In order to mitigate spalling on the Second Bank in Philadelphia, titanium orthopedic screws were installed into marble columns. (Photo: Milner + Carr Conservation, LLC/National Park Service)

The waters of restoration were uncharted for most old-house owners 35 years ago. Little information on the subject was available, leaving homeowners to their own discretion when it came to fixing up their houses. Fast-forward to today—the restoration of old houses has become a multimillion-dollar industry, producing a plethora of magazines, TV shows, and web sites. Needless to say, much has changed in the world of preservation between then and now. We talked with a few specialists who were there in the early trial-and-error days and learned that, while the goals are still the same, the preservation movement has come a long way.

Changing Attitudes

The 1970s were a time of great change in the world of preservation. The Historic Preservation Act was passed in 1966, and by 1976, the Tax Reform Act removed the incentive to demolish older buildings. In 1978 the Revenue Act established investment tax credits for the rehabilitation of historic buildings. These economic incentives led more people to take a chance on old houses.

“Because of these changes, preservation moved much closer to the mainstream of American life, being seen as a form of environmental stewardship as well as a satisfying means of communing with the past,” says New Hampshire state architectural historian Dr. James Garvin. “In 1973, large-scale urban renewal demolition was still going on in many cities. Today, old neighborhoods are sought out as places that offer preservation opportunities and a high quality of life.”

Practice Makes Perfect

In 1987, lightning struck the Jethro Coffin House (also known as the Oldest House on Nantucket), causing major damage to the roof and threatening the entire structure. (Photo: Nantucket Historical Association)

“Thirty-five years ago, there were very few trained preservation professionals,” notes OHJ founder Clem Labine. “James Marston Fitch’s pioneering historic preservation program at Columbia University had only started in 1964, and the Association of Preservation Technology (APT) was founded in 1968. In 1973, the world of preservation was still an amorphous entity. Amateurs and professionals alike were learning by doing.” By contrast, a number of schools around the country now offer historic preservation courses for both graduates and undergraduates.

“Historic preservation consulting and the practice of preservation architecture are far more pervasive and available than ever before,” adds Garvin. “Every state has a State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), and most SHPOs offer technical assistance to organizations, government agencies, and private owners.” The National Park Service’s Preservation Briefs also debuted in the 1970s, and today are all online for the old-house restorer to peruse.

To shore up the building, broken rafters were spliced together, and a new roof—designed to stand up to harsh island winds—was placed over the old one. (Photo: Nantucket Historical Association)

Judy Hayward, executive director of Historic Windsor, Inc. and the Preservation Education Institute, also cites the increasing number of people working in traditional trades as a fundamental shift in the preservation movement. “We went through a period in the mid-20th century where building practice and materials changed dramatically,” she says. “Many traditional tradespeople encouraged their children to pursue work in other professions, so there was about a 50- to 60-year break in the widespread practice of traditional building crafts. Thirty years ago, that trend began to change, and we began to renew our understanding of the skills it takes to be proficient in a trade.” This shift, she adds, also afforded many women a professional role in the preservation world—not unlike the genesis of the Arts & Crafts movement in the late 19th century.

Labine agrees that major changes have come about from old crafts that have been rediscovered. “In the 1970s, the industry reinvented the lost process for making encaustic tile,” he says. “The art of woodgraining was brought back from the edge of extinction, and marbleizing and stenciling texts from the 19th century suddenly found new readers.”

Technology and Materials

While the past 35 years have seen a resurgence in traditional trades and methods, there’s no discounting that technological advances have also played a role in furthering the preservation movement. “Historic paint research has benefited from more sophisticated microscopes, building investigation from miniature video cameras that can be inserted in wall cavities, and so on,” says OHJ editor-at-large Gordon Bock. “There’s no underestimating the impact of cordless tools, which are now made for almost every conceivable purpose.”

It’s also easier than ever to find the materials necessary for finishing a restoration project, thanks to a burgeoning industry for historic building materials. “In 1973, old-house restorers had few resources for historic paint colors or moldings, and almost nothing in the way of truly accurate decorative items like wallpaper, hardware, or light fixtures,” says Bock. “Now there’s a thriving industry that continues to expand.”

First, Do No Harm

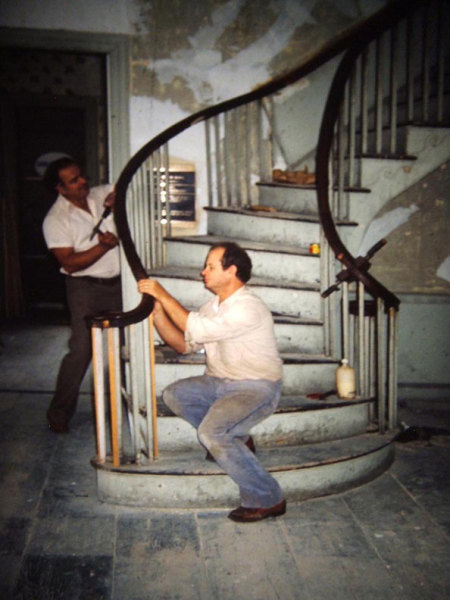

During a significant restoration of the Federal-style Shirley Eustis House in the 1980s, the home’s distinctive curved staircase was restored to its former glory. (Photo: Frederic C. Detwiller)

“Reversibility is the greatest change that I’ve seen over the past 35 years,” says architect John Milner. “In the future, we may find better methods of handling a preservation project, so we need our work today to be easily reversed.” Preservation methods of the past did not always take this notion into account. For instance, spreading epoxy over a masonry wall was a way to take care of spalling stone, but that epoxy is a permanent fix, says Milner, who recently helped restore the 1824 Second Bank of the U.S. in Philadelphia. Milner’s team stabilized spalling on the bank’s monolithic blue-marble columns by inserting titanium orthopedic bone screws, which can later be removed if a better method is discovered.

When the Jethro Coffin House (known as the Oldest House on Nantucket) was torn apart by a lightning strike in 1987, Milner was called on to find the right solution. “There were a lot of ethical and philosophical questions raised about how to put the house back together,” he says. While the prevailing thinking called for inserting a steel frame into the building, Milner chose the less invasive method of splicing broken rafters together by inserting plates and using an epoxy adhesive. He also added a new roof over the existing one that could handle the island’s wind load codes.

Sometimes even the best-intentioned restoration methods of the past could do more harm than good, Milner points out. Case in point: the restoration of the 1798 Octagon House in Washington, D.C., which included adding steel beams and concrete floors. These new materials were later removed when they proved to be incompatible with the old building, causing irreversible damage to the historic structure.

Recent projects at the Shirley Eustis House include saving the nearby Ingersoll-Gardner Carriage House by dismantling it and moving it to the property. (Photo: Frederic C. Detwiller)

Seeing the damage certain materials can bring to a structure, preservationists and restorers have begun to take a more cautious approach to projects. “We’ve learned to be conservative and appreciate more than ever the value of traditional repair methods for materials like wood, stone, and ceramics,” says Bock.

“We’re only now starting to amass a track record on how some restoration methodologies perform over a long time, and in some cases, this information leads us to reverse earlier thinking, such as in dealing with moisture,” he continues. “Early on, one school of thought held that it was appropriate to try to seal some building materials from moisture intrusion—say, by spraying porous building stones with high-tech coatings or painting all sides of porch floorboards and railings. Now we know that this approach sometimes traps moisture within the material—the exact opposite of the hoped-for protection.”

Above all, we’ve learned that each building is different and needs to be evaluated individually. There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to repairing old houses. And sometimes, even the new rules of preservation need to be broken in the name of doing less harm.

Reaching Our Goals

In 1973, only those houses dating before 1830 were deemed worthy of preservation. “If you couldn’t call it Colonial, it was a candidate for ‘modernizing’ and remodeling,” says Labine. “One of the primary missions of Old-House Journal was to name, study, and romanticize house styles from 1840 to 1940. We found that once people knew their home had a ‘style,’ they were much more interested in restoring it.”

“Today, there is much more regard for preserving neighborhoods and vernacular or cultural landscapes as well as great individual examples of architecture,” notes Garvin. “Federal and state governments have adopted historic preservation statutes and rules that make preservation part of public policy.”

Hayward also agrees that preservation is more widely accepted today. “It seems the norm now, but 30 years ago, it was almost revolutionary. It has been a combination of governments, nonprofit groups, private developers, homeowners, and professionals who have brought this about through hard work, tax incentives, sweat equity, and capital.” In other words? The work you’re doing right now on your old house could be shaping the course of preservation for the next 35 years.

Nancy E. Berry is the editor of New Old House, and is currently restoring an 1870 Queen Anne on Cape Cod.