′ separation between the holes.

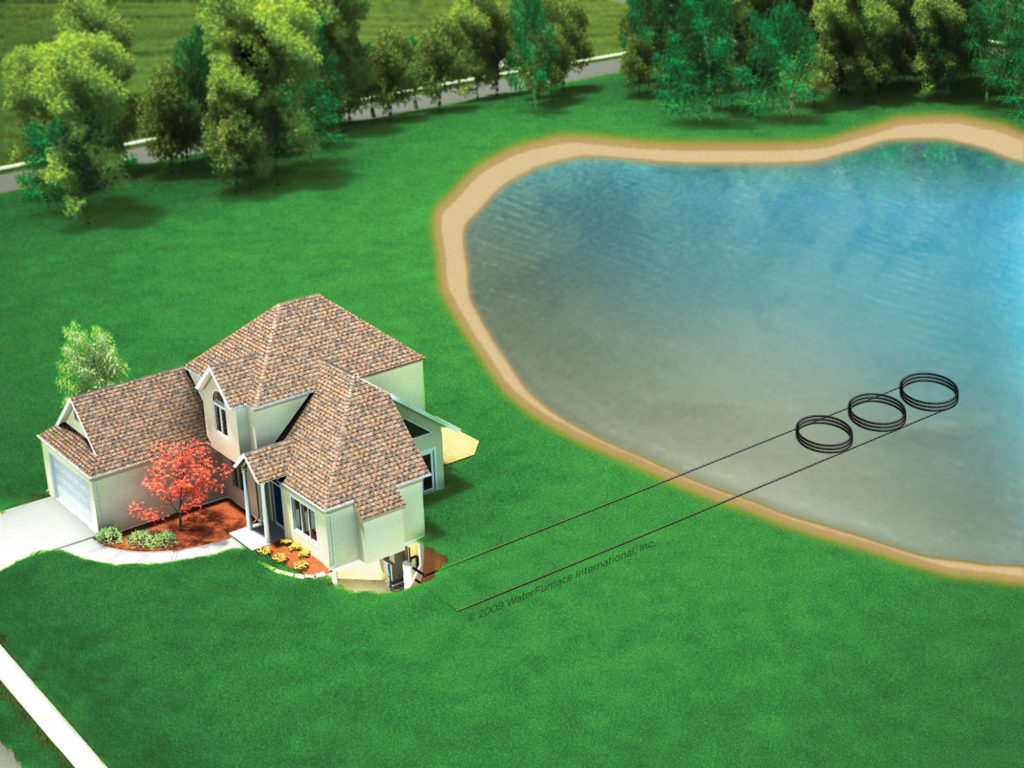

If you’re lucky enough to have a pond a half-acre or larger on your property, your home may be a candidate for a pond loop system. A series of coiled, closed loops are sunk to the bottom of the water body. The loop is connected to the house via more pipe laid in a horizontal trench. Water-to-water heat transfer is much more efficient than water-to-air heat transfer, so this type of geothermal system is highly economical and efficient.

Whichever loop type is required, bear in mind that the life of a typical geothermal heat pump is 15 to 20 years; loop systems can last 20 years or more. Forced-air systems will require a water-to-air heat pump, while hydronic radiant heating systems require water-to-water heat pumps.

Although geothermal heat pumps can be integrated easily with existing systems such as forced-air or radiant floor heating, you’ll need space in a utility room or basement for all necessary components. Where there is no ductwork in place, a delivery system will have to be designed and installed, preferably one that disturbs as few original walls and ceilings as possible. For a two-storey house, for example, it may make sense to install a split system, placing ductwork and an air handler for the first floor in the basement, with a similar set-up in the attic to serve the upper floor.

Designing and installing a geothermal HVAC system is a complex process. It goes without saying that this is not a do-it-yourself project. Look for a contractor/engineering firm with significant experience in geothermal installations, preferably one certified by the International Ground Source Heat Pump Association (igshpa.org).

Pro tip: The capacity of a geothermal system is measured in tons. A 3-ton setup usually works for a home of about 2,000 square feet.

Expect to do a little landscaping after the system is in, as shown in this historic geothermal install in the Hudson Valley.

Courtesy Hudson Valley Geo

Get a Tax Break

In February, federal tax credits were reinstated for residential and commercial geothermal installations in the U.S. The tax credits cover any geothermal projects begun since January 2017 and will cover new ones that get underway by January 2022. To meet the requirements, the system must use the ground or ground water as a thermal energy source to heat the dwelling. The system must also meet Energy Star standards in effect at the time of installation.

The credits provide a tax break of between 22 and 30 percent of the total cost of the system, including installation costs. For a $30,000 system installed during the window of maximum credits, that’s a potential cost savings of $9,000. State credits, where available, can bump up the after-tax cash savings significantly. In New York State, for example, a 4-ton system is eligible for a $6,000 rebate. That’s a lot of dough.

Types of Loops

The three most common types of loops for underground geothermal are (1) horizontal, (2) vertical, and (3) pond loops. All three require major excavation to lay the necessary piping.

1. Geothermal horizontal loop.

Courtesy Water Furnace

Courtesy Water Furnace

Courtesy Water Furnace

It’s Green

About 70 percent of the energy used by a geothermal heat-pump system comes in the form of renewable energy from the ground. According to the EPA, high-efficiency geothermal systems are on average 48 percent more efficient than gas furnaces, 75 percent more efficient than oil furnaces, and 43 percent more efficient when in the cooling mode.

Because geothermal pump heating systems do not burn fossil fuels to produce heat, they generate far fewer greenhouse gases than a conventional furnace. They also provide higher air quality because there are no emissions of carbon monoxide. In general, a 3-ton residential geothermal heat-pump system produces an average of about one pound less carbon dioxide per hour compared to a conventional system. Over a 20-year span, that’s enough to remove the equivalent of 10 metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere. If 100,000 geothermal units go into service in the next few years, it could save as much energy as removing nearly 60,000 cars from U.S. highways.

Visit dsireusa.org for tax incentives available by state.