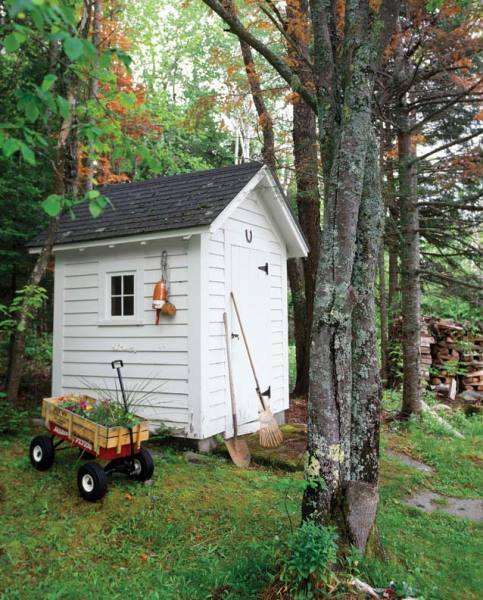

A Victorian-influenced outbuilding is set back to take in views of blooming flowers. (Photo: Eric Roth)

A few years ago on a trip to England, my sister and I had the opportunity to spend some lovely, lazy days at an ancient country inn. The setting was magnificent—the rolling green hills of Devonshire—but what made the place really special was a delightful walled garden, where, at the rear, sat an inviting glassed summerhouse. Converted from an old potting shed, this small building had a cushioned banquette inside, as well as a small open-air terrace with old-fashioned gliding chairs out front. Perched in these comfortable seats, you looked down the axis of two flanking perennial borders awash in summer reds, golds, and oranges toward the weathered stone of the seventeenth-century house. Every evening after dinner, digestif in hand, my sister and I would retire across the rolled lawn to this summerhouse, where we’d review the events of the past day and our plans for the next as the bees gently hummed in the flowers about us, until the setting sun finally put an end to this pleasant scene.

The hours spent in that summerhouse were so utterly charming that I immediately began pondering what particular elements made it so enticing. I finally decided that its appeal lay in the fact that the converted shed allowed us to appreciate the garden from within the garden, unlike so many other outdoor spaces—such as patios and decks—that provide visual enjoyment from afar. Here was a chance to experience the multi-sense pleasures of the garden—scent, sound, color—with an immediacy that was completely lacking in my own Boston landscape. I resolved then and there to make some corrections upon my return.

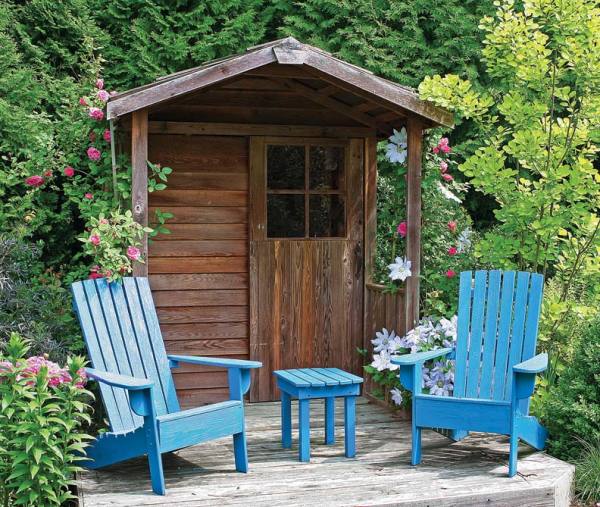

Michael Weishan added this sweet little shed to his own garden and built a small deck to sit and drink in his work. (Photo: Courtesy of Michael Weishan)

From little acorns tall oaks do grow, they say. And from seemingly innocuous plans such as mine, large headaches often emerge, as I can attest. For in my innocence, I decided to move an underused tool shed we’d installed in the vegetable garden during my “Victory Garden” years to a new location a hundred yards to the east in the orchard. Unwilling to entirely surrender its original function (after all, I still needed a remote site for tools), I had the brilliant idea of adding a simple sitting deck to the front of the structure to allow space for two comfortable Adirondack chairs.

It sounds easy enough, true. But the reality was fairly nightmarish. I won’t dwell on the multiple stings I received from a hidden hornets nest during disassembly; or the fact that the shed, which had been built from a kit, was so heavy in its partly-assembled form that it required expensive mechanized transport to its new location; nor how the process of moving the structure required removing, then reinstalling, several fences; nor the damage that rolling the thousand-pound beast caused to the intervening gardens and lawn…no, no, I will detail none of that. What I will share with you instead are some important lessons I learned in the process of re-creating my English summerhouse idyll.

1. The structure must have charm.

This might seem self-evident, but the vast majority of garden shed structures for sale at big box stores are as generic as the stores themselves. In my case, I had chosen our shed from a company that offers a wide selection of kits, and if you’re handy, this may be something to consider. Given a helper and a few basic power tools, you can have a small garden house up and running in a day. The advantage to building your own—aside from the pleasure of self-accomplishment—is that you have the option of selecting a size and design to fit your site. This last point is important, for to be effective, the structure needs to relate to the style of your home and garden. The easiest way to do that is to repeat on the garden house materials, colors, and features found on your home. Also, the building needs to possess a decent amount of architectural detailing beyond four walls, a door, and a roof: My shed came with two push-out articulated windows and a small, railed covered porch in front that doubled as the entrance and a seating area. Other options might include window boxes, weathervanes, decorative trim, you name it. Just make sure you take the overall style cue from what already exists on your property.

Consider adding water and electricity to yourstructure to charge power tools and water the plants. (Photo: Eric Roth)

2. The structure must relate to the landscape.

Remember, you’re adding a building to your garden, and if you don’t want it to look like Dorothy’s-house-dropped-from-the-skies, positioning the building within the landscape needs careful consideration. Garden structures work best when they are located on a direct axis with the house; or, if too far away, on a principal axis of the garden in which they are located. This generally means that the structure will sit somewhere on the perimeter. Symmetrical alignments to the side or rear are common, though I have seen a number of occasions where the garden house is located at, and becomes the center of, the garden itself. (Obviously in this case, its architectural features must be sufficiently interesting to make it a true destination.)

Once the location is decided, what’s important is to then settle the structure into the landscape; thoughtful plantings to the rear and sides will allow you to comfortably incorporate solid architecture into the garden. (One other word of caution here: Outbuildings are governed by ordinance in many towns, both as to size and set-backs from the property line, so be sure to check with your local authorities before purchase.)

3. The structure must be utilitarian.

Utilitarian in this case means that the garden structure must function well for its intended purpose. If, for example, the idea is to create an outdoor living area, the building must be conveniently located for such use, have enough floor space to accommodate the intended number of occupants, and possess whatever features are requisite to your goals. (Water is one; electricity another. With power supplied to the building, suddenly a whole range of options open up, from night-time use to a place to recharge battery-powered tools. Water is yet another.) And speaking of tools, even if your primary desire is to create a social space, it’s unbelievably handy to be able to whip out a pair of pruners to nip that wayward branch or pot up a favored annual without walking halfway across the world to the house or garage. Tools can always be tucked somewhere in a cabinet at the side or back, and I find that such mixed-use structures generally prove most useful in the end.

So, with these few tips delineated, I think its time I adjourn to my “orchard house” and settle in with a cool drink and good book to enjoy the pleasures of a warm, sunny afternoon, surrounded by gentle breezes and the sight of apples reddening on my trees. Sound inviting? It is, and readily achievable, if you think now about how you might incorporate a little “garden destination” into your landscape next season.