A quintessential Colonial Revival entrance hall is complete with a raised-panel wainscot and bold moldings. (Photo: Steve Rosenthal)

Before the age of gypsum and drywall, interior plaster walls were vulnerable to all sorts of potential damage. Hence the paneled wall, and the wainscot—a protective and decorative covering for the lower third (or so) of the wall. Early wainscots were always wood, but later innovations would introduce many alternatives.

A wainscot beneath the chair rail is a treatment that goes back to colonial times. Yet wainscots were secondary to the main event: floor-to-ceiling wall paneling, the method of choice for protecting walls for more than two centuries. Usually found in the main room of early colonial homes, the oldest wall panels were rough or hand-planed boards or planks. Entire rooms were paneled. If paneling was applied to only one elevation, invariably it was the fireplace wall, where paneling served as an extended surround and a handy place to conceal niches or shallow cabinets.

Raised-panel walls didn’t become fashionable until about 1750 or so, when builders of finer homes began incorporating details in the Georgian style, lifted from English pattern books. Far more sophisticated than plank paneling, raised panels can be configured to create focal points around architectural elements: fireplace openings, doors, windows. When panels are combined in a sophisticated, balanced design, the room takes on added dimension and looks “finished” in the same way that a piece of good furniture does. Raised paneling was popular in entry foyers, staircases, and receiving rooms like parlors.

An otherwise plain wainscot embellished with molding and pilasters in an 1803 Federal. (Photo: Gridley + Graves)

Wainscoting Styles

Formal raised-panel wainscot consists of a floating wood panel with beveled edges, held between vertical stiles and horizontal rails. Beveling the panel’s edges creates a three-dimensional surface. A variation, the flat-panel wainscot, is probably a Shaker invention. Today, modular paneling systems create the look without the labor. These new materials are made of dimensionally stable composites of wood or resin.

Georgian decoration lasted in America until the end of the 18th century, when the more restrained decoration of the Adam style began to take hold. The new style dictated that wall paneling recede to a low wainscot height, with the greatest expanse of wall to be covered with wallpaper.

Since the Victorian era, milled beadboard has been a low-cost alternative to fancier wall cladding. Beaded boards are relatively thin pieces of tongue-and-groove lumber with a side bead or convex molding along one interlocking edge. (The bead is a device to distract the eye from gaps that form as the wood shrinks and swells seasonally.)

Once a cheap and practical wall covering considered fit only for back-hall and service areas, beadboard now appears front and center in many high-end bathrooms and kitchens. (Photo: Gross & Daley)

Today, inexpensive “beadboard” paneling is churned out in materials from medium density fiberboard (MDF) to vinyl, but 300 years ago, the thin bead along the vertical edge of each board was hand-tooled by a joiner. Inexpensive even when machine-cut from Southern pine and cypress, beadboard was ubiquitous in back-of-the-house rooms frequented by servants, like the kitchen and utility areas. Beadboard is standard for porch ceilings; in seasonal cottages, the entire house might be paneled in beadboard. It can be run vertically or horizontally, used as a high or low wainscot or sparingly as an accent, or may cover the walls and ceiling of an entire room.

For many, wood paneling and related wall treatments are the ne plus ultra of the Arts & Crafts home. As Gustav Stickley wrote a century ago, “no other treatment of the walls gives such a sense of friendliness, mellowness, and permanence as does a generous quantity of woodwork.”

Walls in this era were often wood-paneled to chair-rail or plate-rail height. Woodwork might be golden oak or oak brown-stained to simulate old English woodwork, or stained dull black or bronze-green. (Painted softwood was also becoming popular, especially for bedrooms, with white enamel common before 1910 and stronger color gaining popularity during the ’20s.)

A classic Arts & Crafts skeleton wainscot. (Photo: Douglas Keister)

Board-and-batten paneling is fairly simple to install. Wide (12″) planks of oak, fir, red gum, or cypress are butted together vertically; the joints are covered with narrow battens (2½”- to 4″-wide strips of wood). Topped with a molded plate rail, this installation was a straightforward means of creating the look of expensive 3-D paneling.

Variations on the board-and-batten theme include what was called “skeleton wainscot,” where panels between the battens were not wood but rather covered in leather, faux leathers, embossed wall coverings including Lincrusta and Anaglypta, and the less expensive classic, burlap.

The last great fad in wall paneling was, of course, knotty pine. An inexpensive cladding material (the knots made it unsuitable for structural use), knotty pine, complete with its woodsy scent, conjured up the log cabin of our national nostalgia. How it became popular for postwar suburban homes is a bit of a mystery.

Decorative Walls

Painted, papered, and textured finishes often were used in combination with a wood wainscot.

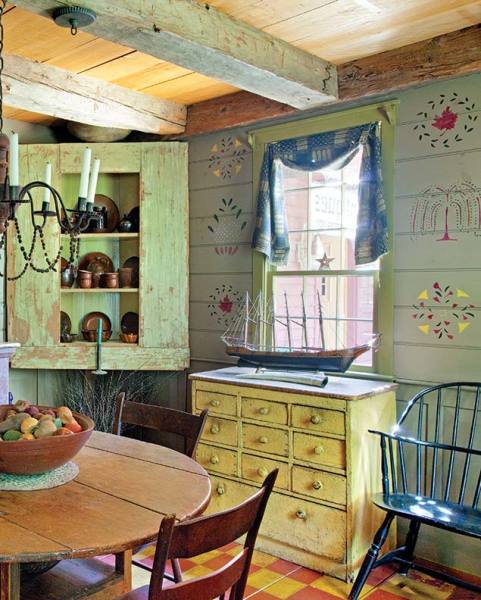

Stencil-painted motifs on board walls in the manner of the late 18th century, in a replicagambrel house in Maine. (Photo: Eric Roth)

Early homes: The plaster wall above might be papered or stenciled. Wallpaper was widely used during the early 19th century, often above a wainscot—or above a decorated dado. (Dado refers to the section of wall below the chair rail, and it has not always been clad in wood.)

Victorian: High Victorian rooms, formal and with high ceilings, demanded treatments that began at the baseboard and rose to the ceiling like a classical entablature. By then, custom wood paneling had become too expensive for all but the wealthiest homeowners, so other materials were used to create the dado or wainscot. Looking for ways to expand the market for linoleum, Frederick Walton created Lincrusta, a linoleum-based embossed wallcovering, in 1883. A less expensive, embossed cotton rag-based paper, Anaglypta, soon followed. Embossed papers were ubiquitous as treatments for the dado. Competing treatments included real and imitation embossed leathers and textured fabrics, including grasscloth.

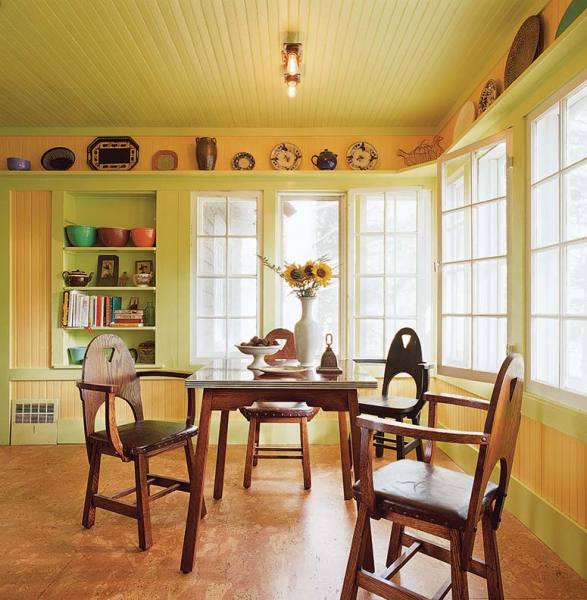

Swedish, English, and American Arts & Crafts influences show in this wainscot and plate rail. (Photo: Carolyn Bates)

Arts & Crafts: This early 20th-century era brought back the high wainscot. Gustav Stickley himself recommended leather as both rich and unobtrusive for use in battened or skeleton wainscots. Burlap panels constitute an authentic bungalow wall treatment, one that is easy and inexpensive to re-create. A century ago, the burlap applied to such walls was paper-backed; modern substitutes include dense, tightly woven fabrics with a significant linen content, such as linen union or bungalow cloth. Several wallpaper makers offer a faux burlap paper. The frieze is a decorative border that trims the area right below the ceiling. In the early 20th century, frieze depths ranged from as little as 8″ to 16″ or even considerably more.

See resources for this story here.