Today, a replica of the Bagley Avenue shop, built of original bricks, is part of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.

What better berth for a Tin Lizzy of the Arts & Crafts era than a pergola-garage? These pastoral structures were only one stage in the garage’s metamorphosis to its modern form.

Keeping up with the racing popularity of the automobile was a heady task at the turn of the century. Like the computer of today, what started as a technological novelty in 1893 had zoomed to a business necessity by 1918. Along with a need for paved roads, traffic controls, and sources of fuel, automobiles posed a unique architectural challenge: How to best shelter the machine? The answer was the garage, a new building type that was pronounced “part of every modern home” by 1923. A direct design descendant of carriage houses and stables, the garage—from the French word garer, the act of docking—evolved in surprising ways to meet the demands of the automobile age. Knowing a little about the garage’s rich style history can help you appreciate the building you may already have, or restore its lost character with design and materials—particularly for doors—appropriate to its period.

Carriage Carry-Overs and Simple Sheds

Compared to a horse and buggy, the early automobile—car for short—was dauntingly complex, even to dealers who at first knew little about their products. In 1913, Collier’s magazine warned that a car stored in an unheated space could end up with a frozen radiator, rattling doors, bowed fenders, a cracked frame, and flaking paint. Some kind of auto shelter seemed the only way to avoid disaster.

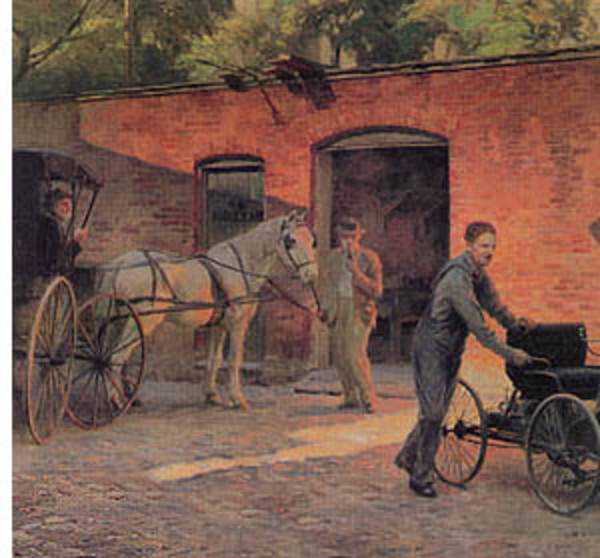

Many well-to-do car owners, the first consumers to take advantage of the new transportation toy, converted a carriage house to a garage by removing horse stalls and turning the tack room into a tool room. A country house still keeping horses for sport might hire an architect to design an elaborate stable-garage complex—preferably with separate wings. However, as the car grew to symbolize and dominate modern life, the carriage-house garage became a holdover from hay and harness days few were sorry to see go.

Beyond this, there was no clear consensus on what the “auto house” should look like or where it should be located. The first purpose-built garages disappointed almost everyone. Most were little more than overgrown woodsheds—12′ x 18′ rectangular boxes architecturally unrelated to the house. Early cars were not enclosed, so the need for shelter was crucial and immediate. Initially, these ad-hoc outbuildings occupied a humble place at the rear of the lot.

Until the early 1920s, most cars were purchased without the aid of an installment plan. A major cash outlay of $500 to $1,200 or more often left little money to pay for anything fancier than a tiny shed. The cheapest option was the portable garage built at a factory and shipped in sections. The motorist could assemble the garage himself in a few days’ time. Though flimsy, these low-cost sheds were promoted as ideal for renters who could take their garage with them if they moved.

The Garden Garage

As criticism of crude sheds mounted, designers experimented with ways to build garages in the tradition of gazebos and other garden structures. The most creative solution was the “pergola garage,” a one- or two-car shelter detailed with columns at its corners and a trellis framework across the roof. By 1914, one could buy plans for a pergola-garage promoted by the Southern Cypress Manufacturer’s Association, or a kit of ready-cut materials from mail-order house purveyors like Sears Roebuck or Aladdin. If you already had an ugly shed garage, magazines such as House Beautiful would show you how to “subdue” it with a pergola-like camouflage of vines.

Some designers suggested that a freestanding garage should be clad in cobblestone or have a pseudo-thatched roof suggestive of a gardener’s cottage. Others took the garden garage idea to its limit by burying the shelter in the side of a hill. At the very least, a simple, rectangular garage could be connected to the house with a vine-covered pergola or breezeway.

The Architectural Garage

By 1922, critics were applauding the fact that garages had “graduated beyond barns.” The problem, in their minds, was how to design a garage to “harmonize with the house.” The architectural garage, like the Victorian carriage house before it, took its cues not from the landscape, but from the house. The trick was using features bold enough to read from the street, yet simple enough to let the house dominate. A Colonial Revival garage might echo the gambrel roof and boxed cornice of the main house. The decorative half-timbering, steel casement windows, and gabled dormers of a Tudor Revival house were applied to its garage with similar medieval effect. The Spanish Revival style could be evoked in the suburbs with terra-cotta rooÞng and a curvilinear parapet, while a garage designed in the Craftsman style had a low-pitched roof and decorative rafter tails just like a bungalow.

These garages were viewed as important members of an overall “architectural composition” meant to express “artistic” qualities. When equipped with dormers to ventilate exhaust gases, some were so substantial they looked more like guest houses than garages. Many did incorporate small apartments. In fact, as one writer noted, “families often find it to their advantage to build a garage first and use it as temporary living quarters while the house is being built.”

Ironically, the architectural garage, with all its traditional connotations, was ill-suited to a zippy innovation like the automobile. Most folks of ordinary means settled for the simple box garage with a gable or hipped roof, double doors, and perhaps a stock window or two. In an era when fire was a constant fear of auto owners, many garages were built with masonry materials—ornamental concrete block, hollow tile, or just wire lath and stucco over a wood frame. Sears Roebuck and Aladdin always carried several pages of kit garages in their catalogs.

The Built-In Garage

At the same time, garage design was literally moving closer to home. As early as 1907, Harper’s Weekly remarked that “the modern automobile is wanted at the house, as a dog is wanted, as a pet.” Following this logic, why not have the garage built right into the house? Once the fear of fire had been quelled, architects began incorporating the garage inside the walls of the house either under a porch or, more commonly, in the basement. “Cottages or small houses may have a garage built underneath,” noted architect Charles W. White in 1912—a likely move on lots where space was limited. Since backing out of a tight, subterranean garage was a demanding maneuver for early drivers, some builders added a mechanical turntable in the floor to reorient the auto.

The Attached Garage Logical as the built-in garage might appear on paper, its contribution to the house was more practical than architectural. A better compromise was the attached garage—not built in, but not entirely freestanding either. Providing all the assets of a built-in without the complexities of a sloping or excavated lot, the attached garage had the much-touted advantage of increasing the apparent size of the house.

Attached garages popped up occasionally in the 1920s, but really came into full flower a decade later. The typical plan was a one-story, two-bay, gable-roofed structure appended to one side of the building. The gable could face the street to contrast with the main house, or be oriented sideways to blend with the main roof. In either version, close proximity to the kitchen door was a must for unloading groceries.

Although it shared a common wall with the house, the attached garage still ran the risk of looking like an afterthought. Some architectural styles handled this problem better than others. Colonial Revival homes, for example, could maintain their symmetry by balancing the attached garage with a sun room addition on the other side. The horizontal Ranch house was tailor-made for the attached garage. Foursquares, however, could not make peace with this modern appendage.

By the dawn of the post-War years after 1945, the attached garage was being recognized for its added value-storage. The half-story over the double bay, in close proximity to the house, became a second, unheated attic for warehousing garden implements and storm windows. In the new basement-less, slab-construction houses, the second garage bay was suggested as being an ideal space for a workshop or for drying laundry. Today, garages continue to grow in both size and prominence. The trend in many tract homes, in fact, is a three-car garage so aggressively large and street-oriented that the house fades meekly into the background. Efforts to minimize its visual impact have virtually ceased. A fresh look at the garage’s roots may help revive the architectural partnership it enjoyed with the house earlier in this century.