Whether completely out of sight or visible but discreet, options to heat and cool an older house are almost endless. We now have solar panels that seem to melt into the roof; radiant heat under a new tile floor; and state-of-the-art HVAC systems delivered by compact tubing or via cassettes concealed in voids between attic and ceiling. These minimally invasive systems are getting wider coverage, including in OHJ. What follows is in-depth, on-site coverage of two technologies, which have the somewhat confusing names “mini duct” and “mini split,” plus updates on other techy ways to save energy without ripping out plaster.

DID YOU KNOW? In a boon for older homes built without it, conventional ductwork for heating and cooling may soon become a thing of the past. New and versatile technologies make it possible to heat, cool, humidify, and even supply hot water to an entire house with minimally invasive components that are sized and placed according to room dimensions and specific energy loads.

In Unico’s system, the plenum that connects the air handler with the small ducts is about one-third the size of conventional ducting. Jim Polson

Mini Duct Systems

Mini-duct outlets are small and may be ordered in colors that match the ceiling or wall. Jim Polson

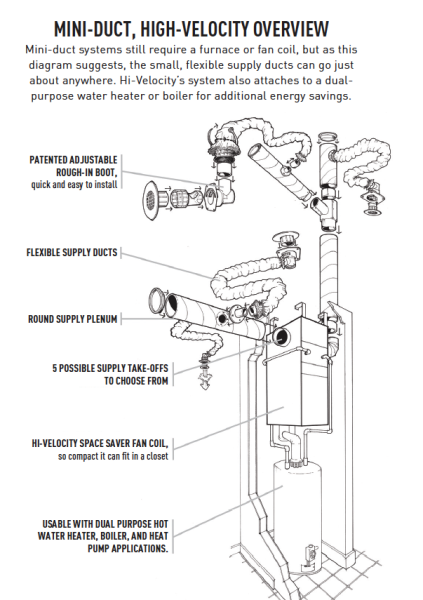

Old houses simply don’t have room for the conventional ductwork a whole-house, forced-air heating and cooling system requires. Ductwork consumes headroom in basements and in kitchens (as soffits). Installing the wall ducts often means losing precious storage space in closets, or disturbing original plaster and even finishes like expensive wallpaper. Mini-duct systems —offered by two companies based in the U.S., SpacePak and Unico, and one in Canada, Hi-Velocity—literally work around those problems with small ducts made of flexible tubing.

At about 3″ in diameter, the ducts are small enough to be routed between studs in walls and in cavities under floors and above ceilings. The system works by aspiration, quietly pumping warm or cool air at high velocity throughout house. This creates a gentle circulation pattern that produces relatively even heat from floor to ceiling. Rooms typically feel more comfortable, even at lower temperature settings. The compact ductwork has also been found to leak less than conventional forced-air ducts, which means even more energy savings.

Mini-duct illustration. Courtesy Hi-Velocity

Mini-duct systems are usually equipped with the latest in air filtration and humidification systems. Tests show they’re capable of removing up to 30 percent more humidity than a traditional forced-air system. (The drier the air on a hot summer day, the cooler the house will feel.) The system can add humidity in cold, dry weather for increased comfort. Installation is not without its disruptions, but outlets are smaller than conventional floor grates and can be trimmed to accent or conceal them.

With minimal ducting, a mini-split compact cassette evenly distributes cool or warm air through a vent not much larger than a conventional forced air return. Courtesy Mitsubishi Electric

Runtal North America Shop Tour

It’s possible to visit the Runtal North America showroom in northeastern Massachusetts and have no idea that the company’s innovative flat-panel radiators are fabricated, start to finish, in the same building. “We like to call it a combination of Swiss technology and Yankee craftsmanship,” says Owen Kantor, the long-time vice president of marketing and sales.

Runtal’s flat-panel radiator virtually disappears, taking up no floor space.

“Few companies can say they manufacture in the U.S. Not only have we been making radiators here since 1989, but we also continue to expand the factory.”

Runtal’s sleek, European-style, flat-panel hydronic radiators are composed of thin, flat panels attached to heating fins, held in place on either side by square, tube-shaped headers that carry heated water to the panels. The entire assembly is a mere 1 /” thick.

Small, square notches are punched into steel sheet metal at precise locations to fit finished fin coils to the radiator panels.

Installed along baseboards or cabinet toe-kicks, a one- or two-panel horizontal unit can virtually disappear. Radiators may be painted in any of 100 colors to coordinate with wall color or wood finishes, or even appliances. “Architects like our product because they can make it invisible in a traditional home,” says Jonathan Wiberg, national sales manager for Runtal’s residential division.

Panel assemblies can be curved to fit radius spaces like a bow window, or welded together in a three-sided configuration to fit a bay window. Electric panels—introduced about seven years ago—are installed by an electrician; hydronic models require a plumber. Like traditional radiators, these work through a combination of convection and radiant heat.

A hydraulic press bends the notched steel to create the fins. (The corrugated pockets capture hot air and channel it upward.) The completed fins roll up at the end of the run and are stacked for transfer.

The company also offers flat and round-tube towel radiators, assembled, painted, and finished at the Massachusetts factory, and several items made in Europe. Runtal also offers sleek radiators for steam systems under its Steam Radiators Division.

I watch as two sequential machines form the fin coils. Sheet steel passes through the first machine, which punches small, square holes at precise locations. (These openings permit the finished coils to mount to the back of the radiator.) Then, a hydraulic press crimps and bends the notched steel, creating corrugated pockets that will capture hot air and channel it upward. Panels will be joined to square tubes known as headers that hold the panel assembly in place. First, the header tubes are punched with uniformly spaced holes, which allow heated water to flow into the flat panels at the front of the radiator. Headers are cut to length and fitted with end caps, pounded into place and welded smooth. A threaded connector—to plumb the radiator to the hot water heating system—is drilled into each header.

Steel flat tubes—future panel fronts—are cut to length with a circular saw.

Now the flat panels and headers are ready to be joined. An automated arm slides a flat tube into place on the header, where a robot welder joins them. The sequence is repeated until all the flat tubes are in place.

Next, a worker feeds the unit face-down into another machine. He places a length of fins, cut to length, on the back of the flat tube grid. The fins are spot welded between the folds to the heating tubes.

At Runtal North America’s factory, Duane Barnard TIG-welds fins to the front panels.

A finished top grille and mounts for threaded bolts are attached; bolts help level the radiator on the wall. Fully assembled, the radiator is tested by pumping air into it and submerging it in water. If no bubbles appear, it passes; when dry, it’s sent to the paint line. Sprayers apply electrostatically charged epoxy particles to form a skin in the color of choice. In just over two hours, a flat panel radiator is ready to ship.

Completed panels and trim covers pass through the enclosed paint station, where they’re manipulated by Miguel Dia and sprayed in a single pass. Panels dry briefly, then the color is baked on at 400 degrees.

Owen Kantor and Jonathan Wiberg in the Runtal showroom, with a custom towel radiator.

Mini Split Systems

Mini split systems are so named because a single power pack on the outside of the house can power one, two, or more heating and cooling units on the inside, without internal ductwork. The technology has been available for a couple of decades but is constantly evolving to meet the demands of both the new-build and retrofit markets.

No need for ductwork with these Slim Duct air handlers, which tuck into voids between floors. Courtesy Fujitsui

The Halcyon system from Fujitsu, for example, eliminates the need for an evaporator unit as well as bulky ductwork, freeing up space in the attic and basement. Thin copper tubing pumps refrigerant directly to discreet, wall-mounted or concealed units throughout the house. Remarkably, the units work in reverse when it’s cold. Even though the system runs on electricity rather than other fuels, a whole-house, mini-split system can cut energy bills by 25 percent, simply because the system does not use ductwork.

While wall-mounted units placed on interior walls are most familiar, newer delivery systems include hidden Slim Duct units mounted above or within the ceiling. Another option is the compact ceiling cassette. Although the unit is larger, measuring 2′ x 2′, only the grille shows in the ceiling. Cassettes use the latest in turbo-fan technology to distribute chilled or heated air evenly.

A standing-seam metal roof from Bridger Steel, painted Colonial Red, has a solar reflective index (SRI) of 36, meaning it qualifies for LEED credits as a “cool roof.”

Keep the Heat Out

In the market for a new roof? Look at the SRI (solar reflective index) on the color chart. A pitch-black roof may have a rating of zero, pure white as high as 100. The higher the index, the more the roof reflects sunlight, keeping heat out of the attic and the house. Cool-roofing products are made of highly reflective and emissive materials that stay 50–60°F cooler than traditional materials during peak summer weather. Asphalt roofs use solar reflective granules. With metal roofs, cool-roof colors are created using reflective paint. Bridger Steel’s 29 Gauge colors, for example, are almost all cool roof-certified (exceptions: black, Galvalume, galvanized). Cool-roof alternatives exist for clay or concrete tiles, normally with a reflectance of 10–30 percent. By adding highly reflective pigments, manufacturers have boosted it to 25–70 percent.

Insulation Update

Hiding out of sight, insulation is one of the best ways to make a house more comfortable and energy efficient. Old-house options usually boil down to adding batt or spray-foam insulation in the attic, and blown-in, loose fill in outer walls. While you might not want to use foam on 200-year-old beams or fieldstone walls, this method is effective in basements and crawl spaces. Combined with a vapor barrier on the floor, dense closed- or open-cell foam is superior at blocking penetration, especially wind-driven cold. Toxic when wet but inert once dry, spray foam requires professional installation (or a self-certification class and an OSHA-approved protective suit). One- and two-part spray-foam kits or cans (DAP, etc.) are user-friendly; use them to seal small voids around window frames, sill plates, and electrical devices.