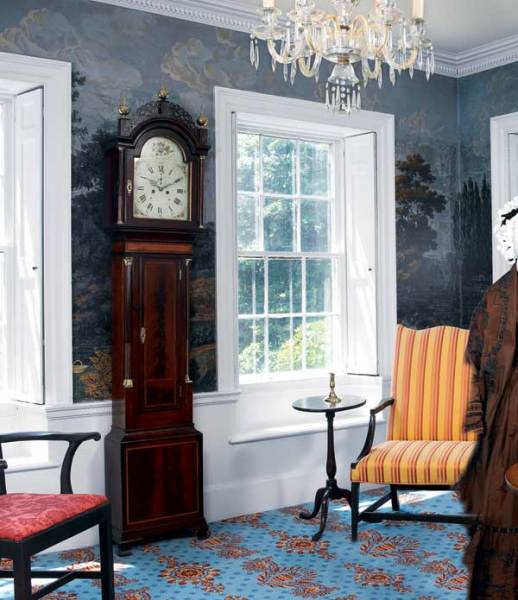

In high-style Georgian homes, raised-panel shutters often reflected floor-to-ceiling room paneling, like these reproductions from Americana.

Before windows were treated to a dimity swag or scrim of muslin—before even glass—interior shutters met the basic requirements for protection from the elements. Practical, versatile, and visually appealing, interior shutters have retained their popularity over time, making them an appropriate choice for a large variety of period rooms.

Like the homes for which they were built, the earliest shutters were very basic: a single panel on a track, or grooved rail, that ran along the surface of the wall and the base of the window. A second type, consisting of one or two shutters, was vertically hinged. When opened, it was folded to the side of the window against the wall. The problem with both these styles was that they ate up precious space. Gradually a more practical design evolved: single or paired shutters that slid into cavities built into the plaster walls. At the time these were known as pocket shutters or privacy shutters. Another name lingers: “Indian” shutters, though this moniker originated in 19th-century New England, when folks began to mythologize the original function of pocket shutters as protection against “Indian raids.”

Paired folding panel shutters in the Gardner–Pingree House in Salem, Massachusetts, can be opened at the top or bottom for full or partial light. (Photo: Courtesy of J.R. Burrows & Co.)

By the 18th century, interior walls were being brought further into the room. The window embrasure, or opening, became more deeply recessed. This recess provided a convenient place to store shutters when not closed, but it also provided new options for interior woodwork. Carpenters rose to the occasion, fashioning handsome panels that took shutters beyond the merely functional. These shutters could be single hung or double hung—the latter allowing the top and bottom halves to hinge open independently, bringing in light but retaining privacy.

While raised panel shutters were ideal for the North with its colder climes, Southern homes had different needs. By the late 18th century, the louvered shutter had gained the upper hand in popularity down South. The center slat that allowed the shutters to open and close made it possible to deflect the blistering sun while still providing ventilation. These plantation shutters, as they came to be called, were aesthetically appealing as well: their wider slats gave rooms a lighter, airier feel.

Many companies today continue to manufacture interior shutters, offering a wide selection of styles and configurations, as well as custom options such as Palladian designs. Raised-panel shutters are often designated “traditional” or “Colonial,” and louvered shutters “plantation.”

Recessed, raised-panel shutters are original at a Federal-era mansion in Duxbury, Massachusetts. (Photo: Greg Premru)

Shutters are constructed of hardwoods, which are exempt from the danger of a sap bleed, unlike softwoods. Cedar is often used, but most shutters are constructed of lightweight and stable domestic basswood and poplar. In addition, a handful of companies offer a selection of custom hardwoods. Shutters of engineered wood and acrylic that mimic real wood are also readily available.

Interior shutters can be painted or stained, depending on your preference. Some shutter-makers can match the stain on your existing millwork or provide advice on a finish that will correspond with your interior décor.

Today’s interior shutters are generally mounted in two ways. Most common, because it is simplest, is a frame mount in which the panels are attached to a thin frame on the window casing or adjoining wall. This method avoids issues caused by out-of-square old windows. More closely following historic precedent is the inside mount method, in which the panels are attached to wooden strips on the window jamb itself.

Raised-panel shutters fold back into deep window recesses at Drayton Hall, an 18th-century mansion in Charleston, South Carolina.

A final option is available to people who have built-in bookcases or cabinetry on either side of their windows; a few companies are able to use the cabinetry depth to mimic the window jamb, creating the look of an embrasured window. All shutter manufacturers offer online guidelines for measuring, and most have people available to walk you through the process by telephone as well.

When making a decision on what shutter type is best for your home, take time to thoroughly investigate each company’s website. Some are committed to providing traditional methods of joinery, using premium woods. Others recognize that their customers may not have unlimited budgets or that they may have concerns with the longevity of a real wood blind in particular climates. If you are considering louvered shutters, be sure to compare the size of the louvers (historically these were of generous dimensions) and consider what effect this will have on the appearance of the shutters, and the look of your period room.

For shutter sources, see the Products & Services Directory.