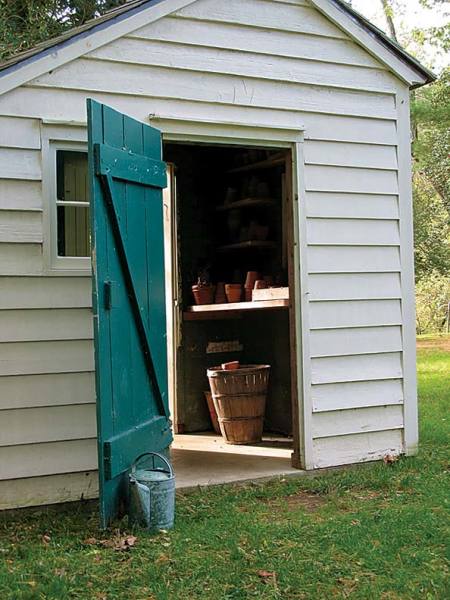

The teal door of the potting shed at Historic Walnford adds an unexpected touch of color. (Photo: Christopher Magarelli)

It was a classic case of contractor doesn’t know best: A few years ago, a carpenter who was estimating a few small repair jobs on my friends’ 1905 Folk Victorian house informed them that their old garden shed wasn’t worth saving and that the smart thing to do would be to replace it with a cheap, mass-produced utility shed.

My friends were aghast at the idea—although the shed was showing some wear and tear, it had charm and space they would never get from a pre-built shed. Today, the little shingled building, painted cream with a bright blue door and window box, provides a cheery focal point to a corner of their yard, fits right in with the architecture of the house and the surrounding neighborhood, and gives them a place to store compost, tools, and bikes.

The lesson? Though they may be tucked away in backyards, garden sheds are nevertheless major contributors to a home’s overall character. Whether you’re building new or rehabbing an existing shed, the same sense of historical integrity that governs restoration projects on your main house still applies.

Shedding Some Light

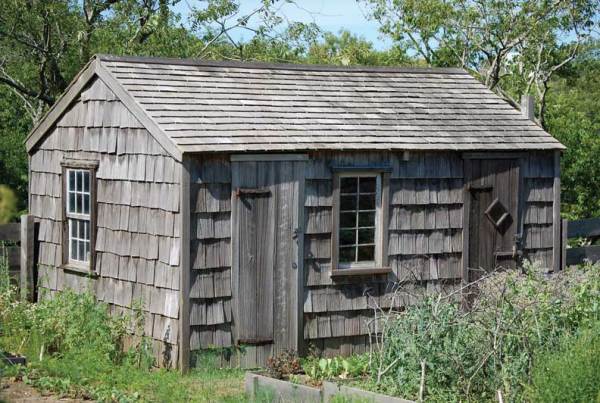

The garden shed at the Oldest House on Nantucket was constructed well after the 1686 home, but hews to its aesthetic by using weathered materials. (Photo: Curt)

“Shed,” an Old English word that dates from before the 12th century, means a slight structure built for shelter. The garden shed may well descend from the medieval herb house, which was filled with pungent aromas and shelves of medicinal tonics. In the U.S., the garden shed became an essential extension of the suburban home in the early 20th century.

Though their function may have shifted slightly, the structure of sheds hasn’t changed much over the centuries. Garden sheds still tend to be small, simple outbuildings that serve as workshops or potting areas, and provide storage space for tools and other possessions that either don’t belong or don’t fit in the house.

Like other outbuildings, sheds are typically sited behind the house, preferably in a place that can’t be seen from the street. The ideal location is one that’s convenient for use but doesn’t block the view of—or access to—the rest of the grounds. A corner of the yard generally works best to maximize these requirements.

A shed also can be a functional part of the garden layout. For instance, at York Gate, an intricately designed plantsman’s garden near Leeds, England, both the iris garden and kitchen garden end at an attractive wall punctuated by a circular window and an arched walkway. What appears to be one common wall is actually two walls separated by a walk-though potting shed.

In keeping with their focus on utility, the interiors of garden sheds traditionally have unfinished framing with at least one window to let in light. Shelving, hooks, pegboards, and bins can hold tools and supplies, and workbenches should be positioned under a window where light is best.

Shed contents will vary depending on the intended use. Avid gardeners will consider items like string, plant labels, scissors, gloves, manuals, and work clothes necessities. Inside the York Gate potting shed, light filters through the circular windows to illuminate a tableau of old hand tools displayed on an aged, unpainted wooden workbench, along with stacks of clay pots and wicker baskets. Although there’s nothing wrong with storing the odd bicycle or mower in them, garden sheds shouldn’t be mistaken for utility buildings, those metal or vinyl boxes made to contain the excesses of modern life.

Despite a fresh coat of paint, a shed at Colonial Williamsburg retains its old-fashioned look with a moss-covered roof. (Photo: Melinda Faulk)

New Life for Old Sheds

Relegated to remote corners of the yard, garden sheds tend to be subject to the “out of sight, out of mind” principle. As updated kitchens and baths come and go, the garden shed settles deeper into the ground and looks progressively more dejected until, filled with unwanted possessions, cobwebs, and mice, it becomes a place to be avoided. Too often, this is the point at which repair costs are over-emphasized; the shed’s essential character, history, and potential are overlooked; and it is torn down.

Restoring old sheds, however, is often a fairly simple project, unlike restoring old houses. Start the process with a visual examination. A sagging roof or tilting or loose frame may indicate a danger of collapse, in which case a carpenter should be called in for further assessment. If the structure is reasonably straight, true, and sturdy, though, you can proceed with determining whether the shed can be repaired or rebuilt. The traditional unfinished interior allows the structural components of wall framing, sills, and roof to be easily examined for rot, and a few jabs with a screwdriver will reveal if they have become soft. Even a person with no carpentry skills should be able to get an idea of how extensive the decay is and how much of the shed will need to be replaced to make it usable again. If you’ve determined that your shed can be repaired, see the “Shed Rehab Checklist” below get started.

Building New

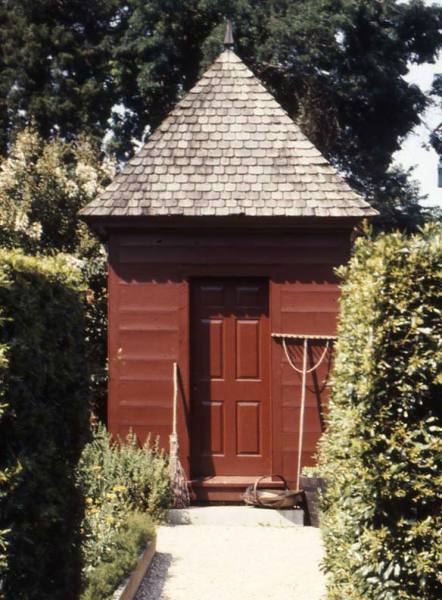

The colors on this shed, which accompanies a sunny 1720s Cape, take inspiration from the garden rather than the house. (Photo: Pamela Dyson)

If your house didn’t come with a shed, or if the one you acquired is simply too deteriorated to be rebuilt, you can still stay true to the character of your house by building a new shed in a classic style. As a general guideline, sheds should be built more simply and on a smaller scale than the house they accompany. A shed should have a footprint of at least 6′ by 6′, with a high enough roof to allow you to move around comfortably inside. While permits sometimes aren’t required for small outbuildings, you will almost certainly need one if you plan to build a larger shed. Check with your local building department before beginning to see if you’ll need a permit.

The best materials for constructing new old garden sheds are traditional ones like wood, brick, and stone—or, better still, recycled materials. When the shed is within the public view, it should adhere to, or at least honor, the architectural style and period of the house. You can achieve consistency by matching details such as the roof profile, trim, siding, and paint or stain of the house. Architectural elements found on the house (such as columns or brackets) can even be reproduced on a smaller scale for the shed.

If your shed is separated from the house visually by distance or plantings, strictly reflecting the style and age of the house isn’t as important, but it still needs to be in keeping with its surroundings. For example, a simple shed is most fitting in a rural or agricultural setting, while an in-town garden shed should be more finished and reflect the elegance of the house it accompanies.

A shed in the William Paca House garden in Annapolis, Maryland, mirrors bright blooms. (Photo: Susan E. Schnare)

While sheds aren’t subject to the same aesthetic criteria as ornamental garden structures like gazebos or pergolas, an attractive outbuilding will boost the charm of your landscape. Consider replacing siding with cedar shingles, or adding a trellis and climbing vines. (If you choose the latter, be sure to leave several inches of space between a trellis and the structure to allow air circulation and prevent rot.)

Make your shed a joy to use by getting organized before moving in. List the items that will be stored there, and put up shelves and hooks. As a finishing touch, add a doorstep, lay out a walk, and plant shrubs, flowers, or small trees to anchor the building into your garden or yard. Whether strictly utilitarian or a whimsical entity, whether newly built or on its third or fourth incarnation, the garden shed can be an attractive asset to your grounds.

Susan E. Schnare lives in a 200-year-old home and works to preserve historic landscapes through her firm, Mountain Brook Consulting.

Online exclusive: Check out our gallery of products for organizing your garden shed.