Although Sunnyside Plantation needed a major restoration, homeowner David Floyd saw its potential.

As soon as David Floyd glanced across a country road in Louisiana’s Point Coupe Parish and spotted Sunnyside Plantation’s weathered facade peeking above a field of towering weeds, he knew the 1838 Bluffland-style home—once part of a cotton plantation—would forever be part of his life.

“It was in a time capsule, a pure state of preservation. It had never been tampered with, never been modernized to any great degree,” says David, who serves as the executive director for Louisiana State University’s Rural Life Museum. “The owners had built another, more prestigious house, and this one was left alone.”

A scholar of architectural history, David immediately recognized the home’s many original 19th-century features, from vintage double-wide doors with geometrically paned transoms to Baldwin solid cast hinges and Carpenter locks. Based on the design of the home—one and a half stories with a stairwell tucked inside the wall and an equal number of rooms flanking a center hall—he was able to date it to the 1830s. It was all in pristine condition—even the cypress floors, hand-planed tongue-and-groove ceilings, and original porch columns.

“It was an architectural treasure,” David says. “As a museum director and a person who appreciates natural architecture, I wanted to own that house.”

Upon researching the home’s history, David discovered that Sunnyside had been built by Charles Tessier in 1838, who had lived there with his first wife, Laura Thomas, and their family until 1852. Sunnyside then housed the property overseer and later the adult Tessier children until 1912, when a huge flood left four feet of water inside the home. Everything survived except the plaster walls, which were replaced with cypress planks and eventually covered with wallpaper in the 1930s.

By the time David spotted the home in September 1997, it had been in the hands of another family, the Branch-Fosters, for more than 50 years. Owner Leila Branch Foster was understandably reluctant to let go of a home that carried generations of cherished memories, but after meeting David and his wife, Marla, and showing their children, Amanda and Hunter, around the house where she spent her childhood, Leila changed her mind. “Mr. Floyd, I want your children to have this home,” she told David. “The children bought the house for us,” Marla admits.

The backyard kitchen garden, like all the other gardens on the property, was designed to evoke the charm of plantation life.

The Branch-Foster family wanted to keep the property, though, so the Floyds decided to move the house. Dedicated to replicating the plantation’s original homeland, David searched for a community that would both fit the house’s historic legacy and allow the family to remain in proximity to their life in Baton Rouge. He found such a place on a 27-acre sweet potato farm bordering a 50′ bluff inside the small, historic town of Weyanoke. David recruited some colleagues equally devoted to historic architecture (including carpenter W.J. Brown and contractor Don Robert), as well as a few LSU students, to help him with the task of dismantling the home.

“You have to treat it like an artifact,” David explains. “You take it apart in such a way that the pieces go back together in the same form.”

The open kitchen was completely rebuilt after the move, but David embellished it with original details to help it blend with the rest of the structure.

Like skilled surgeons, the team meticulously removed the floors, doors, transoms, sidelights, and windows, and peeled off wallpaper (which had been destroyed by years of neglect) before popping hundreds of tacks off the cypress walls. Even the floor joists (connected by a simple lap joint) were lifted out. The rear part of the house, which comprised the kitchen and back porch, was a later addition that had experienced some rot, but the crew was able to salvage some lumber and the kitchen windows, which were original to the house.

Every piece was labeled, packaged, and thoroughly documented. Protecting this priceless jigsaw puzzle, David and the students moved all the boxes and piles of lumber. All that remained was a framed shell consisting of four beams. Two beams were cut to separate the structure into two sections, and Sunnyside was loaded onto two flatbed trailers for the four-and-a-half hour trip to its new site.

Just minutes after the home reached the site on a December afternoon in 1997, it began to rain, and didn’t let up for nearly three months. David and his helpers slipped a railroad jack beneath the trailers and tilted the shell of the building to help drain the water. They kept it like that until the first week of March, sidestepping major damage. However, the foul weather continued to postpone the restoration work. “At one point, I had a broom in one hand and a bourbon in the other, constantly pushing the water out the door,” David says.

In the master bedroom, an American Empire four-poster bed is surrounded by cherished mementos.

After the weather finally cleared, the house was put back together the same way it had been taken apart. While most of the original house remained intact, the kitchen and rear wing of the house had to be completely reproduced. David carefully replicated baseboards, window frames, and millwork from examples found elsewhere in the house (all cut with knives custom-made for the project), resulting in a seamless blend. “Since the window sash is original, many people believe the kitchen is original,” he explains. Modern kitchen appliances, as well as central air/heat and satellite television, also were added, but David notes these new amenities can be removed easily. Less than a year after the move, on Labor Day weekend 1998, the Floyd family settled into their home.

Original mantels and millwork join deep-pitted wood-burning fireplaces inside the two parlors flanking the main foyer. One parlor, highlighted in silk drapes and antique furnishings, is dedicated to more formal entertaining, while the other holds a collage of comfortable furniture, along with a veritable museum of family heirlooms and rustic long-barreled rifles. The sense of history continues in the master bedroom, where an American Empire four-poster bed covered in an ivory silk comforter holds company with a closet filled with period clothing.

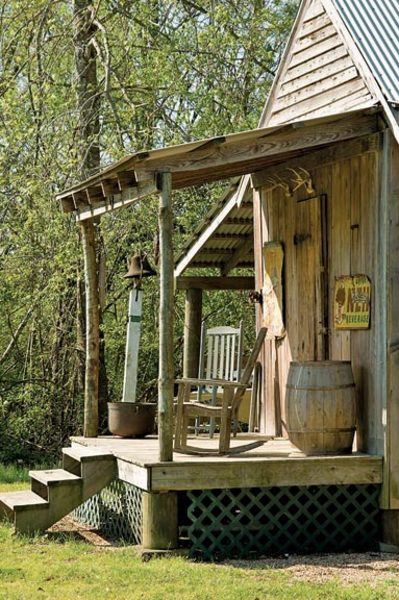

The property’s collection of outbuildings includes a general store-style barn.

The second floor overlooks the flower-filled parterre that fronts the home and the backyard vegetable garden. Eighteenth- and 19th-century gardens are David’s area of expertise, and he designed his own landscape to emulate the romance and charm of plantation life, adding a few period outbuildings—including a general store-style barn and a pigeonnier—to the mix. Beyond the formal gardens, a small grove of pecan trees and a tunnel of flowering crape myrtles offer dappled shade, while hanging bottles and gourds sway in the breeze to guard against owls, crows, and chicken hawks.

Ever mindful of future stewards of the home, David kept meticulous records of Sunnyside’s restoration, including samples of the original and reproduction millwork. As the director of a historic museum, who sits on historical boards and oversees high-profile restorations throughout Louisiana, he gains great satisfaction in having preserved the historical integrity of the building.

“We don’t own homes; we’re only caretakers of them,” David explains. “And I’m just trying to be a good caretaker.”