A mere seven employees make all mouldings from scratch. Each piece of trimwork “goes into the moulder rough and comes out the other end as a finished piece,” says manager Mitchell Powell.

Mitchell Powell with one of Driwood’s ornate, embossed cornices.

When we spoke, Powell was especially pleased the company had finished a set-full of oversized mouldings for a big-budget Netflix heist film, “Red Notice.” Powell told us, “We just shipped that out today.”

Driwood has been in the Powell family for three generations. Powell’s grandfather, a contractor and building-supply owner, was looking for interior millwork to complete his home in Florence, S.C. He was in a hurry, Mitchell Powell says, “so he bought the company and brought it here in 1957.”

A mantel with hand-applied decoration represents hours of work.

In the 1950s, Driwood offered fewer than 50 mouldings. Now there are more than 500 in stock, and the company makes custom millwork to order. Many of the moulders on the shop floor are vintage, including a push-feed moulder made by S.A. Woods Machine Co. in the early 1930s. But the most interesting machine is a vintage embosser: “That machine is very old. It’s got a patent date of 1870-something stamped on it.”

Examples of embossed mouldings, made using pressure and heat.

The embosser turns out mouldings that are near-replicas of hand-carved trim, from egg-and-dart bed moulding to bolection-faced chair rail with an inverted acanthus-leaf pattern. For each pass, the embosser is fitted with a die, a bronze wheel with a patterned surface that impresses the pattern on wood using heat and pressure. Simpler designs may make one pass through the embosser, while more ornate ones go through up to four times.

A workman feeds wood into the planer as it cuts curved mouldings.

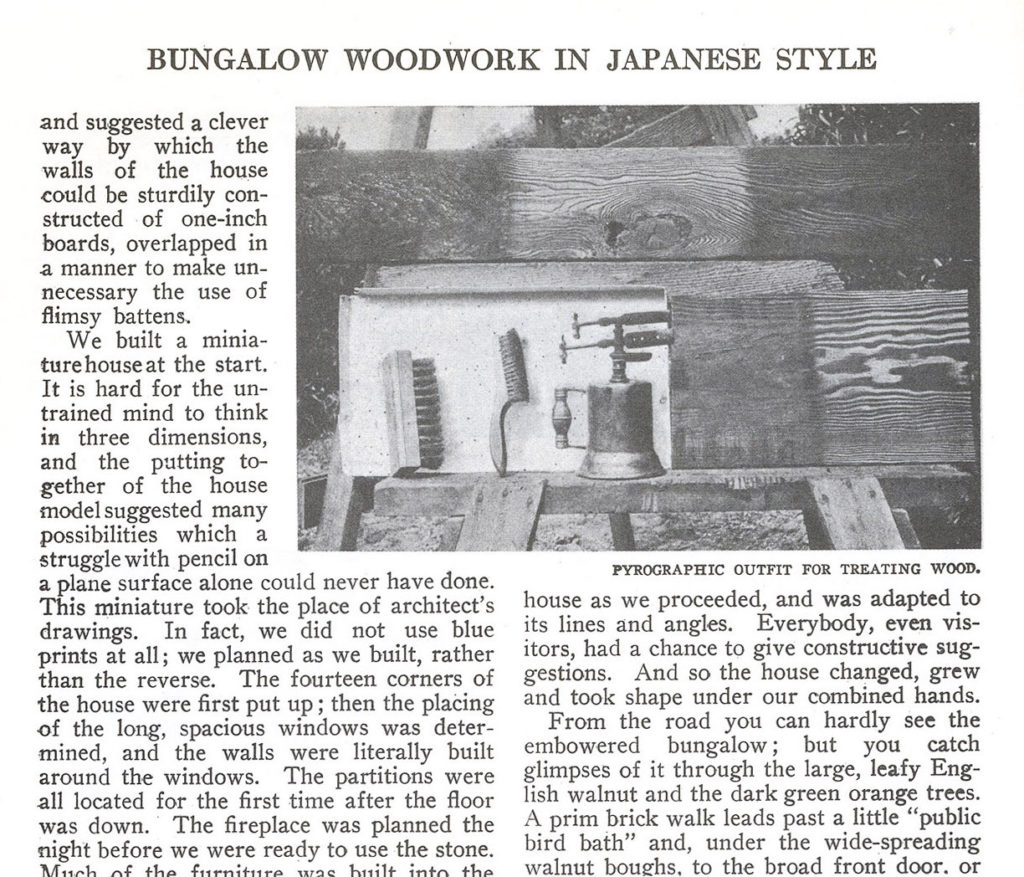

The die is first heated with a propane torch before the millwork is fed through. It is then rotated by hand, with the operator making subtle adjustments depending on the design and the type of wood. “You have to adjust the heat or the pressure to get it to create the design perfectly,” Powell explains.

About half of Driwood’s work is new construction, while fully 50 percent is restoration. For whole-room or whole-house installs, the company almost always sits down with the customer or architect and re-draws the submitted plans. That’s because most clients aren’t skilled in the art of classical proportion. “When it comes down to the proportions of a cornice . . .

even architects aren’t trained to understand that anymore. Every bit of what we do requires human interaction at each step.”

Pro Tip: Quirked bead or bead and quirk, familiar from beadboard, was a common flourish in millwork before 1900, appearing on trim including door and window casings. (The quirk is the groove that separates the rounded bead from the rest of the surface.) Quirked beads show up in many styles of architecture, from Greek Revival to Late Victorian.