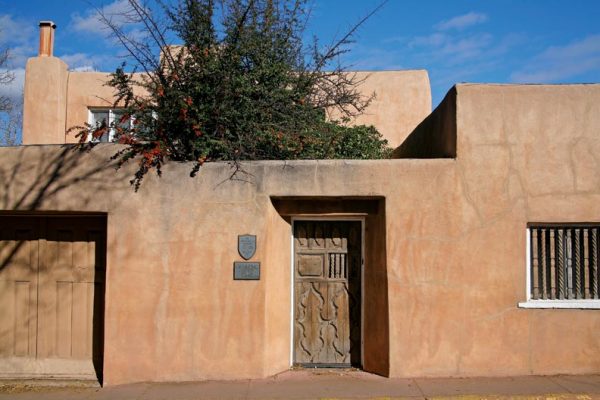

Strong geometric forms with a typical carved-wood door mark the 1923 Edward Brooks House.

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, where Native American, Spanish, and Anglo cultures meet and blend as seamlessly as the earth-toned features of its ancient high-desert landscape, the old is always fashionable.

A hundred years or so ago, some of Santa Fe’s savviest business and political leaders decided to embrace their small and struggling territorial capital’s past by promoting an official architecture for the town. They called it “Old-New Santa Fe Style.” Picturesque adobe buildings—new or old—combined with stunning scenery, wonderful weather, and a uniquely New Mexican slant on life made Santa Fe irresistible to artists, writers, and their wealthy patrons—not to mention Eastern tourists heading west on the new transcontinental Santa Fe Railroad. The juxtaposition of the early 20th-century Arts & Crafts movement, which emphasized regional and indigenous history and culture, also bolstered interest.

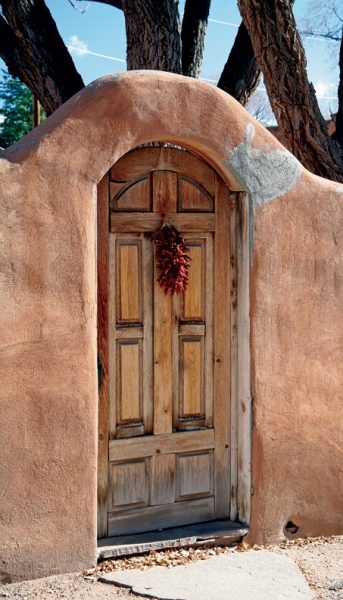

Entrance doors in adobe surrounds are a core Santa Fe Style tradition.

Before long, the newly popular “Santa Fe Style” tightened into what amounted to unwritten policy (codified in 1957 with a historic district ordinance that required the use of “Old Santa Fe Style” for new construction). Even large Queen Anne-style houses were sometimes “pueblo-ized” with a coat or two of stucco over their original façades. Today, a century after New Mexico gained full statehood, the town fathers’ decision remains in play, resulting in a city dominated by Pueblo Revival, Spanish Revival, and Territorial Revival buildings—the new “Old-New Santa Fe Style.”

Native Culture

The term “pueblo” (Spanish for “people”) refers to a village, the people who live in it, and the culture they create. Pueblo Revival houses are usually one (occasionally two) stories in height, and generally horizontal in line and asymmetrical in shape. They are characterized by invisible flat roofs supported by vigas, wooden-pole beams that project through the walls. The roofs are drained by canales, trough-like wood or (more frequent today) metal channels that also project from exterior walls. Thick plastered walls have gently rounded corners, sometimes hugged by adobe buttresses.

Decoration is scant, confined mostly to blue- or red-painted wood trim at windows and doorways. Portales—long, narrow covered porches, generally with flat roofs and log posts—are customary, though not mandatory, on the fronts or sides of Pueblo Revival houses, providing shelter from the relentless desert sun. Entrance doors may be single or double, usually of vertical-board construction.

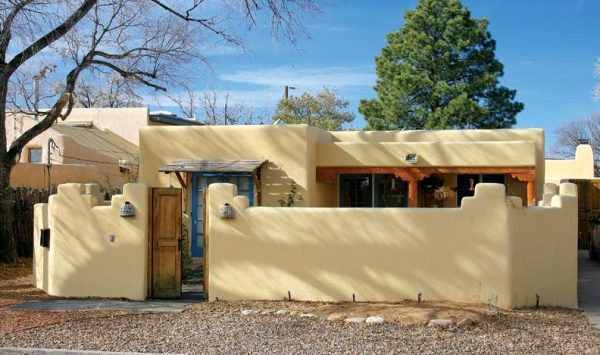

A classic 1950s developer’s Pueblo Revival with the common steel casement windows and wide portale, or recessed front porch.

Windows in the oldest buildings were wood-sash casements. Steel casements were popular from the 1920s to the 1950s, while modern, updated windows more likely have aluminum or vinyl sash. New double-hung or horizontal-slider windows often replace casements altogether. Three-part picture windows aren’t uncommon in 1940s and ’50s houses.

Spanish Influence

Somewhat less frequently seen in Santa Fe, but still an important reminder of the city’s heritage, is the Spanish Revival or Mission style. Here again, stuccoed adobe is the building material of choice.

A porch with round arches on this 1940s house shows Spanish Revival influences.

Roofs are usually flat, but may have a slight pitch. Porch roofs and pent eaves over the windows may be covered with rounded barrel tiles, often of a highly visible red hue. The original Western ranch house and Spanish mission influences are evident in frequent round-arch openings in windows, doors, and arcaded porches (the inevitable portales). Asymmetrical massing supplies an extra measure of Arts & Crafts charm.

Territorial Ties

The final element in Santa Fe’s lexicon of historic styles is Territorial Revival. New Mexico was a territory from 1846, when the United States wrested it from Mexican ownership after the Mexican War, until 1912, when it was finally admitted to the union as our 47th state. The Territorial Revival style reveals the Anglo influence that appeared when the Yankees started moving to the inland west, bringing along a much-simplified version of Greek Revival style.

The late 19th-century Territorial Revival style introduced Anglo building practices such as the double-hung sash and signature brick coping on the roof edge seen here.

More symmetrical than either the Pueblo or Spanish Revivals, Territorial Revivals had a flat roof, like the Pueblo, but topped by a coping or rim of hard, dark brick that retarded weathering at the edges of its soft adobe walls. The walls also had crisper edges than those of Pueblo or Spanish Revival houses. Windows and doors were topped by slightly pitched wooden caps shaped like shallow inverted V’s.

The window openings in the first original Territorial houses contained double-hung wooden sash, but these houses reverted to the more “picturesque” casements hankered after by 20th-century revivalists. To be fair, casements may have been more practical, since they provided better ventilation in New Mexico’s hot, arid, and relatively bug-free climate.

Doors are of vertical-board or herringbone-patterned wood. Wooden trim around windows and porches, as well as doors, will most likely be painted the signature New Mexico turquoise or sky blue, though red and brown make occasional appearances.

Landscape Magic

Unabashed and skillful xeriscaping produces yards that, though often brown or gray, are surprisingly appealing as they abandon water-guzzling greenswards in favor of native plants and gravel. Front gardens are frequently softened and made private by adobe walls or screens made of unfinished wooden poles of varying heights and circumferences lashed tightly together. Nearly house-height adobe walls may be entered through heavy paneled and carved wooden gates or doors. Metal fences are rare, and so minimally decorated (perhaps with just a trace of rust) that they blend unobtrusively, like courteous houseguests, into the brown-and-gray background.

Walled front yards are a common Santa Fe feature, as in this 1950s example.

Above all, Santa Fe’s architectural magic seems to emanate from the textures and hues of the clay and lime that color its buildings—aged ivories, arroyo-mud browns, apricot and peachy pinks, sunny yellows, and bold ochres—washed by a brilliant sun emblazoned on the vast blue umbrella of a New Mexico sky. It’s a scene to bedazzle a nascent Georgia O’Keefe, D. H. Lawrence, or John Gaw Meem—or the next art collector, budding archeologist, historian, or scientist who opens the door of a Santa Fe art gallery or museum.