Access ramps don’t have to be unattractive and clinical looking. This sensitive addition to this old house was constructed right onto the porch. (Photo: James C. Massey)

Most folks who own vintage houses have learned the value of planning ahead—for new roofs, new wiring, new plumbing, new kitchens and baths. New stuff in old houses pretty clearly calls for careful forethought to ensure a happy fit between modern lifestyles and aging buildings. But what about the fit between aging houses and aging owners?

Too often, we forget to consider what will happen when we find ourselves needing a bit of rehab. Leaving aside the broken bones and damaged spinal cords that can befall anyone at any age, most people will, sooner or later, need some help from the built environment. Millions of Americans have low vision, crippling arthritis, ailing hearts or lungs, problems with balance, flagging energy, or one of dozens of other physical disabilities that make living independently in their own homes problematic. If you, like many old-house lovers, intend to live in your treasured antique building for many years to come, understanding and addressing some of your future needs now, while you’re active or the building is under construction, can make it an even better place to enjoy a full and independent life.

The Aging Game

Many old row houses had trunk lifts, narrow elevators to comvey heavy loads to top floors—a handy helper for any age. (Photo: James C. Massey)

In the year 2001, 3.5 million baby boomers joined the ranks of Americans over the age of 55. Furthermore, AARP (formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons) tells us that fully 82% of people over age 50 want to spend their golden years in their own homes. Presumably that includes many houses that have been around for half a century or longer. As more and more people ask themselves how their existing houses can provide the safe, convenient surroundings older folks need, two new catch phrases have entered the remodeler’s vocabulary: aging in place and universal design. The National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB) is advising remodelers that they can’t afford to ignore the aging-in-place market that is, the one made up of old people in old houses. It’s the innovative use of universal design—the design of environments to satisfy the needs of many types of users—that makes staying in their old houses a viable option for aging owners.

No matter what your age, it’s never too soon to start thinking about how your house will work for you during the years when you’re most likely to need its help. Experts agree that the best time to consider changes to your living space is before—not after—you’re also being forced to think about hip replacements or live-in caregivers. In fact, many real estate agents advise that there’s nothing about a thoughtfully designed accessible house that’s likely to make it worth less when resale time rolls around. After all, even young people meet with the occasional temporarily or permanently disabling disaster. Even young people have friends or family members with disabilities whom they’d like to entertain comfortably and with dignity in their own homes. (Lugging visitors like sacks of potatoes from one floor to another may be well-intentioned, but it is definitely neither comfortable nor dignified for the lug-ees.)

So whatever your age, before you restore, rehab, or remodel an old house—preferably before you even buy—one consider these factors:

A back garden serves as a pathway to the house, which is used by the owner, who suffered a stroke. (Photo: David Duncan Livingston)

Location. If you’ve already bought your dream house, this may no longer be a negotiable issue. Generally, however, you want a neighborhood that is likely to be safe over the long haul for older folks, as well as for younger people and their children. You’ll want it to be convenient to the places you visit frequently, such as bus stops, libraries, food stores, your friends’ and families’ homes, doctors’ offices, and hospitals. Naturally you’ll want it to be affordable, too, both now and especially later, when your income is likely to be fixed at a considerably reduced level. With luck and some help from like-minded fixer-upper types, the rundown neighborhood you bought into because of its inexpensive housing stock will stay on the upside of the real estate market—in which case, so probably will your property taxes. That’s when a reverse mortgage on your lovingly rehabbed old house could make any amount of long-ago sweat equity and forethought seem like a very smart investment.

Access. Just getting into many old houses presents problems for all but the fully mobile. Not all exterior stairs have treads deep enough to accommodate an adult-sized foot, and the risers are often too high to be safe for either small children or older people. Add to those hazards the fact that many stairs lack handrails—much less on both sides, which is essential for people who are strongest on just their left or right due to stroke, injury, arthritis, or other disabilities.

Improving exterior access can be relatively easy or extraordinarily challenging. If there’s enough space around at least one entrance (front, rear, or side), there may be several options for improved access. If the space is constricted, as on a tight, urban lot, the options may be far fewer.

Wheelchair ramps, when they are carefully thought out and installed, don’t have to be the mile-long stretches of raw-looking lumber that all too often identify the homes of the elderly. (Muggers and scam artists, take note!) The standard, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) approved ramp is at least 36″ wide, with a grade of 1″ per 12′ of ramp, and with a railing on each side. (Note that not all persons with disabilities are in wheelchairs; some use crutches, canes, or walkers, or have poor vision. Wheelchair ramps are not necessarily the safest or most comfortable means of access for these people.) As it happens, some of the best ramps hardly register visually as ramps at all, because they are artfully concealed within porches or landscape features. Accomplishing that kind of efficient yet attractive design often takes time, money, and the services of a professional—all good reasons to start early and do it right while you can shoulder at least part of the work yourself.

The Philadelphia house passageway accommodates the turning of a wheelchair—complying with accessibility codes. No threshold between rooms makes for a smooth transition. (Photo: David Duncan Livingston)

Mechanical lifts are trickier and generally expensive, but they also may be installed unobtrusively behind landscape features or concealed by the building. Or they may be placed at the side or rear of the building, with an accessible path leading to the parking or sidewalk area.

If there’s room, probably the best solution for exterior access is to regrade the entrance into a gentle slope so that there are no steps to climb except, of course, for those who wish to climb them on their own. Regrading circumvents the possibility of destroying or defacing a historic, character-defining entry with a lift mechanism or ramp. It is also an excellent way to make the garden—which many an old-house dweller considers the true heart of the home—accessible to visitors who must use wheelchairs, walkers, crutches, or canes. You might even put in a few raised beds; sore backs attack gardeners of any age.

Indoors, old houses can present other obstacles: narrow doorways, narrow stairs, narrow halls, inadequate turnaround space for wheelchairs, steps up or down to additions, even raised thresholds. One or more of these impediments could turn your cozy castle into a prison. Doorways can be widened, of course, but in an old house that’s usually an unappealing idea. Hallways also can sometimes be widened, although the structural risks would need careful consideration. Narrow stairways could be reoriented to allow the use of stair glides (an inventive architectural feature made for this purpose). Even with a stair glide, there still needs to be room to rotate a wheelchair at the top of the stairs. Often there also must be room for a helper to stand and assist the disabled person.

One alternative to a stair glide is an elevator, which can sometimes be installed in a surprisingly small space. Some old houses already have elevators, usually in the small versions that once served as trunk lifts. Though these are typically too small to hold a wheelchair, if you have such a lift by all means keep it. Toting packages up and down stairs doesn’t get any easier with age! Modern, one-person elevators take up minimal amounts of living space. Sometimes it’s possible to add a vertical access corridor on a secondary facade at the rear or side of the house.

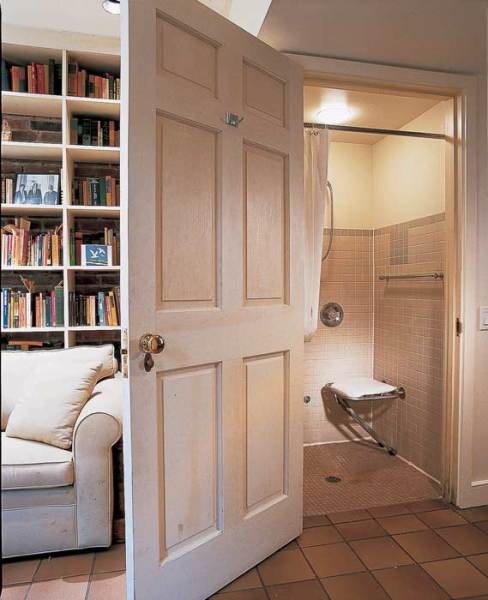

This shower stall includes built-in seating and a hand-held shower head. (Photo: David Duncan Livingston)

Bathrooms and Kitchens. Relatively few people will spend much of their lives in wheelchairs, but for those who must do so, bathrooms and kitchens can be frustrating places. Even nonwheelchair types can have trouble with counters that are too high or too low, cabinets and shelves that are too deep, faucets and door knobs that defy arthritic hands, tubs and showers that are impossible to get safely into, toilets that can’t be used without the help of another human being, or water that suddenly runs hot or cold when it should be just soothingly warm. There are remedies for all these problems, some cheap and common sense, some more expensive or complex.

The truth about kitchens and bathrooms in old houses is that they are the most frequently and drastically remodeled rooms in the house (the average kitchen remodel is said to be in the $30,000-plus range these days). This being said, if you’re going to drop a bundle on modernizing these spaces anyway, why not plan ahead for accessibility? Adjustable-height shelving and counters, located within easy reach of a seated person; lazy Susans that make cabinet corners usable; wall ovens with doors that swing out rather than down; flat stove surfaces that make moving pots and pans about less hazardous; rounded corners and softer materials on counter tops, lessening the chance of injury in the event of impact— these are all simple ways to make these utilitarian rooms safer and more usable for everyone, not just the elderly or the disabled.

In the bathroom, features such as roll-in, lipless showers and swing-out tub sides, while they may be essential to the disabled, are helpful to many other people as well. Mothers of young children, for instance, might well appreciate not having to hoist wriggling tots in and out of the tub. Sturdy grab bars firmly attached to studs around tubs and showers (on all three sides of the fixture; not just on one wall) are just good sense for everybody.

This kitchen allows the cook to do all food prep while seated at a sturdy country farm table or at pull-down shelving next to the stove. (Photo: Brian Vanden Brink)

Lighting and Electricity. Electrical service is a common source of frustration—and sometimes danger—in most old houses. By all means, bring the wiring up to code, but go a step further and make it convenient as well as safe. For instance, there never seem to be enough receptacles, and they’re never in the right locations “right” being in the waist-to-shoulder level, definitely not in baseboards or even, as in many old houses, on the floor. Wall light switches are too often missing or inconveniently located, and conventional toggle switches are sometimes hard to locate and operate. Sliding switches that can be activated with an elbow or a shoulder are cheap and easy improvements. Remote-control switches can eliminate the need to enter a dark room. Stairs and steps should certainly be well lighted to reduce the possibility of falls. However, it isn’t necessary or even safe to use the same high level of light at all times in all places. The sudden flash produced by turning on a 100-watt bulb in a dark room can lead to several minutes of blindness in a person with macular degeneration. Night lights may work better.

In the same way, exterior light and outside views are vital, but unshaded windows can become glaring sight dimmers and can also shatter privacy. Furthermore, conventional window shades and blinds can be difficult to operate. Fortunately, there are remote-control devices that can make this problem go away. Security systems and fire alarms are important components of safe old-house living for the elderly as well as for younger occupants. Since many older people are hard of hearing, alarms need to incorporate both bright, blinking lights and loud sounds.

Finally, the electrical service to the old house not only needs to be fully compliant with modern building codes, but it also should take into account that seniors are as computer reliant as younger people. Often, in fact, the Internet is a genuine lifeline for those who have trouble getting around outside their homes, offering the opportunity for dozens of activities that range from shopping for gifts and groceries to contact with doctors and pharmacists (not to mention family and friends). Old houses need to be wired for the ever-increasing demands of the electronic age.

Wall ovens that swing out rather than down eliminate crouching and bending. (Photo: Brian Vanden Brink)

Flooring. Falls are the leading cause of injury among the elderly, and the home is the most frequent site of falls. It seems obvious, but floors should be reasonably level and have nonslip, nonglare surfaces. Even small changes in floor levels will be safer when marked by a change in color or light. Thresholds are a frequent cause of stumbling. If necessary, they can usually be removed without permanent damage to the house, then replaced later, if desired.

Heating and Cooling. They are significant both from an economic and a health standpoint. Obviously, if you had to, you could retreat to just one or two rooms during very hot or cold weather, but efficient insulation and well-planned HVAC systems are crucial not just to the comfort but to the safety of older people. Furthermore, heating and/or cooling costs could make the difference between the ability to remain in a beloved old house and the need to move to a modern facility.

Among the many joys of old-house living is the fact that the house itself provides almost endless opportunities for change and growth. A bit of foresight can make those opportunities last a lifetime.