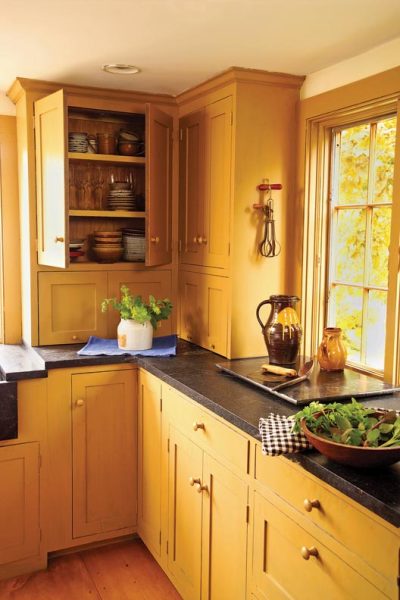

Soapstone is a time-honored kitchen accompaniment that also holds up to heat, water, and stains. Integrated soapstone sinks have a long history in New England. (Photo: Eric Roth)

The built-in kitchen countertop is largely a 20th-century phenomenon. Wood, marble, and the occasional metal counters usually appeared only in the pantry, even in the most stylish 19th-century homes. When it was present, the worktop was usually a dry sink or a wood table, both of which endure as inspiration for the vintage-look counters we prefer today.

Stone is probably the oldest work surface. (Think grinding grain on stone, and you’ve got an idea of about how long it’s been in use). Soapstone and slate have been quarried in the Northeast for at least 150 years and have been used as both dry and wet sinks for at least that long.

Soapstone, the original lab countertop, is extremely durable, nonporous, noncombustible, and won’t interact with chemicals or acids like lemon juice. Over time, it oxidizes from light gray or green to charcoal or dark green. Like other stones, soapstone can be polished to a shine or honed to a traditional matte finish.

Marble is a softer stone that pits and stains easily, but remains a time-honored choice for pantry countertops. (Photo: Sandy Agrafiotis)

Most imported slate is too soft for countertops, but not the fine-grained schist from New York, Maine, and Vermont. Dense and nonporous, slate resists stains and etching from acids like wine and fruit juices; as an added benefit, it doesn’t need a sealer. In the early 20th century, slate laundry sinks were so common you could buy one from a plumbing catalog. It comes in beautiful colors: light gray to charcoal, light to dark purple, light and medium green, soft red, plus purple-streaked greens and grays.

Another traditional stone making a comeback in the kitchen is marble, but because it’s porous, and stains, etches, and pits easily, it’s more appropriately used in backsplashes, as a pantry counter (as was common in the 19th century), or as an inset for rolling out dough. If you want the look of marble without the maintenance issues, consider a manmade quartz blend.

Ubiquitous in kitchens for more than 20 years, granite remains a versatile option because the choices, colors, and patterns are so diverse. Many granites are nonporous, an advantage over traditional soapstone or marble. Light granites can stand in for marble; grays and blacks offer the look of traditional stones with less maintenance. Hone it for a subtler look more in keeping with many old-house styles.

While not a traditional material, granite’s durability and range of colors work well in historic kitchens. (Photo: Blackstone Edge Studios)

5 Tips for Timeless Counters

1. Mix and match. Choose wood for a dry prep or pantry area, marble for rolling out dough, and stone or a manmade surface for wet/

hot areas.2. Play up the details. Finish counters with traditional edge profiles (ogee, bullnose) or—in mid-century kitchens—metal trim; add drainboard grooves to wood, stone, quartz blends, or even concrete.

3. Consider an integral sink or a backsplash made of the same material as the counter. You’ll get a sleek look that’s both of the moment and timeless—as well as easy care.

4. Buy locally sourced stone. Soapstone, slate, and area-specific stones have been mined in the Appalachians from Virginia to Maine for more than 150 years; limestone, marble, and granite are quarried in the Midwest (especially Indiana). Not only are these materials green, they are historically authentic.

5. Coordinate the textural style and colors in the stone with those of cabinets, wood trim, and backsplashes. For example, pull out a darker tone from a light stone countertop for the tile backsplash and another for the cabinets.

An early option, wooden counters are often found in the original pantries of less formal houses. (Photo: Ken Lay)

Wood has long had a presence in both kitchen and pantry: Pine, maple, and oak were top choices for worktops at the turn of the 20th century, but butcher block was the most popular wood countertop. Butcher block counters or islands are formed from strips of hard maple or oak bonded together with the grain edge facing up for stability. Many high-end wood countertops are offered with long-lived (and even minimal-maintenance) permanent finishes, but wood intended as a cutting surface is usually finished with tung or mineral oil. Because wood can burn and will turn black with repeated exposure to water, it’s best used away from the stove or sink—topping for an island or pantry, for instance.

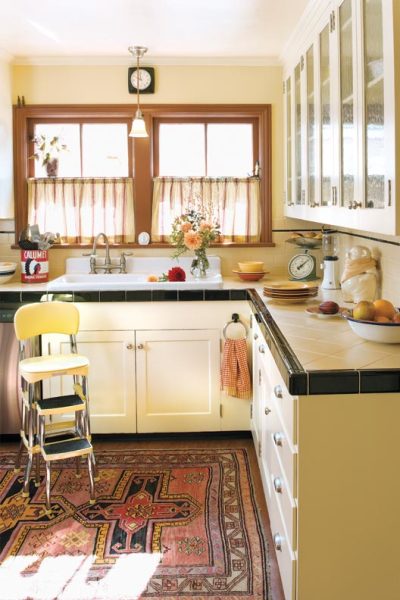

Tile first appeared in kitchens in the late 19th century, as the “sanitary” movement began to sweep the country. Clean white 3×6 subway tiles and 3″ or 4″ squares were standard on both counters and backsplashes. Grout joints were kept deliberately thin, no doubt to diminish opportunities for encroaching dirt. In the 1910s, many counters were trimmed with bullnose caps in contrasting colors like black and green. By the late 1920s, countertops grew colorful with oversized hexagons in olive green, bisque, black, and pale yellow.

Ceramic tiles were popular from the 1920-40s, like this 6×6 example laid on the diagonal and trimmed with black bullnose edging. (Photo: William Wright)

Stainless steel, nickel, and other metals have been in widespread use since the 1920s (and appeared even earlier in ads in magazines like House Beautiful). Stainless steel was especially hot in the 1940s and ’50s, sometimes used for cabinets, too. As the name implies, it won’t stain, lasts practically forever, and is easy to clean.

It may come as a surprise, but the first laminates were patented in 1909. (Formica celebrated its centennial in 2013.) Because they were novel and expensive, laminates didn’t catch on as surfacing materials until the 1920s (on radios) and ’30s (in diners and movie theaters). After World War II, the market for laminate countertops exploded, offering homeowners a dizzying array of colors and patterns. Though Formica still comes in a vast number of designs, a few mid-century patterns offer the most authentic choices for restoration.

Whatever work surfaces you choose for your kitchen, aim for materials that suit the style of your house and the era when it was built. The older the house, the more sensitivity required. Luckily for those of us living in 20th-century homes, there’s more than enough diversity to go around.