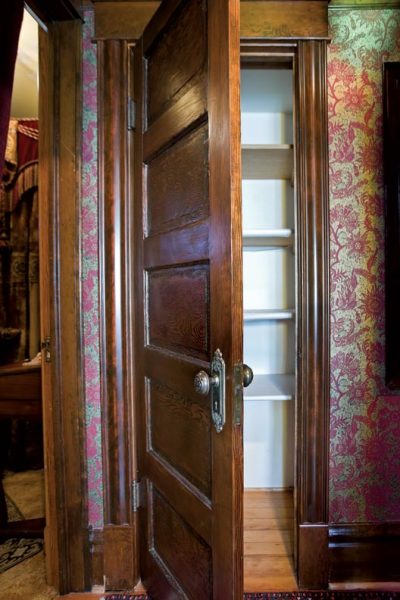

The new cabinet was built into the space once occupied by a hall closet added in the ‘70s.

Photos by William Wright

My hall linen closet was an eyesore. My turn-of-the-century house had good bones and detailing, including aged fir woodwork and trim that had never been painted, and had mellowed to a golden amber. But the previous owners had “updated” the upstairs hall in the ’70s, carving a linen closet from space under the eaves in an adjacent bedroom. Done on the cheap, it had flimsy particleboard shelves lined with flowery vinyl paper. Every time I opened the door, all I could do was sigh.

Then I visited a spacious Craftsman with a generous linen press built into its upper hall landing. Immediately, I knew this was the answer. The Craftsman closet’s construction was simple: plain upper cabinets and wide, spacious drawers underneath, large enough for bed linens and towels. A shallow shelf projected several inches out, dividing the upper cabinets and lower shelves—a handy spot for resting a laundry basket or folding a stray towel. Made of fir, the cabinet blended in perfectly with the rest of the home’s woodwork: a handsome built-in typical of the practical Arts & Crafts home.

By Design

The old closet had flimsy shelves covered with vinyl paper.

In order to make my own linen closet look like it had been there all along, I knew the key would be to find old fir compatible with the rest of the home’s woodwork. My builder, Jim Docherty, scoured the local salvage yards and turned up enough turn-of-the-century fir to construct simple drawer fronts, upper cabinets, and shelves.

I was lucky enough to have an original built-in breakfront in the dining room, and we used its straightforward design as our template: flat cabinet doors relieved by a simple 3⁄8″ raised border and unadorned drawers with a single front panel. We used only the salvaged fir throughout for strength and consistency—no plywood allowed!

Jim built the upper cabinet doors with flat fir panels and mortise-and-tenon stiles and rails. Each door was 36″ tall by 11″ wide with 1½” stiles, a 2″ top rail, and a slightly wider 3″ bottom rail that helps visually anchor the door’s frame. The center panels were made of solid fir; Jim installed the thick raised panels backwards to achieve a Shaker-style flat front while also preventing splitting as heat and humidity took their toll. The doors were installed flush to the frame with simple brass ball-top hinges for a touch of period simplicity.

With an eye to longevity, carpenter Jim Docherty used only salvaged fir for the cabinet’s construction, even for framing.

To further echo the dining-room breakfront, Jim fitted vintage fir beadboard paneling across the inside of the upper cabinet. Two 36″ x 16″ fixed shelves were installed; each was finished with a ¼” raised, beaded edge to tie into the paneling, as well as to prevent linens from sliding off.

As a finishing touch, Jim lined the interior of the upper cabinet with fir beadboard, a nod to the breakfront that inspired it.

The three 24″ x 20″ lower drawers are each deep enough to allow plenty of room for towels and sheets. They are graduated from top to bottom—the top drawer is 7½” tall, the middle drawer is slightly taller (9″) for larger-sized linens, and the bottom drawer is the largest (10″) for storing blankets, mattress pads, or other bulky items. (The idea for graduated drawer sizes also came from the dining-room breakfront.) Jim made drawer guides from wooden strips, undermounted—like those in the breakfront—with ¾” x 1½” dovetail slides down the bottom center of each drawer.

Finishing Touches

To make sure the linen press looked like it had been part of the home’s original construction, the finish was crucial. Jim first stained the wood with an aniline dye, then brushed it with two coats of oil stain to match the mellow reddish gold of the aged fir trim in the rest of the house. A final coat of Zar water-based sealer in a satin finish added a subtle, hand-brushed sheen.

I’m always collecting interesting knobs and hardware at flea markets and salvage stores (you never know when you’ll need something), so I dug through my boxes to finish off the cabinet. I came up with a pair of Low Art Tile knobs for the upper cabinets and a set of circa-1900 bronze pulls in the shape of hands for the lower drawers. Perhaps they’re not what would have been used originally, but they are of the period—and a subtle nod to my eccentric tastes.

The author raided his collection of vintage hardware for knobs to adorn the new linen press, including these cameos from Low Art Tile.

When I look at the linen press now, I often wonder how I went so long without one—although I admit the sock drawer already needs sorting out.

Brian Colemanis a Seattle psychiatrist whose love of old houses led him to a second career as an author of books and articles on the decorative arts.