Mention tiles and most people envision those characterless bathroom coverings we all grew up with and continue to see too much of now. During the decades flanking 1900, though, tiles of a different sort grouted their way into many dimensions of American life, enlivening both public and private spaces with a sumptuous array of color and texture.

The Adamson House (1930) in Malibu, California, including the kitchen with its fanciful cooking alcove and wall clock, is a veritable showcase of tiles from nearby Malibu Potteries.

Tim Street-Porter

Companies such as Batchelder Tiles of Los Angeles, Rookwood Pottery of Cincinnati, American Encaustic Tiling of Zanesville (Ohio), and Grueby Faience of Boston took the tilemaking techniques of 18th-century Spain and fused them with the design ideals of Britain’s 19th-century Arts & Crafts Movement to produce a distinctively American look in useful clay—the art tile. Intended to be functional as well as attractive, art tiles were used architecturally in ways that have long been under-appreciated, but can still amaze and delight us today.

From Hearths to Berths

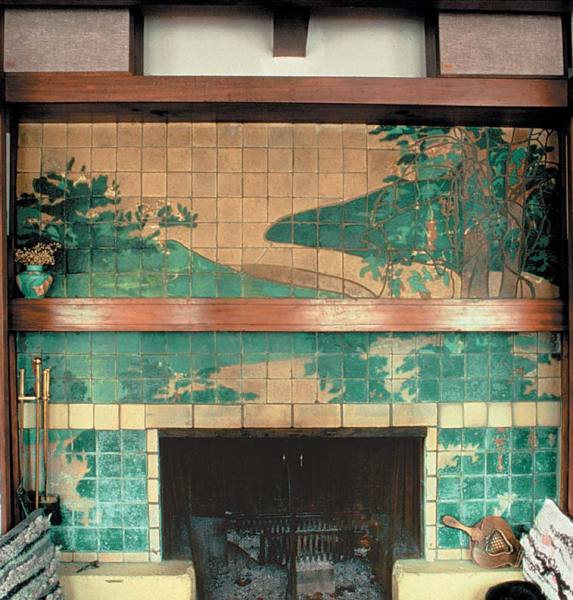

The tiles for this dining room fireplace in the Gamble House (1908) are known to be the work of Encaustic Tiling of Zanesville, Ohio. Charles Greene designed the mosaic insets using glass bits and iridescent ceramic shards.

OHJ Archives

Homeowners placed art tiles at the visual center of family life by setting them in hearths and mantels. Their matte glazes and peaceful, if often sentimental, subjects provided the perfect backdrop for rest, reading, contemplation, and conversation. Beyond the inglenook, art-tiled fireplaces could also be found in dining rooms, bedrooms, libraries, and home offices. Admittedly, an art-tiled fireplace was an objet de luxe and only the wealthiest could afford one. The least expensive fireplace surround with mantel shown in Rookwood‘s 1909 tile catalog—four simple molded decorative tiles set in a field of plain tiles—cost $50 at a time when the average American worker earned $5 a week. A fancy Rookwood fireplace with an overall design of lilies was equal to a year’s salary, even though it was made entirely of molded stock items, and Rookwood’s markup on tiles was only half of what it made on vases.

Art tile companies successfully snookered homeowners into believing that art tiles, despite their germ-grabbing matte glazes, were magically sanitary, even salubrious, so they are frequently found in “wet rooms”—kitchens, bathrooms, and nurseries. Rookwood’s 1925 tile catalog, the company’s last, begins with a full page of “Nursery Tiles in Matte Glaze Faience.” For the most part, the 31 designs offered are all sweetness and light: nice animals (bunny rabbits, ducks, geese, swans), scenes of Dutch windmills and canals, a castle at sunrise, belles with parasols and hoop skirts. Perhaps in a nod to the Gothic side of fairy tales, Rookwood’s nursery designs also included haunting, even scary, depictions of glowering owls, spiked brambles, and piscine monsters.

Elsewhere in the house, art tiles could be called on for wall panels, stair risers, and flooring accents. Specifically for wainscots, Rookwood designed a clever, modular cattail motif in eight 6″ x 8″ tiles forming a column of stalks and leaves that repeat. For visual interest the height of the cattails could be altered from column to column by using the bottommost tile twice (to make the cattail stalk taller) or omitting one or more bottom tiles (to make the stalk as short as two decorated tiles). This way, an architect equal to the design could generate endless variations around a room.

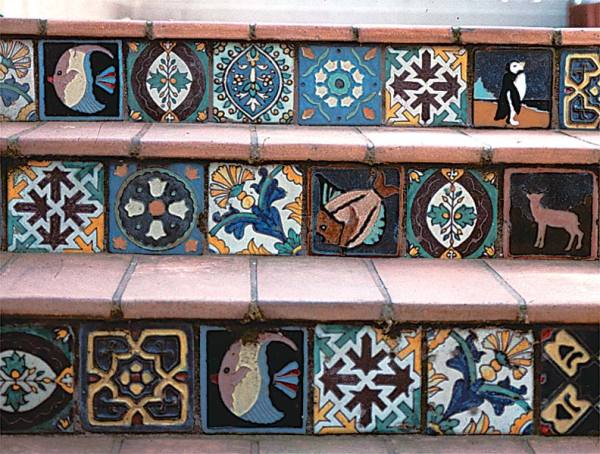

The tilesetter for these exterior stair risers in Oakland, California, has playfully pieced together a crazy quilt of tiles by the underrated company Solon & Schemmel of San Jose, California.

OHJ Archives

Particularly in California, art tiles were extensively employed as stair risers both indoors and out. Typically a single-tile repeating design would be used across each riser, but rarely was one design used for all the risers. Usually each riser had its own design, or the tile setter established a rhythm for the staircase by having three or four designs repeat up the risers by turns. Using tiles as risers rather than treads helped guard the decorated surfaces from scuffs and dings, while adding visual pep to an architectural detail that normally goes unnoticed.

In the 1950s film classic Sunset Boulevard, Norma Desmond reports that her palazzo guest Rudolph Valentino claimed, “It takes tiles to tango.” In reality the glazes on art tiles could not be fired hard enough to resist the gradual abrasion wrought by a million swirling heels, and no tile is immune to scratches etched by a stone caught in a Vibram sole. Nonetheless, architects frequently disregarded these limitations and specified even high-glaze tiles as flooring. Tilemakers themselves were equally cavalier, producing whole lines of decorated accent tiles for use on floors. Their solution was to place glaze only in deep recesses, leaving the exposed, higher-fired clay body to suffer schlepped-in grit. In 1914, William Grueby attempted to revive his flagging, already once bankrupt tile business by producing such floor tiles almost exclusively. He poured a single glaze (usually mustard brown) into the recessed background around a red clay foreground design of a cupid, mermaid, monk with cello, knight, or the like.

Out of doors, art tiles could be found cladding benches, forming fountain spouts and basins, ringing swimming pools, and even, in the case of Frank Lloyd Wright‘s 1924 Ennis House, serving as accents in a scored, poured concrete driveway. Two of Wright’s Prairie School colleagues, Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony, sometimes used decorative arrays of art tiles set right into the sides of the houses they designed.

Ceramics in Commerce

Architect Marion Mahony complemented her design of the Robert Mueller House (1910) in Decatur, Illinois, with a mosaic of glass and tile elements.

OHJ Archives

Outside the home, America entrusted the physical, moral, and intellectual development of its children to schools, orphanages, libraries, health-care facilities, and even sports stadiums decorated with art tiles. In Ocean Springs, Mississippi, the entryway to the 1930s grade school (now a school district office) is flanked by site-specific Work Projects Administration tile installations from the town’s Shearwater Pottery (1928-present). The barrel vaults of the Cass Gilbert-designed loggia for Oberlin College’s art museum (1917) are covered in a mosaic of tile tessera by Pewabic Pottery of Detroit.

Through the luck of renovative inertia, a surprising number of school buildings retain their art-tiled drinking-fountain alcoves, even when their original bubblers have been replaced by throbbing refrigeration units. The Children’s Reading Room at the Detroit Public Library (1921) has a huge fireplace, the surround for which is a series of 10 classic children’s stories rendered on tile plaques by Pewabic Pottery. In Boston, the walls of the Forsyth Dental Infirmary for Children (1912), now the Forsyth Dental Center, are studded with thousands of decorated nursery tiles by the local potteries, Grueby Faience and Saturday Evening Girls (1908-42), and Doylestown, Pennsylvania’s, Moravian Pottery & Tile Works (1899-1954).

This satyr-turned-fountain is by Solon & Schemmel (later Solon & Larkin). Referred to as “S&S,” the regionally focused company produced tiles for the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park and the kitchen at William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon.

OHJ Archives

Even folks of meager means could experience site-specific installations by America’s greatest tile companies simply by riding the New York City subway. The stations of the original 1904 line are decorated with Grueby Faience plaques thematically keyed to each stop: the Nièa, Pinta, and Santa Maria grace the Columbus Circle station while tile beavers chew tile stumps at Astor Place. The 1905 extension features Rookwood tiles depicting—surprise!—a Fulton steamer at the Fulton Street Station.

The use of art tiles was no less common at other transportation centers, especially railway stations. At New York City’s Grand Central Terminal (1903-10), the Gothic grilles over the train platform entrances are by Rookwood. Short-lived California China Products (1911-17) produced tiles for a whole chain of Santa Fe Railway stations running through the Southwest, culminating in the dazzling domed terminal in San Diego (1915). In Los Angeles, cavernous Union Station (1939) is unified and humanized by the tile wainscoting made by Gladding-McBean (Los Angeles and Lincoln, California) that uses earthen tones and smooth-cornered chevrons to generate a unique Deco Southwest look. Cincinnati’s Union Terminal contains Rookwood’s last-known tile installation (1931-33), a tea room, now ice-cream parlor, that is a tile jewel box—wacky pastel flowers and insects all blooming and buzzing against fields of mauve, mint green, and pale grey.

Americans conducted their civic rituals in buildings that used tiles to help convey a sense of stateliness and monumentality. Golden tiles by California Clay Products of Los Angeles crown San Antonio’s Municipal Auditorium (mid-1920s). Los Angeles City Hall (1928) has literally thousands of square yards of Malibu tiles marshaled into 23 multistoreyed panels in its awe-invoking lobby, stairwells, and council chambers.

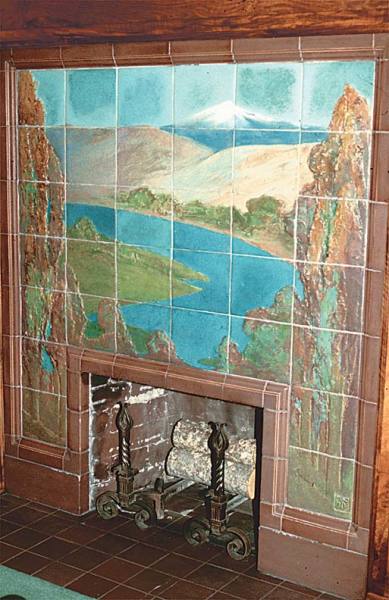

The Great Hall fireplace at Seattle’s Leary Mansion depicts regional scenery—probably the Columbia River and Mt. Adams.

Melissa Rosengard/Courtesy of Diocese of Olympia

Perhaps the most impressive tile installation in a governmental setting is a jaw-dropping faux-Mayan design by Enfield Pottery that fills every inch of the vestibule to the annex behind the Organization of American States headquarters (1912) in Washington, D.C. Banks and office buildings used tiles to create imposing but welcoming exteriors while providing attractive, low-maintenance claddings for foyers, lobbies, and elevator halls. A veritable gulch of tiles, Fourth Street in Cincinnati is flanked by a series of tiled façades—Carew Tower, Gidding-Jenny, Dixie Terminal—by the city’s Wheatley and Rookwood potteries. Some motion picture theaters incorporated art tiles as well—Rookwood at Washington, D.C.’s, Chase Theatre (1917), Solon & Schemmel (San Jose) at San Francisco’s Castro Theatre (1922), Malibu at Los Angeles’ Mayan (1927), and Gladding-McBean at Oakland’s Paramount (1930).

Regrettably, much of America’s tile heritage has slipped from consciousness with the swing of the wrecker’s ball. Of all tiled structures, restaurants seem to have been the most often hit. This loss is particularly sad because restaurants were frequently large-scale total tile environments–that is, sites where all surfaces, trims, floors, columns, and ceilings (usually vaulted) were executed in decorated tiles presenting a unified theme or scene. Fortunately, tiled churches and cathedrals have fared somewhat better. The best-known such site is the 1911 installation of Grueby tiles as flooring in New York’s St. John the Divine. Tile companies loved to produce tiles in thematic series (like the signs of the zodiac or the four seasons) so, not surprisingly, the most common ecclesiastical design were the four Evangelists. As with restaurants, church architecture provided opportunities for total tile environments. Such is the network of groin arches that make up the glistening Crypt Church of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. (1922-26), which is sheathed with earth-toned and iridescent Pewabic tiles.

New Century Tile

Art-tile production never wholly passed from the American scene. True, the Depression wiped out the majority of the original shops and World War II many more, but even as the last of the pre-Depression art-tile companies sputtered to a close in the 1950s and early ’60s, other modes of art-tile production had already taken off. By the Depression, national companies such as Prang Art Supply and American Art Clay Company were pushing tilemaking in schools, and these companies are still in business. (In fact, art tiles were being made in schools as early as 1910.) By the early 1950s, designer Harris Strong had a shop in the Bronx producing art-tile plaques to serve as guest-room decor for motels along the Pennsylvania Turnpike. He too is still active.

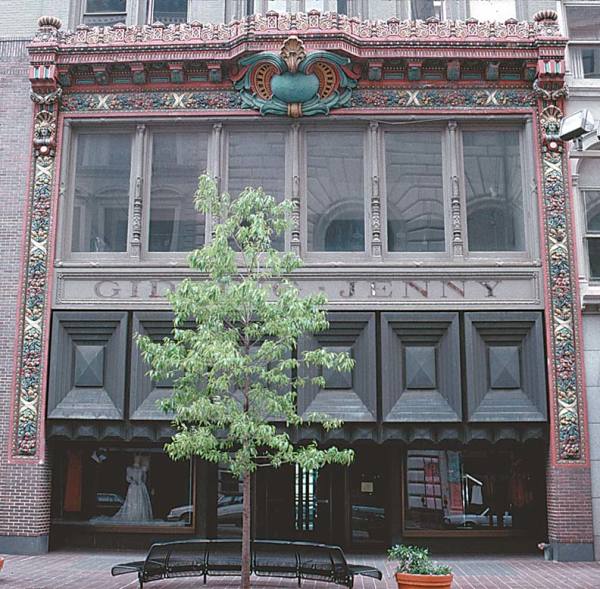

In 1920, this Italianate tile façade by Rookwood Pottery was added to the Gidding-Jenny clothing store in Cincinnati. Its theme—autumnal harvest—is represented by grapes ready for pressing, gourds ready for drying, and pomegranates ripe to bursting.

OHJ Archives

More than the ever-growing revival of the Arts & Crafts movement, postmodernism’s embrace of color, texture, decoration, historical referencing, and…well…fun have made this design philosophy the perfect vehicle for the return of tile and decorative terra cotta to architecture. New York has added new tile installations to its subway system. In a bold extension of San Antonio’s great tile tradition, the nine-story façade of the city’s Santa Rosa Children’s Hospital (1997) is one giant tile mosaic mural. The foremost American architect to use tile is Robert (Learning from Las Vegas) Venturi. His 1991 Seattle Art Museum incorporates tile and decorative terra cotta across the first-floor façade to give the building a visual fillip without being outlandish or merely cute. With this sort of imprimatur, we can expect to see still more great applications of art tiles in America. While the titans of architecture absorb Venturi’s work, wouldn’t your kitchen benefit from some matte glazes?