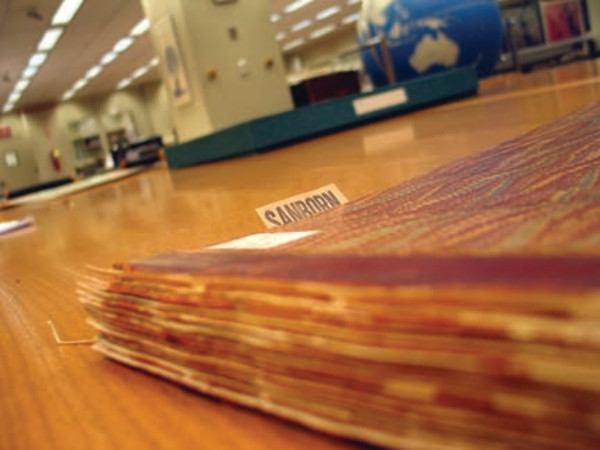

Bound by city and organized by year, the collection of original Sanborn maps is housed at the Library of Congress. (Photo: Karen Smith. Sanborn maps reprinted/used with permission from the Sanborn Library, LLC)

For more than 100 years, the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company painstakingly recorded every building in every major population center in the United States. Sold to regional groups of insurance underwriters, Sanborn maps provided detailed information about residential, industrial, and commercial buildings, including height and materials, fenestration, roofing, lot lines, water access, and block-to-block infrastructure, in more than 12,000 places in North America. Although they were discontinued in 1970, Sanborn maps—now held in many local historical societies and libraries (you can even find Sanborn maps online)—have become an important reference tool for homeowners, business owners, preservationists, urban planners, and architects looking to locate detailed information about a structure.

“In lieu of extant architectural drawings, they are the best guide you can find,” says Vincent Brooks, senior records archivist at the Library of Virginia. “They give you construction materials, exterior dimensions, roofing information, and, since they were updated every year, you can see changes over time.”

Plotting the Course

In the late 19th century, the advent of lithographic printing and the extension of rail lines collided with a near tripling of the U.S. population to create a booming market for insurance-based mapmaking. As new “fireproof” construction materials gradually appeared on the market to replace traditional wood and cast iron, insurance companies discovered a need to know what kinds of structures they were insuring before issuing policies. Between 1850 and 1900, companies like Aetna and Hartford Fire Insurance Company competed to track new and existing construction of homes, businesses, and property interests. Established in 1867, the Sanborn Fire Insurance Company’s map division came to dominate the industry by doing two things well: producing readable, uniform maps of towns and cities, and systematically absorbing local map companies. In 1883, the Sanborn Map Company began registering their maps with the copyright division of the Library of Congress, preserving a wealth of information for today’s homeowner. “Depending on what city you’re in, and depending on when they instituted a building permit process, Sanborns could be your only source for information,” notes Brooks.

Each Sanborn map was drawn at a scale of 1″ to 50′ on a uniform 21″ x 25″ sheet, cross-ruled in 1″ squares. What makes the maps especially useful for homeowners is their consistency from year to year and their color-coded key, which indicates a wealth of easily identifiable detail: type of construction (concrete block, brick, stone, or wood frame), fireproof or not, cornice material, cladding material, wall thickness, type of shutter cladding (iron or tin), and exact window sizes. Because of their clear and consistent graphic style, Sanborn maps are particularly easy for non-professionals to read and use. In recording these kinds of details, the company inadvertently provided a crucial tool for historic preservation officials—as well as the average curious homeowner.

“It gives you a gross level of information, like a footprint—was there a porch, was there an addition?” says Kim Chen, a historical architect whose firm has completed projects up and down the East Coast. “If you can get the color versions of the map, it will tell you if the building is brick or frame. Sanborns are just one piece of the puzzle, but they’re a great first step.”

Today, the collection of original Sanborn maps at the Library of Congress (donated in the ’60s) spans from 1867 to the late 1950s, but you don’t have to travel to Washington, D.C. to take advantage of them for your next restoration project. More than 50 state, local, and university libraries across the country were gifted with duplicate sheets from the collection that represented their regional areas. In addition, many libraries and universities subscribe to ProQuest’s Digital Sanborn collection, a searchable, printable database of all the Sanborn maps in the Library of Congress’ collection (plus those up until the 1970s), reproduced in black and white. Whether they’ve been digitized, microfilmed, or remain in their original large-format printed state, Sanborn maps are one of the most accessible and useful research tools for anyone with a little patience and an hour or two to spare.

A 1905 Sanborn map showed the configuration of Barbara Smith’s narrow 1895 Italianate, which has changed little over the years. (Photo: William Richards)

Practical Applications

“Property assessments are great, deeds are wonderful, but I depend on Sanborns to tell me if there have been any changes,” says Barbara Smith, a Virginia homeowner who writes local house histories. Her 1895 Italianate home, barely 10′ wide, is a two-story wood-frame structure tucked into the heart of Richmond’s historic Church Hill. As the neighborhood expanded during Reconstruction, she explains, the economics of homeownership became more favorable for the working class. In 1895, Richmond paperhanger and upholsterer Irvin Hudson built Smith’s modest home, just two blocks from one of the city’s main thoroughfares.

“It’s a funny little house,” she says, “but it says a lot about how a person like Irvin Hudson lived. With family nearby and a trolley line he could use, he represents an important chapter in Richmond’s history—and where he lived is a big part of that.”

Smith found the peculiarities of her property’s history useful as she prepared to put it on the market in early 2009. Remarkably, the house remained in Hudson’s family for 85 years, which she determined through city records. By tracking the home on successive Sanborn maps, however, she determined that little about it had changed beyond some cosmetic, electrical, and HVAC upgrades. “It’s good information for a potential homebuyer,” says Smith, “and it’s information that you can back up with evidence.”

Sanborn maps not only provide data about individual structures, but also can reveal information about the texture and character of neighborhoods. “They help me understand that, say, between 1918 and 1924, there were six houses in a neighborhood. Then you look at the 1932 map and see that 300 houses were developed by that time,” says Chen. “You start asking yourself, why did this happen?” The extension of city trolley lines often brought development, as did the construction of a factory nearby. Where there was local employment and accessible transportation, especially before the automobile’s dominance, there was housing. “Now you know something about the social and professional fabric of your neighborhood—and your house,” notes Chen.

The maps can reveal details about your surroundings that you may never have suspected. While researching the background of his home, Jeff Elliott, a homeowner in Santa Rosa, California, made a surprising discovery about a two-story circa-1880 Greek Revival home on his block.

“The house is an oddity on the street,” he notes, “where nearby houses are single-story cottages or Western ranches built between 1930 and 1950.”

After comparing two Sanborn maps from 1908 and 1937, Elliott discovered that the original site of the house was nearly a football field away from its current location. The building began life as the farmhouse on land that was eventually turned into a mid-century subdivision. “At some point after 1908, they lifted the old girl and moved her—probably with mules pulling a platform over rolling logs—while spinning it around 180 degrees at the same time,” Elliott says. “Quite a trick.”

Of course, the most handy—and common—use for Sanborn maps is to provide essential details that can help inform restoration decisions. For instance, on Comstock House, Elliott’s own home, an adjacent garage on the property presented “some serious structural issues that needed prompt attention,” he says, in turn raising questions about the outbuilding’s origins. “I needed to know whether I should approach it as a historical restoration.”

By comparing 1908 and 1937 Sanborn maps of his home, Comstock House, Jeff Elliott discovered that a detached garage was added sometime in the early 20th century. (Photo: Jeff Elliott)

By studying the available Sanborn maps for his area—1904, 1908, and 1937—Elliott confirmed several things. First, the garage was not original to the house—it was built later, sometime between 1908 and 1937. One could then rule out the possibility that it was an existing carriage house later converted to a garage, as its probable construction dates correspond to the introduction of the affordable automobile. Second, and more curiously, Elliott noticed that the building had its own half address (767½), which corresponded to the main house’s 767 street number.

Although Elliott still has more research to do—“Does that half address impact a possible future conversion from outbuilding to ‘granny unit’?” he wonders—he calls this quick research project “a perfect example of how useful the maps can be.”

In addition to helping uncover invisible changes that have happened to a property over time, Sanborn maps also can clarify visible changes that seem out of place.

Carl Nittinger, a historic preservationist in New Jersey, relays a story about a double house in Haddonfield, New Jersey, with symmetrical detailing. While the local historic preservation commission approved the reconstruction of a front porch on one side of the Queen Anne structure, something was slightly off about its appearance compared to the other side.

Part of the problem lay in the fact that the porch was built in concrete, instead of a more authentic wood decking system, but Nittinger also noticed that the porch seemed to protrude from the building in an “acutely apparent” way. “I consulted the historic Sanborn map of the neighborhood and found that the footprint was not consistent with the original roof, and the new, angular replacement porch extended beyond the Sanborn footprint,” he reports. “It’s a good example of how a restoration project could have been executed in a historically correct way by consulting the Sanborn.”

On another level, the original Sanborn maps are handsome objects in and of themselves. All colored by hand in the Sanborn home office, some maps show richly detailed and dense city streets, while others seem almost abstract in their careful register of sparser industrial tracts.

The insurance division of the Sanborn Company is long gone, having evolved into a provider of data for geographic information system (GIS) mapping services. Yet Sanborn’s early maps remain, not just as tools, but also as vivid links to the past.

William Richards is a writer based in Richmond, Virginia, and editor of Inform: Architecture and Design in the Mid-Atlantic.

Web exclusive: Click here to find Sanborn maps online.