Many of the historic buildings in Denver with brick delamination problems date from around the turn of the 20th century. Construction varies from cheap buildings to this handsome ca. 1909 house. Elizabeth J. Wheeler

Since few trees grow in the arid plains at the base of Colorado’s majestic Rocky Mountains, most of Denver’s beloved old neighborhoods are built from brick. After all, clay is plentiful where mountains loom, and early Denverites learned the benefits of brick in a big way. Many of the first houses in the Queen City of the Plains were built rapidly from logs, then consumed in a deadly fire that nearly destroyed Denver City, as it was known in 1863. Shortly thereafter the mayor proclaimed that all future buildings would be constructed of fireproof materials.

In the following years, gold, ranching, railroads, and healthful air for treating consumption (tuberculosis), brought thousands of people to Colorado, and dwellings were built quickly to house them. By 1900, 206 brickyards dotted the Denver landscape. For decades, the walls appeared to be steady and strong, but after a century, some of the houses are starting to show structural failure. The outer layers of bricks are separating from the bricks behind them, a condition called delamination that can lead to their collapse. Though the causes of this condition are not unique to Denver, it’s a recurring problem in the city, so they have a lot of experience that can be applied to many buildings across the country.

Though the bulk of many historic brick walls are composed of common brick that is hidden from view, what we see on the exterior is a layer of veneer brick—here peeled off the wall. Nancy Snyder

Degrees of Separation

Though the bulk of many historic brick walls are composed of common brick that is hidden from view, what we see on the exterior is a layer of veneer brick—here peeled off the wall. (Photo: Nancy Snyder)

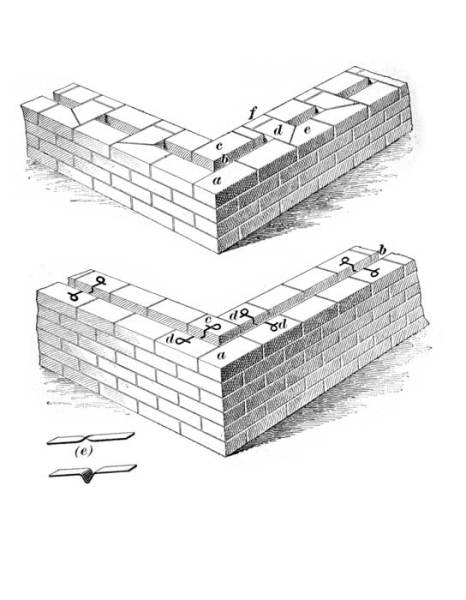

Age alone is not the cause of the separation; it’s also inherent in the construction. For centuries, the way to build a brick or stone building was to make the walls solid, load-bearing masonry. Finer brick or cut stone might be reserved for the finished faces, and lesser-quality brick or rubble used for infill, but each wall was still a monolithic mass, with tie-bricks or stones placed strategically across its thickness to knit the wall together. In the late 19th century, though, the solid brick wall was supplanted by the cavity wall, a European practice that was supposed to have insulating advantages. In a cavity wall the wythes (layers) of brick are separated by an air space that runs up the wall, with header bricks laid perpendicular to the face of the wall to tie the wythes together.

Unfortunately, during the hasty years of Denver’s construction boom, shortcuts were common. Some bricklayers did not take the time to always install a header course of brick when tying the multiple wythes together. Some embedded twisted wire or metal ties (common products at the time) in the horizontal mortar joints to tie the outer bricks to the inner ones. Other masons would angle a partial brick, called a queen closure, across the cavity, hiding it behind the outer wythe of bricks. In some cases, the masons altogether eliminated header courses—bricks laid perpendicular to the wall face in a horizontal stripe—because the homeowner or builder wanted a smooth, uniform look.

Environment took its toll too. “Denver’s sunny days and cold nights are the real culprits,” notes Diane Travis, technical advisor of the Rocky Mountain Masonry Institute, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to increase understanding and use of masonry. “When it rains or snows, brick becomes saturated,” she explains, “Then the water expands 9 percent when it freezes.” The constant freezing and thawing, called freeze-thaw cycles, can fracture even tough materials like brick, block, or stone. Once the outer wythe of brick starts tearing away from the inner wythes, it creates a vertical crack between the layers of the wall. “Broken brick accumulates in these fractures,” adds Travis, “and this debris forces the crack to get wider and wider.” Houses in climates where there are significant temperature swings might also be subject to this damage.

By the 1890s, manuals noted several ways to hold together brick cavity walls, such as using bricks or manufactured metal ties. Int he past, masons stabilized cavity walls with tie rods similar to joist anchors used in mill buildings. National Archives Association

By the 1890s, manuals noted several ways to hold together brick cavity walls, such as using bricks or manufactured metal ties. Int he past, masons stabilized cavity walls with tie rods similar to joist anchors used in mill buildings. (Courtesy: National Archives Associates)

What to Do About Wythes

The first step in addressing the problem is determining where the wythes are delaminating. The simplest method is to sight down the face of the wall with one eye, studying the surface for bulges. Another approach is to look inside the wall cavity with a borescope, an inspection device consisting of long rigid or flexible tube with a lens at the end. After boring a small hole in a mortar joint, an engineer can insert the borescope and look behind the veneer bricks to examine the cavity and the condition of tie bricks or metal ties.

Historically, the fix for bulging and out-of-plane walls was to install steel through-wall ties to hold the separating wythes together. These installations are not hard to identify because the masons typically used steel bars or S-shaped plates on the wall face to spread out the load and keep the tie from pulling through the brick veneer. If the delamination is severe, the traditional way to repair the brick veneer bulge has been to tear the unstable bricks off the wall and reinstall them with proper masonry ties, a costly and time consuming method.

Today there are stainless steel masonry anchors on the market that can be inserted in the wall, not to pull the bulges back into place, but to tie the wythes together and keep them from continuing to peel apart. The ties can be installed by working on either the exterior of the wall (which avoids disrupting household activities), or the interior, say while remodeling the living space. Diane Travis recommends installing the ties from the interior face of the wall. This way the ties are totally invisible and they are not exposed to weather at all.

Masonry ties are ideally installed in the mortar joints. This requires skill on late 19th century “butter joints” which are both incredibly narrow and usually colored to match the brick. (Photo: Nancy Snyder)

Masonry ties are ideally installed in the mortar joints. This requires skill on late 19th century “butter joints” which are both incredibly narrow and usually colored to match the brick. Nancy Snyder

Though each manufacturer has their own version, these ties are basically thin spirals that can be countersunk into the wall so they are almost invisible. They are also flexible so they allow the wall to move and dissipate forces without cracking the masonry or causing other damage. Michael Schuller, PE, a Colorado-based consulting engineer specializing in the repair of masonry buildings recommends these anchors because of their adaptability and effectiveness. “We have used these ties on projects throughout the United States to tie historic facades back to the structure,” says Schuller.

Ties in Practice

John Voelker, a mason who has specialized in preservation of historic masonry for 25 years and helps teach the historic preservation certification class at Rocky Mountain Masonry Institute, is another advocate.

To demonstrate the technique during a certification class, Voelker begins by boring a small pilot hole into a brick wall. Voelker explains that ties are driven into mortar joints, not the bricks or other masonry units, at intervals of 16″ horizontally and vertically. Next he loads the tie into the power driver attachment fitted to a hammer drill. He then drives the tie into the wall until the outer end is fully recessed below the face of the brick.

A shortage of timber but ample clay has given Denver a rich tradition of brick masonry, extending right up to the era of this mid-20th century ranch house. (Photo: Elizabeth Wheeler)

A shortage of timber but ample clay has given Denver a rich tradition of brick masonry, extending right up to the era of this mid-20th century ranch house. Elizabeth J. Wheeler

Finally, he grouts the tiny hole with a small amount of mortar of the same color and composition of the original masonry. The ties come in several different lengths to accommodate the various layers, wythes, or courses, of brick used on a house. The process is the same for an interior application except the small hole is covered with plaster or drywall.

The total time it takes to repair brick walls with this system depends on the size and condition of the home. It is not uncommon for the whole process to be completed in a few hours or a few days. Voelker has used this system in his restoration projects for over a decade. “It is a great solution for unstable veneers on historic properties,” notes Voelker. “When it’s done correctly,” he adds, “no one will know that I saved a client’s brick wall from collapsing.”