Part of a group of picturesque Spanish Colonial Revival houses of the 1920s in Coronado, California, this house displays the rambling, asymmetrical massing and prominent chimneys of its style, all unified by white stucco walls and a red barrel-tiled roof.

American houses have generally reflected a strong bias toward English-inspired styles—Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, or Arts & Crafts, for instance. During the late 19th- and early-20th centuries, however, builders in parts of the country with a Spanish heritage began to follow quite a different vision—or, to be more precise, several different visions. Influenced by the Arts & Crafts movement, with its emphasis on simplicity, vernacular building practices, and regional history, architects in Florida, the southwestern states, and California began to produce distinctive designs based on examples from each region’s particular Spanish past.

The first flurry of national interest in Spanish architecture and heritage appeared at the end of the 19th century in the wake of some early examples, such as Carrere and Hastings’ 1888 Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine, Florida, and the Mission Style California Building at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition by San Francisco architect A. Page Brown. However, it was only in 1915, when the Panama California Exposition in San Diego showcased Bertram Goodhue’s stunning Spanish Revival designs that the Spanish craze began in earnest.

The interest in Spanish Revival architecture intensified during the period between the two World Wars, finally petering out around 1940. While the earlier revivals were built mostly in Spanish-settled areas, the later ones (though they often continued to have regional flavor) popped up all over the country. Furthermore, while early revivals were rather free adaptations of the originals, later revivals of, say, the 1920s were likely to be truer to the historical styles, at least in architect-designed buildings.

The 1909 Gerson House in Oklahoma City, with its arcaded porch, stuccoed walls, barrel-tile roof, and curved dormers, is a good early example of the Mission Revival style.

These regional differences, as well as changing architectural tastes over 50 years, left the landscape with a number of very different “Spanish” styles. These include the Mission (or Mission Revival), Spanish Colonial Revival, Pueblo Revival, Territorial, and Monterey styles. To that list we might add the Mediterranean Style, which is a blend of rustic Italian and Spanish Renaissance styles. In fact, all the Spanish revival styles are sometimes lumped under the Mediterranean label. Taking them more or less in chronological order, here’s a rundown of the most salient characteristics of the styles.

Mission Revival

This refined example of the Mission Revival is in Lexington, Virginia. It is notable for the “shaped,” or curved, gables over the porch and dormer.

The first widespread use of Spanish motifs was developed from the white-stuccoed churches that dotted the California landscape during the Spanish settlement period of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Spanish missions provided the general inspiration for these picturesque structures with smooth, flat wall surfaces, shadowy arcaded promenades, and curvaceous gables. Their most conspicuous features were most often their shapely, scalloped parapets with heavily molded edges, which might adorn not just the main roof but one or more dormer and porches as well. They had low-pitched barrel-tile roofs, generally with widely overhanging eaves.

Ornamentation was typically of terracotta and was often vaguely Moorish in design. Quatrefoil windows and cartouches appeared regularly. Windows and doors in myriad arch shapes, from Moorish to flattened semicircles, were also often edged with heavy mouldings of stone, brick, or terracotta. Bell towers, frequently in pairs, were common. Domes were less frequent. All these details fit nicely within the Arts & Crafts movement’s tendency to stress indigenous architectural forms and at the same time presaged the eclectic European architectural revivals that would prevail in the 1920s and ’30s. Irving Gill, the California architect who would become famous for his cubic Modern buildings, experimented first with the Mission Style’s simple lines. After World War I, architects and builders abandoned Mission Style buildings in favor of more academic European architectural revivals—though not before a lot of lovable little Mission bungalows and cottages with pseudo-stucco walls had left their mark on suburban developments all over America.

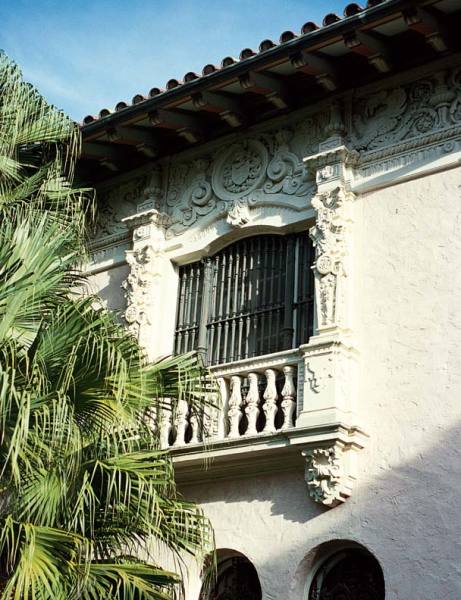

The intricate Spanish Renaissance ornament known as churringueresque is found in the best Spanish Revival houses in window and door details, as in this Coconut Grove, Florida, example.

Spanish Colonial Revival

Architect Bertram Goodhue began the trend toward Spanish Colonial buildings that were more formal and historically accurate representations of the Spanish Renaissance. George Washington Smith, Montecito, California, architect and author of an early, groundbreaking book on Spanish architecture in the American West, is considered the most talented practitioner of Spanish Colonial in Southern California.

Spanish Colonial was the most decorative of the Spanish styles, and its ornament covered a wide range of source material, from Moorish to Renaissance and Byzantine. With hipped or gabled red-tile roofs, Spanish Colonial homes often featured twisted, spiral columns beside door and window openings, with heavy, carved doors and decorative tile trim. The intricate ornamental forms of Old World Spanish buildings, called Churrigueresque ornament, were a hallmark of high-style Spanish Colonial homes. In Coral Gables, Florida, architects Kiehnel and Elliott designed a gorgeous winter residence, El Jardin (1917), for a president of Pittsburgh Steel using such ornament. However, the Spanish Colonial home was not all glitz and glamour, for it extended—in simpler forms—to ordinary suburban buildings as well in every part of the nation.

Pueblo Revival

The Pueblo Revival is a 20th-century adaptation of a building type developed in the late-18th and early-19th centuries in New Mexico’s Rio Grande Valley. It was, and still is, extremely popular in Spanish-settled areas of the Southwest, particularly New Mexico and Arizona.

The Pueblo Revival employs thick walls made of real or fake adobe, with soft, slightly rounded wall edges and a smooth stucco finish mimicking the original mud finish. (Real adobe is air-dried mud bricks covered with more dried mud; adobe-looking substitutes might be concrete blocks or even wood-framed structures covered with smooth, colored stucco.) The key words in the Pueblo Revival vocabulary are “small” and “simple,” and these earthy houses are low and ground-hugging, almost always a single story high. When there is more than one story, however, the higher ones are usually designed in a setback to look like the originals.

A traditional Spanish house in Albuquerque sports an unusual Pueblo-style bay window, replete with vigas—projecting round beams used in traditional Pueblo work.

Heavy wood vigas (roof beams) that may be real or fake are embedded in the walls and project through the exterior surfaces. The roofs are flat, hidden behind parapets. In the authentic pueblo dwellings still to be seen in Native American villages of the Southwest, canales (hollow logs) carried the infrequent rain water away from the flat, earthen roofs. Portales (porches) often opened off an interior patio, taking the place of interior corridors to provide access to the various rooms. Front doors might be heavily paneled or constructed of vertical boards. Windows are generally small and few, and are more often casements rather than double-hung sash.

Pueblo Revival is now the officially required building style for new structures in the historic area of Santa Fe, and is routinely used in new construction outside the historic area as well—which has resulted in at least one gigantic “adobe”-canopied gas station.

Interior features include plaster walls (again resembling smooth stucco) and corner fireplaces of adobe-like material. Brick terraces and patios are common outside amenities. Prominent architects who worked in the Pueblo Revival Style include John Gaw Meem, perhaps the best known of the lot; and Mary Jane Coulter, the architect for the Santa Fe Railroad and the railroad’s affiliated Fred Harvey restaurants. In fact, the popularity of the Pueblo Revival style—and New Mexico’s economy—received a big boost after World War I when the railroad instituted a highly successful tourism program that brought thousands of souvenir-buying eastern visitors to the Indian markets on breaks in their transcontinental trip.

Territorial and Monterey Revival

The Monterey style’s primary feature is a second-floor porch across the front of the house, recalling an early tradition in Monterey, California. This house in Pasadena also features an unusual, unadorned pointed-arch doorway.

New Mexico builders of the 19th century often chose houses in the Territorial style. The name, of course, refers to the days when New Mexico was a U. S. territory. Architecturally, the Territorial style is a slightly easternized version of the Pueblo. This rectilinear building type features adobe walls, double-hung window sash, and flat or low-gable roofs edged with a brick frieze.

In California, the Monterey style also blended old Spanish building characteristics with those of eastern houses of the same period. The Monterey Revival, a minor 20th-century version of an earlier style, featured projecting balconies on the front of the second floor.

Some cities took their Spanish architectural heritage so much to heart that they regulated new building to ensure that Spanish traditions would prevail. For example, after an earthquake destroyed downtown Santa Barbara, California in 1925, the city set up a planning commission and architectural review board for that purpose; even today new buildings are Spanish in design. Santa Fe, New Mexico, adopted a similar approach, requiring new buildings in its historic area to be in Pueblo Style.

The Territorial style takes its name from New Mexico’s time as a U.S. territory. It combines the Pueblo style with Anglo features, particularly brick cornices, as seen in this Albuquerque house.

A major aspect of the Spanish styles, like all the Romantic Revival styles, was the imaginative use of the landscape to extend and enhance the buildings. In the 1920s and 1930s an army of talented landscape architects such as Olmsted and Olmsted, Lloyd Wright, and Florence Yoch created near-magical settings for the homes of the wealthy in every style.

From its beginnings in Florida, California, and the Southwest, the Spanish craze swept across the nation like a tumbleweed, propelled by the efforts of stellar architects, middle-class suburban merchant-builders, and even catalog-house companies like Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward. Though it faded away in most parts of the country with the onslaught of the postwar ranch house and the split-level, to this day it holds its own in the places where it made the most sense to begin with: the Hispanic areas where it was born.